6 Minutes

New high-pressure experiments suggest Earth’s inner core isn’t a typical solid but a hybrid, superionic material: iron remains crystalline while light elements such as carbon flow through it like a liquid. This unexpected behavior offers a neat solution to seismic puzzles that have challenged geoscientists for decades.

Earth’s inner core may not be a conventional solid at all, but a superionic material where light elements drift like liquid through a rigid iron lattice. New experiments show that this unusual state dramatically softens the core, matching seismic clues that have puzzled scientists for decades.

A different kind of solid: what is superionic matter?

Most of us think of solids as rigid and immobile at the atomic scale. Superionic materials break that intuition. In a superionic phase, one sublattice—typically made of heavy atoms like iron—retains long-range crystalline order, while lighter atoms move freely through interstitial spaces, acting more like a fluid. The result: a single material that is simultaneously solid and liquid-like in different respects.

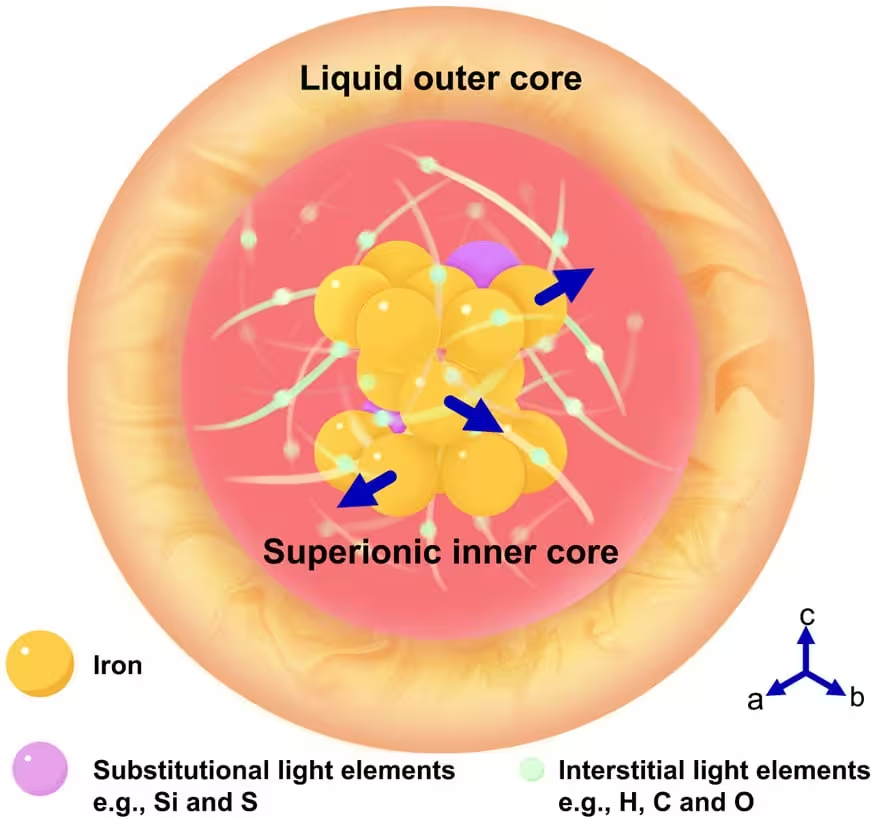

Applied to Earth's inner core, that means a hexagonal close-packed iron framework can remain ordered, while carbon atoms diffuse rapidly between lattice sites. The mechanical effect is striking: shear resistance drops, seismic shear waves slow, and the effective Poisson’s ratio increases—properties that seismologists have long observed but struggled to explain with conventional alloys or pure iron models.

Recreating core conditions: the shock compression experiment

Researchers led by Prof. Youjun Zhang and Dr. Yuqian Huang (Sichuan University) together with Prof. Yu He (Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences) used a dynamic shock compression platform to push iron–carbon samples into the same extreme pressures and temperatures found at Earth’s center. Samples were accelerated to roughly 7 kilometers per second, producing peak pressures near 140 gigapascals and temperatures approaching 2,600 kelvin—conditions comparable to the inner core.

How they measured the effect

While subjecting samples to these transient but intense conditions, the team combined in-situ sound velocity measurements with molecular dynamics simulations. The experimental data showed a pronounced drop in shear-wave velocity and a jump in Poisson’s ratio—precisely the seismic signatures observed in deep-Earth studies. At the atomic level, simulations and analyses indicated carbon atoms diffusing with liquid-like mobility inside an intact iron lattice.

Iron atoms form a rigid hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure, with a subset of these atoms exhibiting collective motion along the [100] and [010] directions. Within this hcp iron lattice, interstitial light elements diffuse freely in a liquid-like manner, while substitutional light elements remain confined to their respective substitutional lattice sites. Consequently, the Earth’s inner core exists in a hybrid state of solid and liquid-like behavior. Credit: Huang et al.

Why this matters for seismology and the geodynamo

Seismologists have observed that the inner core transmits shear waves more slowly than expected for a dense iron metal; its Poisson’s ratio is anomalously high—closer to soft metals or even plastics than to rigid steel. The superionic model accounts for both phenomena: mobile carbon lowers shear rigidity without destroying the iron’s crystalline order, producing the precise mechanical fingerprint recorded by seismic networks.

Beyond seismic properties, mobile light elements could drive or modulate internal processes. The diffusion of carbon and other light species may contribute to chemical transport, feed into anisotropy (direction-dependent seismic speeds) and even provide additional, previously unaccounted-for energy for the geodynamo—the mechanism that sustains Earth’s magnetic field. Dr. Huang notes that atomic-scale motion inside the inner core represents a subtle but potentially important energy reservoir for planetary magnetic activity.

Broader consequences: planetary interiors and materials science

The discovery reshapes how we model planetary interiors. If interstitial light elements create superionic phases under extreme pressure and temperature, similar behavior could occur inside other rocky planets and large exoplanets, with consequences for their thermal histories, magnetic fields, and seismic signatures. For materials science, the experiments showcase how extreme-condition techniques can reveal unexpected matter states and point to new classes of high-pressure materials with mixed transport properties.

Expert Insight

“This work gives us a tangible mechanism to reconcile seismic observations with core chemistry,” says a fictional planetary physicist Dr. Elena Morrison, who was not involved in the study. “The idea that carbon can behave like a fast-moving fluid while iron stays crystalline forces us to rethink inner-core dynamics—and to revisit magnetic-field models that depended on more conservative assumptions.”

Prof. Zhang summarized the significance succinctly: “For the first time, we’ve experimentally shown that iron–carbon alloy under inner core conditions exhibits a remarkably low shear velocity. Carbon atoms become highly mobile, diffusing through the crystalline iron framework like children weaving through a square dance, while the iron itself remains solid and ordered.”

Looking ahead, follow-up work will examine other light elements—oxygen, sulfur, silicon—and explore how mixed interstitial-substitutional chemistries affect superionic behavior. Improved seismic inversions, extended high-pressure experiments, and refined computational models will be necessary to map the inner core’s composition and dynamics more precisely.

Discovering superionic behavior in Earth’s innermost region is more than a niche mineralogical result. It connects laboratory physics, seismology, planetary magnetism, and materials science, offering a unified explanation for anomalies that have persisted for decades—and pointing to new directions in the study of planetary interiors.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Reza

Wow didnt expect carbon to act like a liquid inside solid iron, that image stuck in my head. If true, planetary models need a big rewrite! curious about O and S next

atomwave

Is this even true? Shock compression runs are so brief, can they mimic lifetimes and slow processes in the core? sounds neat, but I wanna see repeated tests and other elements

Leave a Comment