8 Minutes

New multidisciplinary research suggests a powerful volcanic eruption half a world away may have set into motion the climate and trade disruptions that allowed the Black Death to sweep across Europe in the 1340s. By combining ice-core chemistry, tree-ring climate records and contemporary accounts, scientists have reconstructed a chain of events that links an unidentified tropical eruption around 1345 to famine, shifted grain shipments and the maritime spread of Yersinia pestis.

Reconstructing a catastrophe: how scientists followed the clues

Imagine reading the planet's diary: thin layers of ice and rings inside trees quietly recording weather extremes, atmospheric chemistry and crop stress. Researchers Martin Bauch and Ulf Büntgen took that diary seriously. They examined polar ice-core sulfate records, annual tree-ring growth from eight European regions and dozens of 14th-century written reports to test a provocative idea — that a major volcanic blast created a short-lived climate shock that altered trade patterns and unintentionally carried plague into Europe.

One early piece of the puzzle is the bacterium itself. Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, spreads primarily through fleas and can cause bubonic infections that move quickly in vulnerable populations. A modern-way to picture the pathogen is a scanning electron microscopy image, which shows what the bacterium looks like under extreme magnification. A scanning electron microscopy image of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for plague. (Callista Images/Getty Images)

But pathogens don’t move independently — people, goods and ecological conditions dictate their routes. That realization prompted the team to follow physical climate markers and economic responses rather than relying solely on epidemiological models.

Ice-core sulfur spikes and the cooling signature

Polar ice cores act as frozen archives of atmospheric composition. The researchers found a particularly large sulfate spike in layers dated to snow deposited around 1345 CE — a fingerprint typically associated with a major volcanic eruption. The 1345 spike stands out: it ranks among the larger sulfur insertions in the last two millennia, while smaller peaks appear in 1329, 1336 and 1341.

When volcanoes eject sulfur-rich gases into the stratosphere, those gases form sulfate aerosols that reflect incoming sunlight. The result is a measurable drop in surface temperatures for several years. Tree-ring reconstructions of temperature, which use latewood density and width to estimate growing-season warmth, show unusually cool summers across much of southern Europe from 1345 through 1347 — a classic volcanic cooling signal that aligns tightly with the ice-core timing.

The climate anomaly had immediate consequences for agriculture: reported crop failures, soggy harvest seasons and higher grain prices appear in chronicles from Spain to the Levant. Those conditions are exactly the sort that would compel commercial maritime powers to seek new sources of staple food.

A scanning electron microscopy image of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for plague.

How trade rerouting helped the plague travel

Here the human story enters: medieval Italy relied on grain imports to avoid famine. The unusually cold, wet summers and poor harvests pushed maritime republics — notably Venice, Genoa and Pisa — to reopen trade with the Black Sea region and source grain from the Mongol-controlled areas around the Sea of Azov. In 1347 Venice lifted a long-standing embargo on the Golden Horde and large shipments of grain began arriving from ports north of the Black Sea.

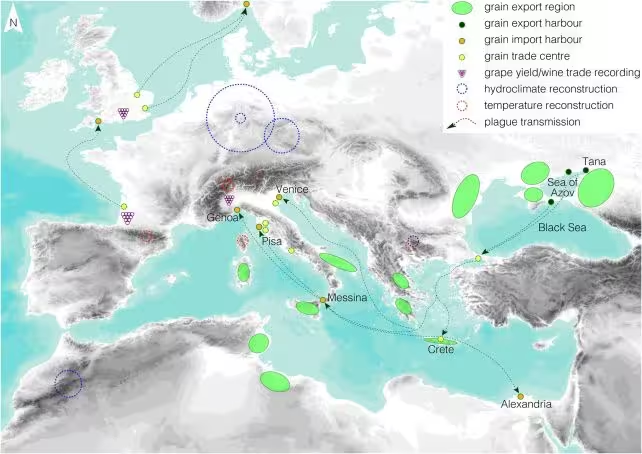

Those voyages were a plausible vector for Y. pestis. Previous research shows fleas infected with plague can survive aboard ships carrying grain and other dry cargos long enough to reach Mediterranean ports. The first documented outbreaks on European soil coincided with landings at coastal hubs: Messina, Genoa, Venice, Pisa and Palma. From those ports, the infected grain and human contact supplied the routes for the pathogen to move inland and along coastal trading networks, eventually reaching Alexandria and then northward into the English Channel and the North Sea.

A map of the grain shipment plague vectors of the late 1340s. (Bauch & Büntgen, Commun. Earth Environ., 2025)

Why this interpretation matters for understanding pandemics

Was the Black Death a homegrown European recurrence or did it arrive anew from Central Asia? This new study supports a reintroduction hypothesis: recent genetic and archaeological data place the emergence of the second pandemic in Kyrgyzstan and neighboring highlands. The volcanic-cooling model provides a plausible mechanism to bridge geography and timing — a climatic shock forces dramatic changes in trade and food supply that then facilitate pathogen movement along existing human networks.

That chain of cause-and-effect highlights a crucial point often underappreciated in pandemic studies: environmental events and economic decisions interact to change disease risk. A short-term climate perturbation can cascade into agricultural collapse, commodity reallocation, and altered human mobility — all of which modify opportunities for pathogens to leap into new populations.

Scientific context and publication

The research draws on well-established climate proxies: ice cores for atmospheric chemistry and tree rings for temperature reconstruction. By aligning those physical proxies with documentary evidence about weather, harvests and trade, the authors built a temporally coherent narrative. Their findings were published in Communications Earth & Environment in 2025, contributing to an expanding literature that links volcanism, short-term climate anomalies and socioeconomic stress in the medieval world.

Beyond medieval history, this study illustrates methodological strengths of interdisciplinary research. Combining paleoclimatology, history, archaeology and epidemiology strengthens confidence in causal claims, especially when multiple independent lines of evidence converge on the same years and regions.

Expert Insight

"This paper is a strong example of how environmental shocks can reshape human networks in ways that enable disease spread," says Dr. Elena Marinos, a fictional paleoclimatologist and science communicator. "When grain traders changed their routes to avert famine, they unknowingly created a corridor for Yersinia pestis. It’s a reminder that pandemics often emerge at the intersection of nature and human decisions."

Her comment underscores the practical lesson: understanding past pandemics requires more than pathogen genomics. It also calls for attention to the social and environmental triggers that set the stage — an insight relevant today as climate variability continues to affect food security and mobility.

Implications and future directions

The study does not claim to have identified the exact volcano; the likely source remains unidentified, possibly tropical, and could represent one large eruption or a cluster. Future work could refine the geographic source by comparing sulfate isotope signatures from ice cores, assessing volcanic sulfate deposition patterns, and searching for tephra (volcanic ash) layers that could tie the event to a specific eruption.

On the epidemiological side, more ancient DNA sampling from archaeological human remains along Black Sea trade routes and ports could further test the reintroduction scenario and clarify timing. Likewise, modeling how fleas and rodents survive aboard different cargo types would help quantify transmission risk during maritime journeys.

In short, the new hypothesis stitches together climate science, historical records and disease ecology to explain how a distant volcanic eruption may have indirectly triggered one of history’s worst pandemics. It’s a story of interconnected systems — atmosphere, crops, commerce and microbes — where a single environmental nudge sent shockwaves through medieval society.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

DaNix

is this even true? sounds plausible but how sure are they about the 1345 eruption source, no tephra found right, seems like a big assumption to me.

labcore

Wow never thought a volcano could nudge history like that. Crazy chain, climate trade and microbes all linked. Feels uncanny, kinda chilling

Leave a Comment