5 Minutes

Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers have identified microscopic nanotube channels between neurons that can transport toxic molecules — a discovery that adds a previously unrecognized layer to brain connectivity and may help explain how Alzheimer’s pathology spreads. Using high-resolution imaging in mice and human electron microscopy datasets, the team observed long, slender dendritic nanotubes shuttling amyloid-beta and other small toxins between cells, suggesting a new target for future therapies.

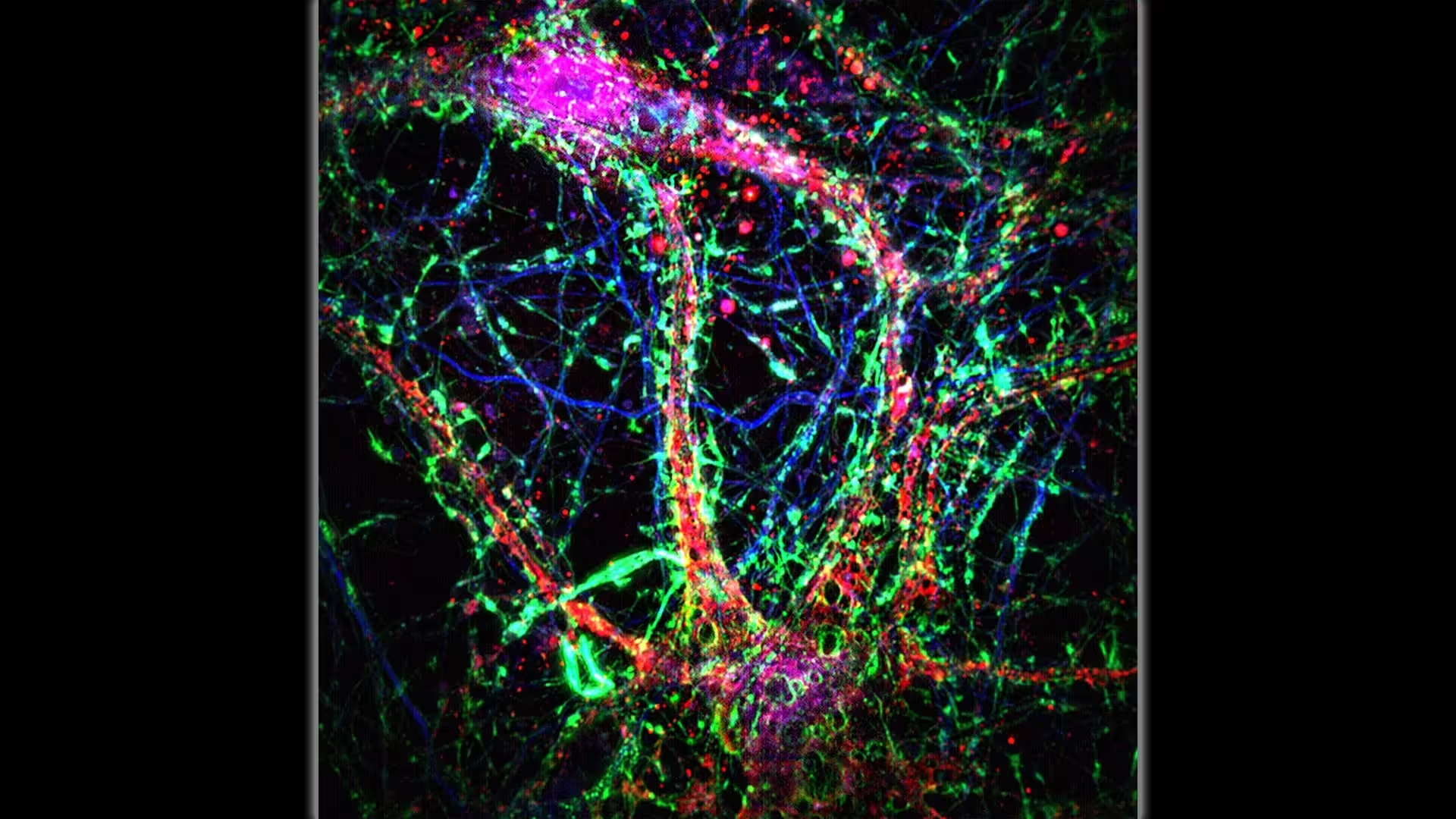

Scientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine say intercellular nanotubes (thin, green-dominant, bridge-like connections) contribute to an additional layer of communication within the neuronal network. Credit: Minhyeok Chang, Ph.D.

What the team found and why it matters

Imagine neurons not only talking through synapses but also sending tiny parcels through tubular bridges. That’s the basic picture emerging from a study published in Science on Oct. 2, in which investigators described a "nanotubular connectivity layer" in the mammalian brain. These nanotubes — extremely thin membranous channels connecting dendrites of neighboring neurons — appear to move ions, calcium, and small toxic molecules like amyloid-beta from cell to cell.

"Cells have to get rid of toxic molecules, and by producing a nanotube, they can then transmit this toxic molecule to a neighbor cell," said Hyungbae Kwon, associate professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and corresponding author on the paper. "Unfortunately, this also results in spreading harmful proteins to other areas of the brain."

The dual nature of nanotubes — a mechanism for waste clearance that can simultaneously propagate toxic cargo — gives neuroscientists a new framework for understanding early-stage neurodegeneration. Computer simulations run by the team mirrored patterns of early amyloid accumulation observed in Alzheimer's-model mice, reinforcing the idea that nanotube-mediated transfer could accelerate local seeding of pathological proteins.

How the discovery was made: methods and evidence

The researchers combined genetic mouse models predisposed to amyloid buildup with live-cell, high-resolution microscopy to visualize nanotube formation in brain slices. They captured long, column-like extensions spanning dendrites and directly tracked the movement of fluorescently labeled molecules through these conduits. To validate relevance for humans, they inspected publicly available human electron microscopy datasets and found nanotubes with comparable morphology linking human neurons.

In mice programmed to develop Alzheimer’s-like amyloid plaques, nanotube numbers were elevated at three months of age — a period when the animals show no outward symptoms. By six months, when plaque pathology becomes more pronounced, nanotube counts between transgenic and control mice converged. These temporal dynamics hint that nanotube proliferation may be most active during early, pre-symptomatic phases of disease.

Supporting team and funding

The project was led by Kwon with contributions from Minhyeok Chang, Sarah Krüssel, Juhyun Kim, Daniel Lee, Alec Merodio and Jaeyoung Kwon at Johns Hopkins, and collaborators Laxmi Kumar Parajuli and Shigeo Okabe at the University of Tokyo. Funding came from the National Institutes of Health (DP1MH119428 and R01NS138176).

Implications for Alzheimer’s research and potential therapies

These findings open several translational avenues. If dendritic nanotubes are a route for amyloid-beta spread, then modulating their formation — either suppressing them to limit propagation or enhancing them transiently to improve toxic-molecule clearance — could become a therapeutic strategy. Kwon and colleagues propose future experiments to deliberately create or block nanotubes, testing how manipulation affects neuronal health, protein aggregation and cognitive outcomes in animal models.

Beyond Alzheimer’s, nanotube networks may play roles in other neurodegenerative diseases where misfolded proteins spread from cell to cell, such as Parkinson’s or ALS. The structural and functional characteristics of these nanotubes — their length, diameter, and selectivity for particular molecular cargo — will be crucial details for drug developers and neuroscientists aiming to intervene.

Expert Insight

"This discovery adds a new layer to our map of neuronal communication," said Dr. Elena Vargas, a fictive neurobiologist and science communicator with a background in protein aggregation studies. "It reframes how we think about cellular waste disposal and the unintended consequences of those mechanisms. Targeting nanotube dynamics could be a clever way to intervene early in disease progression, but we need careful studies to avoid disrupting beneficial clearance pathways."

Next steps for the Johns Hopkins team include mapping nanotube networks across different brain cell types, engineering controlled nanotube formation in vitro, and testing whether altering nanotube frequency changes the course of amyloidosis in vivo. If successful, those lines of research could point to drug targets or engineered biologics that selectively modulate intercellular nanotube activity.

For now, the discovery reframes early Alzheimer's pathology: not just as localized plaque formation, but as a dynamic process influenced by microscopic conduits that link neuronal communities. That new perspective may reshape how researchers search for biomarkers and design early interventions to slow or stop disease spread.

Source: sciencedaily

Comments

DaRex

Whoa tiny bridges moving toxic stuff between neurons? 🤯 If true this could flip how we fight Alzheimer's, hope they can block the bad transfer without killing normal cleanup, fingers crossed

bioNex

Wait, how sure are they? Could those nanotubes be a slicing artifact... imaging in mice + human EM is neat but there might be confounds, right? curious tho

Leave a Comment