5 Minutes

New research from Yale offers a clear biochemical explanation for a long-observed fact: regular exercise reduces cancer risk. In mice carrying breast cancer or melanoma, physical activity changed how the body allocated glucose and energy, effectively boosting muscle metabolism while constraining the fuel available to tumors. The result was slower tumor growth, especially in animals on high-fat diets that ran voluntarily.

How the experiment was set up and what scientists measured

The team led by physician-scientist Brooks Leitner tracked metabolic activity in mice with implanted breast cancer or melanoma tumors. Animals were divided by diet and by activity level: some had access to a running wheel, others remained sedentary. The researchers used molecular tracers that reveal where glucose is metabolized in living tissue, allowing them to map how energy flowed between organs, muscles and tumors.

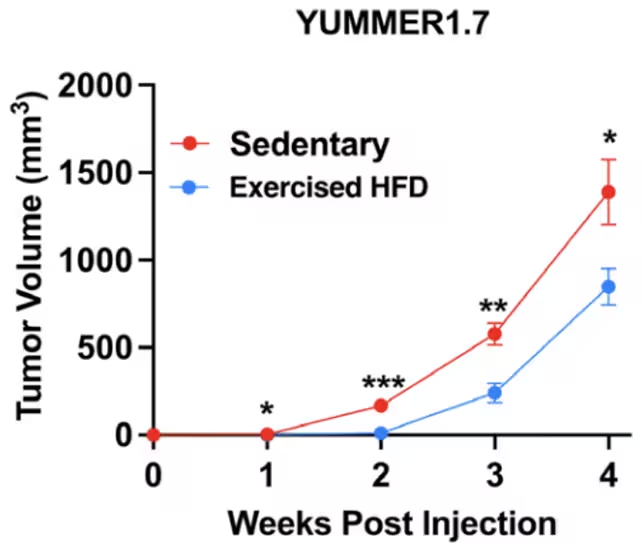

After four weeks, active mice on a high-fat diet showed a striking reduction in tumor size compared with sedentary peers. As the authors note, 'Obese mice which underwent four weeks of voluntary wheel running after tumor injection exhibited nearly a 60 percent reduction in tumor size.' Tumors were consistently smaller in mice that exercised. The data shown here is for mice carrying melanoma tumours. (Leitner et al., PNAS, 2025)

What the metabolic data reveal

The molecular tracers made clear that exercise reroutes glucose toward skeletal muscle and away from tumors. Muscle cells become more metabolically active with sustained exercise, burning more glucose and other fuels. Tumors, which rely heavily on glucose for rapid growth, appear to be deprived of that ready energy source and switch into a high-stress survival state.

Tumors were consistently smaller in mice that exercised. The data shown here is for mice carrying melanoma tumours. (Leitner et al., PNAS, 2025)

On a genetic level, the team found 417 metabolism-related genes that were expressed differently in active mice versus sedentary, lean mice. One notable change was a decrease in activity of the mTOR protein pathway within tumors. mTOR is a central regulator of cell growth and metabolism; dialing it down can limit tumor proliferation and survival. Taken together, the data identify glucose as a key metabolic mediator of the tumor-suppressive effects of exercise and suggest a molecular route by which physical activity can slow cancer progression.

Why this matters for prevention and potential therapies

These findings do not imply that exercise alone can prevent or cure cancer. Cancer is a multifaceted disease with genetic, environmental and immunological drivers. But the study adds a powerful mechanistic layer to epidemiological evidence that active lifestyles reduce cancer incidence and mortality. The effect was visible across two tumor types in mice, suggesting the metabolic benefit of exercise may not be limited to one specific cancer.

Importantly, the researchers emphasize dose and timing considerations. The metabolic relationship between muscles and tumors, and the capacity of exercise to slow tumor growth, may depend on how long and how frequently animals exercise. Mice that exercised for two weeks before tumor implantation also developed smaller tumors than sedentary mice, hinting that preexisting fitness or early activity may be protective.

From a translational standpoint, these metabolic shifts point to potential therapeutic angles. If exercise suppresses tumors by diverting glucose and downregulating pathways such as mTOR, then interventions that mimic those effects might benefit patients who cannot exercise because of illness or disability. The authors suggest that deeper study of exercise-modified molecular pathways could reveal new targets for precision oncology.

Next steps: testing the findings in people

The big question is whether the same glucose rerouting and gene-expression changes occur in humans. The Yale group plans to extend their work to human tumors and to conduct controlled studies that vary exercise type, intensity and duration. That will clarify how fitness levels influence molecular pathways altered by exercise and whether those pathways can be harnessed therapeutically.

Expert Insight

’This paper gives us a tangible metabolic picture of how activity fights cancer,’ says a clinical oncologist familiar with the study. ’We already recommend exercise for overall health; now we have mechanistic reasons to examine it as an adjunct to therapy, especially when metabolic pathways like mTOR are involved.’

Taken together, the mouse data strengthen a growing argument: regular physical activity reshapes whole-body metabolism in ways that can limit tumor growth. The immediate clinical takeaway remains cautious — exercise is beneficial but not a stand-alone treatment — yet the metabolic clues uncovered here open new doors for prevention strategies and drugs that replicate exercise’s tumor-starving effects.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

mechbyte

Hmm is this even true in ppl tho? Running wheels + high fat mice seems odd. Want to see human studies and whether immune changes play a role, not just glucose. quick thought.

bioNix

Wow, didn't expect exercise to literally reroute glucose away from tumors. If this pans out in humans, big implications. Mice != people tho, curious about intensity, timing and diet effects…

Leave a Comment