6 Minutes

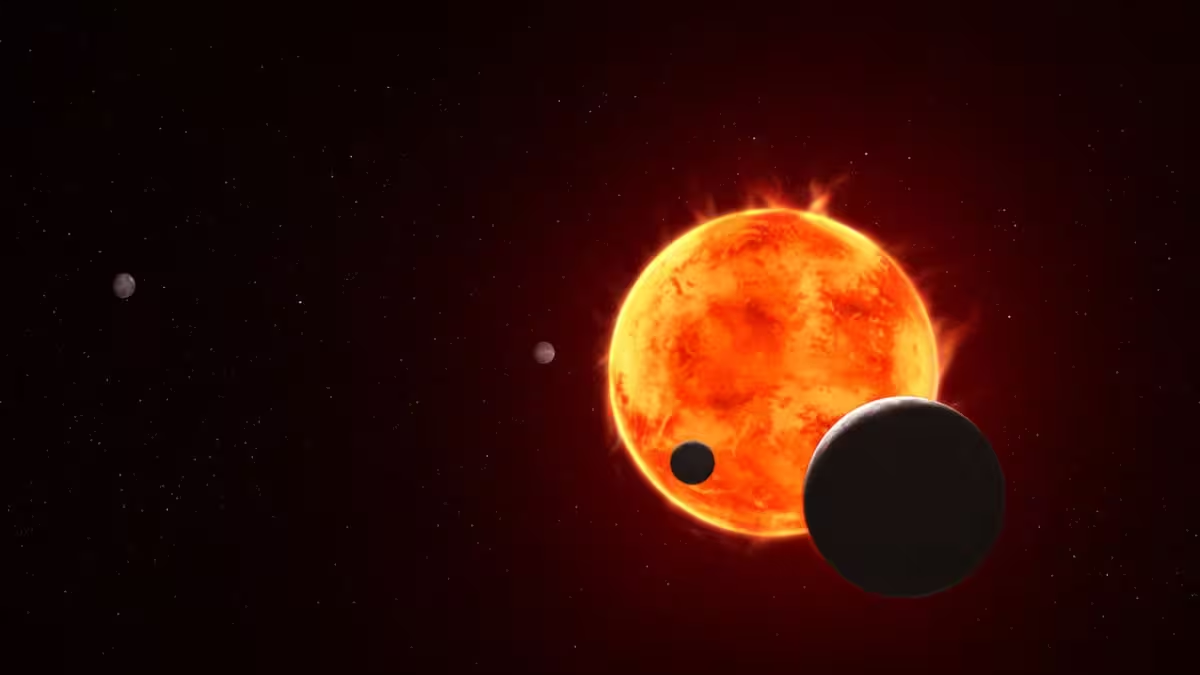

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has returned its first detailed look at TRAPPIST-1e, one of seven Earth-sized worlds orbiting a nearby red dwarf. Early spectra hint at methane, a potential biosignature or geosignature — but scientists warn the signal is ambiguous and could instead come from the star itself. Here’s what the new results mean, how researchers are testing the possibilities, and which missions and techniques could settle the question.

Why TRAPPIST-1e matters: a small world with big potential

Located about 39 light-years from Earth, the TRAPPIST-1 system resembles a compact, scaled-down solar system: seven roughly Earth-sized planets packed into orbits well inside Mercury’s path. Among them, TRAPPIST-1e stands out because it orbits within the star’s habitable — or “Goldilocks” — zone, where temperatures could allow liquid water on the surface if the planet retains an atmosphere.

That combination — Earth-sized, temperate orbit, and proximity to our solar system — makes TRAPPIST-1e a top target for atmospheric characterization. Detecting gases like methane, water vapor, carbon dioxide, or oxygen would be a major step toward understanding the planet’s geology, climate, and potential for life.

How Webb searched for an atmosphere

Scientists used Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) to observe four transits of TRAPPIST-1e. During a transit, a planet crosses in front of its star and a fraction of starlight filters through any atmosphere, imprinting absorption features characteristic of specific molecules. By stacking spectra from multiple transits, researchers can improve sensitivity to faint atmospheric signals.

Transit spectroscopy: the basics

- Starlight passing through a planetary atmosphere loses specific wavelengths where gases absorb light, producing spectral fingerprints.

- Repeated transits help distinguish real planetary features from random noise and instrumental effects.

- However, when the host star is an ultracool M dwarf, stellar effects can mimic or mask planetary signals.

The Webb team’s initial analysis, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters and led in part by researchers including Sukrit Ranjan of the University of Arizona, reported hints of methane in the combined NIRSpec data. But Ranjan and colleagues immediately emphasized caution: TRAPPIST-1 is an ultracool red dwarf whose own atmospheric and surface processes can produce spectral features that contaminate transit observations.

Methane: a hopeful hint or stellar impostor?

Methane (CH4) is interesting because it can be produced biologically or geologically. On Earth, methane has both biological and abiotic origins. In the colder, molecule-rich environments around M dwarfs, however, methane-like absorption could arise in the star’s outer layers or from instrumental artifacts tied to the star’s spectrum.

Ranjan’s follow-up work modeled several scenarios in which TRAPPIST-1e could host a methane-rich atmosphere. The most familiar analog is Titan, Saturn’s moon, where a thick nitrogen atmosphere with abundant methane creates strong spectral signatures. But the simulations showed that a Titan-like composition for TRAPPIST-1e is unlikely given the current data. In many modeled cases, the methane-like features are more plausibly explained as stellar contamination or observational noise.

“If it has an atmosphere, it’s habitable,” Ranjan said in describing the stakes. “But right now, the first-order question must be, ‘Does an atmosphere even exist?’” The answer remains unresolved: Webb’s hints are tantalizing but not yet definitive.

Separating planet from star: observational strategies

Because M dwarfs are small and cool, their spectra contain molecular lines and variability that complicate transit spectroscopy. To untangle planetary signals from stellar effects, astronomers are pursuing several approaches:

- Dual-transit observations: observing the system when two planets transit simultaneously, including an airless inner planet as a control, helps isolate the star’s imprint from any planetary atmosphere.

- Longer monitoring and more transits: accumulating many transits increases signal-to-noise and reveals whether features persist across time.

- Multi-instrument, multi-wavelength campaigns: combining Webb observations with other telescopes reduces the risk that instrument-specific systematics drive the result.

Future tools: Pandora and improved techniques

Webb wasn’t built specifically to study small, Earth-like exoplanets; it was designed decades before the prevalence of such worlds was known. Still, Webb’s sensitivity makes it the best tool available today for initial atmospheric studies. To complement Webb, NASA is developing smaller missions targeted at exoplanet host star characterization.

One such mission is Pandora, led by Daniel Apai at the University of Arizona, scheduled for launch in the mid-2020s. Pandora is a dedicated small satellite designed to monitor host stars and their transits continuously, providing high-cadence measurements of stellar variability before, during, and after planetary transits. By characterizing stellar contamination directly, Pandora aims to improve the confidence of atmospheric detections for planets like TRAPPIST-1e.

Meanwhile, the Webb observing team plans an expanded campaign, including dual-transit observations that pair TRAPPIST-1e with its inner, likely airless neighbor TRAPPIST-1b. The combined data set and refined analysis techniques should help determine whether the methane-like feature is planetary or stellar in origin.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Hernandez, an exoplanet spectroscopist at a major research university (not involved with the Webb TRAPPIST-1 papers), commented: “This is exactly the kind of scientific caution we expect at the frontier. Webb gives us unprecedented sensitivity, but M-dwarf stars are tricky. Hints of methane are exciting because methane can point to active geology or even biology, but the default position right now should be skepticism. The next steps — more transits, simultaneous observation of multiple planets, and focused stellar monitoring from missions like Pandora — will be decisive.”

Until those decisive observations arrive, TRAPPIST-1e remains a promising but unresolved case. Webb’s early data mark an important milestone: for the first time, we can probe an Earth-sized world’s atmospheric fingerprints around a nearby red dwarf. The ambiguity in the methane signal is not a setback; it is the natural state of discovery, pointing the way to smarter observations and better instruments.

Researchers and observers worldwide will be watching TRAPPIST-1 closely over the coming years, and each new transit will sharpen the picture. Whether TRAPPIST-1e ultimately proves to have a methane-rich atmosphere, a thin airless surface, or something entirely different, the effort will significantly advance our methods for searching for habitable environments beyond the solar system.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

skyspin

Methane? is it from the planet or the star, really. Feels premature, they need more transits, dual-transit trick sounds smart, but I'm skeptical if instrument systematics can mimic CH4... if that's real then

astrobit

Wow didnt expect Webb to get this close... methane hint?? If true, wild. But those M dwarf quirks scare me, stellar contamination looks real. Pandora can't come soon enough

Leave a Comment