5 Minutes

Scientists are experimenting with a provocative idea: using living human brain cells as computing hardware. These so-called biocomputers — networks of stem-cell-derived neurons grown on electrodes — can already do simple tasks such as playing Pong or recognising basic speech patterns. But the technology is nascent, and its rise raises scientific opportunities and urgent ethical questions.

What are biocomputers and how do they work?

For decades, neuroscientists have cultured neurons on microelectrode arrays to study electrical signalling. That groundwork led to two intersecting advances that now underpin biocomputing efforts.

First, the development of brain organoids — three-dimensional clusters of neural tissue grown from stem cells — gave researchers a way to produce human-like neural networks in vitro. Second, improved microelectrode arrays and closed-loop systems allow two-way communication between living tissue and electronics. Combined, these techniques create a biohybrid platform where living neurons send and receive electrical signals to computerised controllers.

From lab benches to simple games

In 2022, researchers demonstrated cultured neurons learning to play Pong inside a closed-loop system. The experiment showed that a sheet of neurons could adaptively modify firing patterns in response to feedback — a milestone that drew big headlines. But the actual capabilities of those systems remain limited: they show adaptive responses rather than anything resembling human-like cognition.

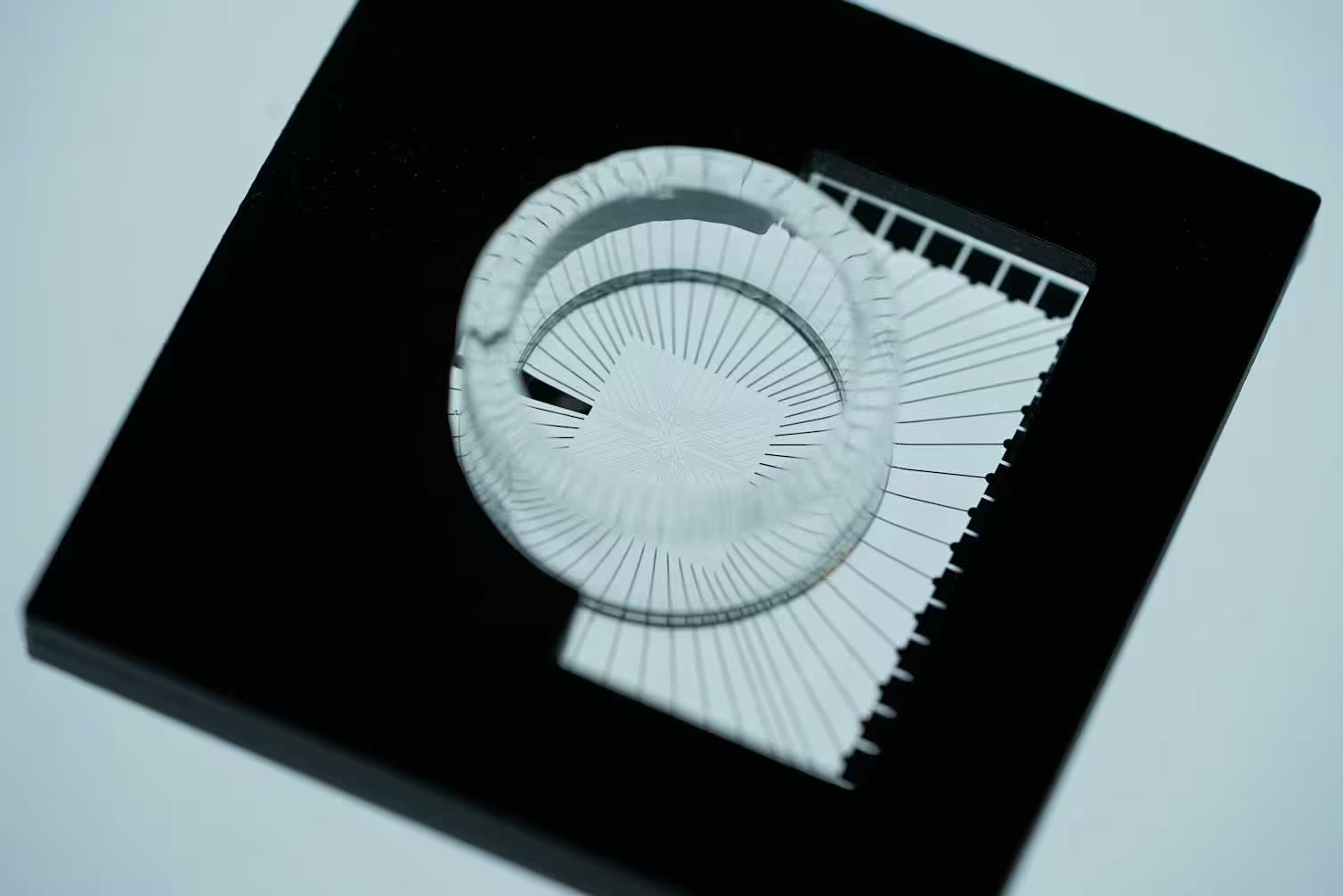

A newly fabricated microelectrode array

Why the field is accelerating now

Three converging trends have pushed organoid-based computing into the spotlight.

- Investment: Venture capitalists are pouring money into projects adjacent to artificial intelligence, making speculative bets on unconventional hardware more viable.

- Biotech maturation: Techniques for growing and sustaining neural tissue outside the body have matured, and the pharmaceutical industry now uses organoids routinely for drug screening and developmental studies.

- Interface advances: Progress in brain–computer interfaces and microelectronics blurs the line between biological tissue and engineered systems, making hybrid designs more practical.

These drivers have encouraged startups and university labs in the United States, Australia, Switzerland and China to build prototype biohybrid platforms. Some companies already offer remote access to neural organoids, and others are preparing desktop devices intended for research use.

What organoid intelligence actually means

Researchers coined terms like "organoid intelligence" and "embodied sentience" in ways that grabbed media attention but also sparked controversy. Those phrases can imply parity with software-based AI, which is misleading. Current organoids are far from the organised, large-scale network dynamics associated with human cognition or consciousness. Most experts emphasise that present-day organoids show primitive electrical activity and basic adaptive behaviour — not awareness.

Still, the label matters. Language shapes public perception and policy. When companies market living neural tissue as a new kind of intelligence, they risk outpacing ethical frameworks designed for organoids as biomedical tools rather than as computing components.

Potential uses and realistic expectations

At present, practical applications are incremental and research-focused. Promising near-term uses include:

- Improved models for neurodevelopmental toxicity tests, reducing reliance on animal experiments.

- Hybrid systems to probe epilepsy-related dynamics and assess seizure risk using human neurons combined with electronics.

- Experimental computing platforms that explore alternative information-processing paradigms rather than replace silicon for mainstream AI workloads.

Ambitious proposals also exist. Some academic teams suggest using organoid-based systems for specialised simulation tasks — for example, predicting environmental patterns or complex trajectories — though such applications remain speculative and face steep technical hurdles in reproducibility and scaling.

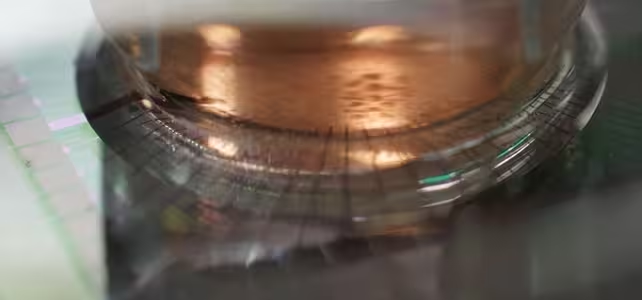

A microelectrode array covered with neurons

Ethical and governance challenges

Biohybrid computing raises questions that reach beyond lab technique. Key concerns include:

- Consciousness thresholds: How would we know if a cultured neural network attained properties warranting moral consideration?

- Consent and tissue sourcing: What rights do tissue donors have, and how should consent forms account for computing or commercial uses?

- Regulatory gaps: Existing bioethics guidelines focus on organoids for medical research, not for commercialised computing platforms — an area where governance is lagging research and investment.

Leading organoid scientists have called for urgent updates to ethics guidance to address commercialisation paths and the novel behaviours of biohybrid systems. Public discussion is limited, yet the technology’s trajectory suggests these debates will become pressing sooner rather than later.

Where the technology could go next

Technically, the path forward depends on reproducibility, scale and integration. Researchers must reliably produce tissue with consistent activity, connect multiple modules without losing function, and define standard benchmarks for performance. If those challenges are addressed, organoid systems could become niche experimental tools that complement — but do not replace — conventional computing.

Equally important are societal choices: how much we invest, how transparently experiments are communicated, and what regulatory safeguards we accept. The interplay of funding, hype, and ethics will shape whether biocomputers become a scientific breakthrough, a commercial curiosity, or a governance headache.

Expert Insight

"We should treat these systems with both excitement and caution," says Dr. Elena Márquez, a neuroengineer and science communicator. "From a technical perspective, organoids offer novel ways to study human neural dynamics in vitro. But from an ethical and policy perspective, we must update consent procedures and oversight now, not after commercial products appear. Clear standards will protect donors, researchers, and the public."

That sentiment reflects a common view among researchers: progress is real but incremental, and societal debate needs to move at least as fast as the labs and startups chasing the next milestone.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

datapulse

Interesting tech, but calling organoids 'intelligence' feels like hype. Needs clearer rules and donor consent, reproducibility matters — curious to see real results

bioNix

wait, are we actually culturing bits of brain to run games? this reads like sci fi and the consent/ethics part feels murky... who watches this stuff?

Leave a Comment