4 Minutes

Engineers at Cornell University have developed a textile that soaks up nearly all light—99.87% of it—creating one of the darkest fabrics on record. The discovery blends biomimicry, polymer chemistry and nanoscale surface engineering to produce an ultrablack merino wool suitable for fashion and functional uses.

How researchers turned wool into an ultrablack material

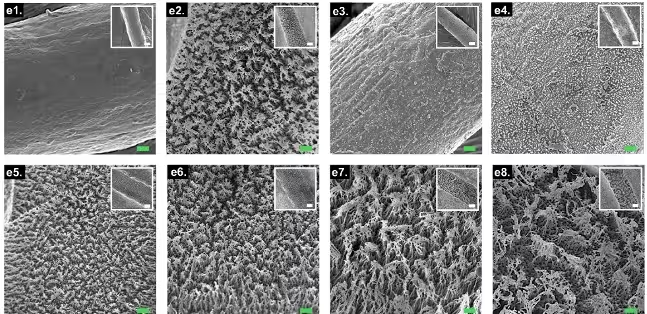

Making something “ultrablack” is not a matter of stronger dye. Instead, the Cornell team changed how the fabric interacts with light at the nanoscopic level. They started with white merino knit and soaked it in a synthetic melanin polymer called polydopamine. That layer darkened the fibers chemically, but the key step was structural: the fabric entered a plasma etching chamber where researchers sculpted nanofibrils—microscopic hair-like ridges—across the fiber surfaces.

A dress designed by Zoe Alvarez, inspired by the magnificent riflebird, partly made with the blackest fabric on record (the dark black border around the blue).

Those tiny fibrils trap incoming photons. As Hansadi Jayamaha, a fiber scientist and designer involved in the work, explained, "The light basically bounces back and forth between the fibrils, instead of reflecting back out—that's what creates the ultrablack effect." The repeated internal scattering effectively removes most reflected light, producing the dramatic low-reflectance appearance.

Images showing the microscopic structure of untreated white merino wool (e1) and dyed, plasma-treated wool (e5-8).

Nature as a blueprint: the magnificent riflebird

The team borrowed inspiration from the magnificent riflebird (Ptiloris magnificus), a bird from New Guinea and northern Australia celebrated for iridescent blue-green chests framed by near-black plumage. In the bird, feather microstructure suppresses scattered light and enhances the visual contrast. Cornell’s fabric mimics that microstructural trick—but with improved angular performance: the riflebird’s black is darkest when viewed straight on and becomes more reflective at steep angles, while the engineered textile maintains its low reflectance up to about 60 degrees either side.

.avif)

A male magnificent riflebird

Where this fits among ultrablack technologies

The new wool is not the absolute darkest material known—Vantablack famously absorbs about 99.96% of incident light, and a later MIT carbon nanotube array reportedly reached 99.995% absorption. But those high-performing materials can be costly, limited to rigid substrates, or difficult to scale. Cornell’s approach uses inexpensive merino wool and scalable chemical and plasma processes, which the researchers say could be adapted for larger-scale textile production.

The team also demonstrated practical uses: fashion design student Zoe Alvarez created a gradually darkening dress that culminates in the ultrablack border surrounding a vivid blue-green center, echoing the riflebird’s plumage. That piece shows the material can be integrated into garments and visual designs, not just lab samples.

Applications and implications

Beyond fashion, ultrablack textiles have potential in optical sensors, thermal management, and theatrical or display industries where controlling stray light is critical. Materials that trap light efficiently can also improve instrument sensitivity in scientific cameras or reduce glare in architectural finishes. Because the process uses accessible polymers and plasma etching, the pathway toward industrial use looks promising—though durability, washability and large-scale manufacturing logistics will need focused testing.

While the study—published in Nature Communications—does not claim the ultimate black, it demonstrates a practical route to near-total light absorption on flexible, wearable fibers. For designers, engineers and instrument builders, that opens a new palette of ultra-low-reflectance materials that are easier to produce than many earlier ultrablack technologies.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment