7 Minutes

New research shows that pregnant people who drink well water downstream of PFAS contamination face markedly higher risks of adverse birth outcomes, including low birth weight, preterm delivery and infant death. By using the natural flow of groundwater to compare upstream and downstream wells, investigators provide unusually strong real-world evidence that so-called "forever chemicals" harm fetal and neonatal health.

Using wells as a natural experiment: how scientists isolated PFAS effects

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are synthetic chemicals prized for their resistance to heat, water and oil. That durability makes them useful in a wide range of products, but it also means PFAS persist in soil and groundwater long after they are released. Instead of exposing people deliberately, researchers turned to geography: the slow downstream migration of PFAS through groundwater creates a sharp difference in exposure between homes served by wells downstream of contaminated sites and those served by wells upstream.

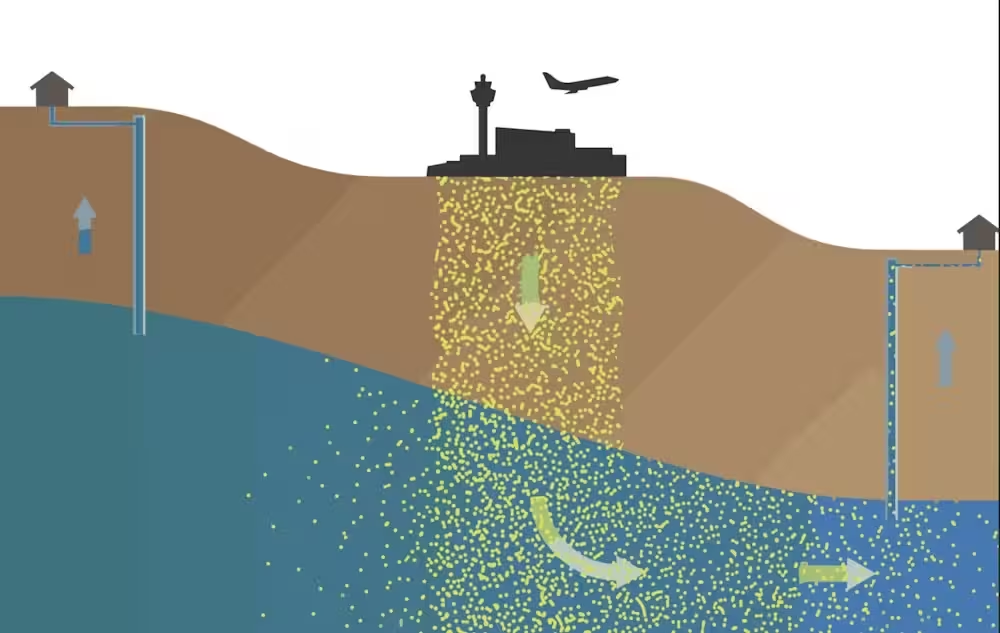

A conceptual illustration shows how PFAS can enter the soil and eventually reach groundwater, which flows downhill. Industries and airports are common sources of PFAS. The homes show upstream (left) and downstream (right) wells. (Melina Lew)

The team analyzed every recorded birth in New Hampshire from 2010 to 2019, then focused on 11,539 births that occurred within about 3.1 miles (5 kilometers) of a known PFAS-contaminated site where the mother received water from a public well. Because the precise locations of utility wells aren’t public, residents typically would not have known whether their drinking water was contaminated. The researchers confirmed exposure differences using PFAS testing data that showed higher concentrations in downstream wells than upstream ones.

What the study found: substantial increases in the most serious outcomes

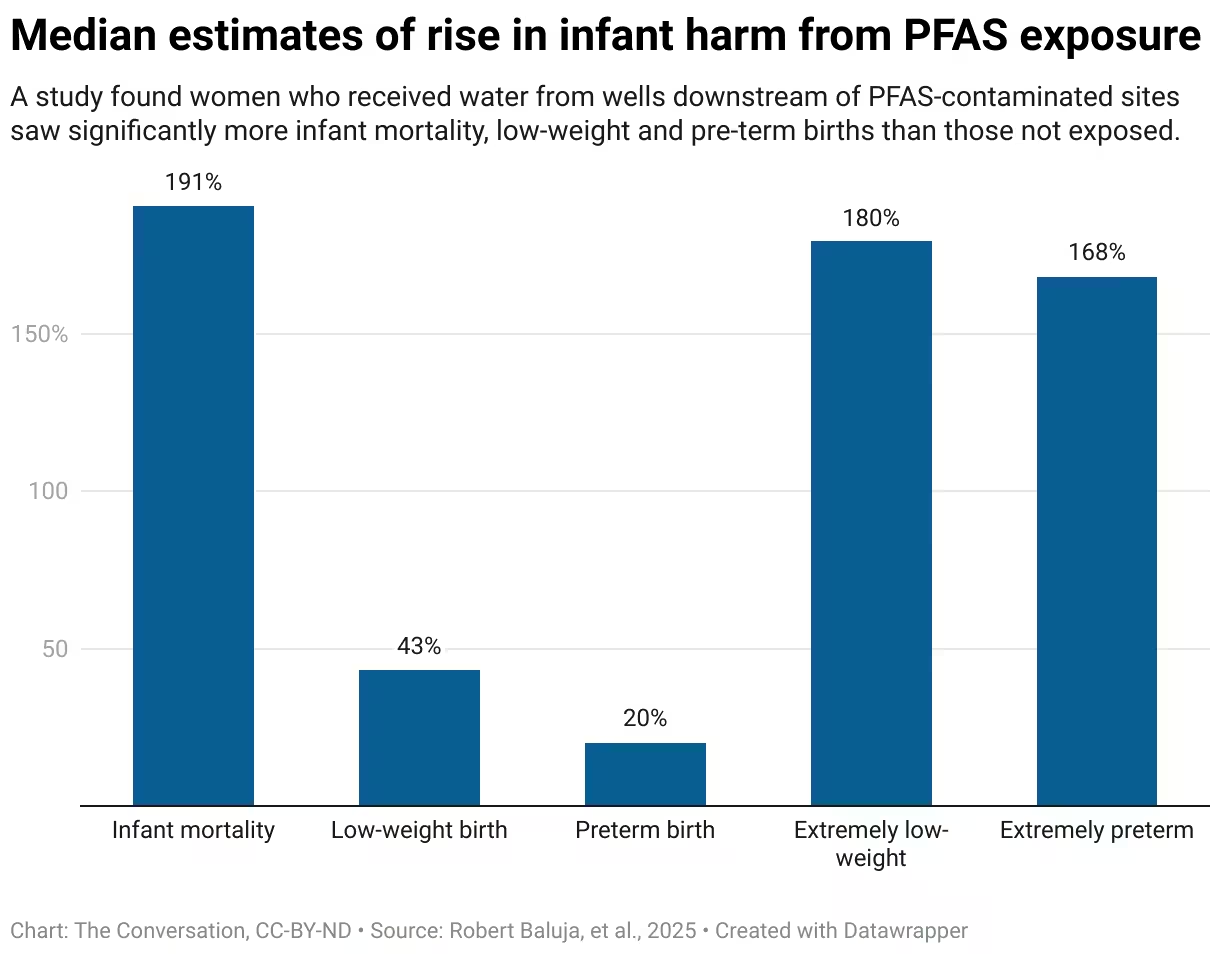

The results are stark. Compared with mothers served by upstream wells, those using downstream wells showed higher risks across multiple indicators:

- A 43% greater chance of delivering a low-weight baby (under 2,500 grams / 5.5 pounds).

- A 20% higher risk of preterm birth (before 37 weeks).

- A 191% increase in infant mortality (death within the first year).

When researchers examined the most severe cases—infants born extremely small or extremely early—the differences grew even larger. Downstream water users had a 180% greater chance of an infant weighing under 1,000 grams (about 2.2 pounds) at birth and a 168% higher chance of delivery before 28 weeks.

Put another way, the investigators estimate that, per 100,000 births, PFAS exposure downstream of contaminated sites corresponds to roughly 2,639 additional low-weight births, 1,475 additional preterm births and 611 more deaths during the first year of life. For the very smallest and earliest births, the figures are about 607 and 466 additional cases per 100,000 births, respectively.

Scientific context: why this study matters

Most evidence linking PFAS to reproductive harm has come from animal experiments or from studies that measure PFAS in blood and look for statistical associations with health outcomes. Those approaches are valuable but have limitations: lab animals differ biologically from humans, and blood-level correlations can be confounded by other health or behavioral factors. By exploiting hydrology to create a quasi-experimental comparison, this study brings epidemiology closer to a randomized design without ethical problems.

The research focused on long-chain PFAS compounds—specifically PFOA and PFOS—which were widely used in the U.S. for decades. Although U.S. manufacturers stopped producing these particular compounds domestically years ago, their persistence means soil and groundwater remain reservoirs of exposure. Short-chain PFAS replacements are increasingly common and may behave differently in the environment and the body; their health effects remain less well characterized.

Putting a price on health: economic costs of PFAS-linked births

To help policymakers weigh cleanup costs, the authors translated health impacts into monetary terms. Using established methods that account for increased medical spending, diminished lifetime health, and reduced earnings, they estimated that the lifetime societal cost of low-weight births attributable to PFAS is about $7.8 billion for each year’s cohort of affected babies. Additional costs tied to preterm births and infant mortality add roughly $5.6 billion, with some overlap between categories.

Those figures are set against estimates of the cost to utilities to treat drinking water: one analysis for the American Water Works Association suggested utilities would spend about $3.8 billion annually to remove PFAS to meet current EPA limits. While that number addresses infrastructure costs paid by utilities and customers, the new health-cost estimates highlight the broader, long-term public burden from fetal and infant harms.

Treatment options and public-health implications

Removing PFAS from drinking water is an active area of research and deployment. Long-chain PFAS such as PFOA and PFOS can be effectively reduced with granular activated carbon filtration, either at the municipal treatment level or with point-of-use home systems. However, filters must be properly sized and replaced on schedule, and not all consumer filters remove all PFAS species.

PFAS exposure pathways are broader than drinking water: these chemicals also appear in some foods, consumer products and indoor dust. Still, the study’s findings underscore a particular urgency for pregnant people: exposure through drinking water, even at low concentrations, appears to raise the likelihood of the most severe birth outcomes.

Expert Insight

"This study uses a clever, geography-based approach to isolate the effects of PFAS in real-world populations," says Dr. Emily Carter, an environmental epidemiologist at the New England Public Health Institute. "The increases in extremely preterm and very low-birth-weight infants are especially worrisome because those outcomes carry lifelong health and developmental consequences. Policymakers should see these results as strong evidence that investing in source controls and water treatment yields substantial public-health benefits."

What remains unknown and next steps

Important questions remain. The study focused on long-chain compounds; the human health implications of many newer short-chain PFAS are still being worked out. Researchers also need to understand dose–response relationships, windows of greatest vulnerability during pregnancy, and the combined effects of multiple exposure routes (water, food, dust).

From a regulatory standpoint, quantifying benefits in dollars and lives helps inform cost–benefit decisions about cleanup standards and treatment investments. For clinicians and expectant parents, the message is pragmatic: where PFAS contamination is possible, point-of-use filtration that targets PFAS can reduce exposure, and public-health agencies should prioritize testing in at-risk communities.

Ultimately, the study adds to a growing scientific consensus: PFAS contamination of groundwater is not just an environmental problem but a reproductive-health emergency for communities downstream of industrial, firefighting and landfill sources. Effective monitoring, targeted remediation and clearer guidance for pregnant people are urgent next steps.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

atomwave

Wait, is the upstream/downstream method solid? Could local demographics or other pollutants explain it? curious, not mad

bioNix

This is heartbreaking. How many moms had no clue their well was poisoned? Seems like policy failed us, urgent fix pls..

Leave a Comment