5 Minutes

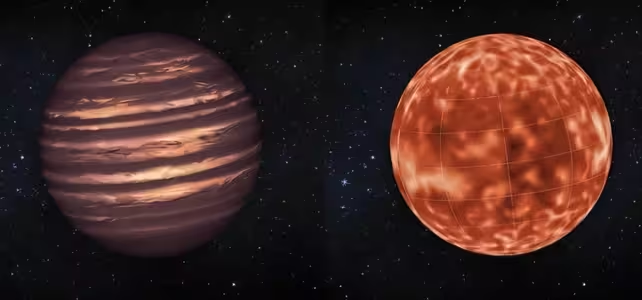

We picture giant exoplanets as oversized Jupiters — banded, stormy and familiar. New observations and atmospheric models suggest many of these so-called "super-Jupiters" may look very different: hotter, redder, and more chaotic in cloud structure than anything in our Solar System.

Jupiter, brown dwarfs and the mass gap

To understand what makes a super-Jupiter unusual, it helps to set the scene. Planets, brown dwarfs and stars are separated primarily by mass and the nuclear reactions they can sustain. A planet is massive enough to become round under its own gravity but not to ignite sustained hydrogen fusion. Stars do exactly that. Between them lie brown dwarfs: too small to fuse hydrogen, but sometimes large enough to burn a little deuterium.

In rough terms, objects up to about 10 times Jupiter's mass are typically classified as planets, while those above roughly 90 Jupiter masses are stars. Brown dwarfs sit in that middle ground. That classification matters because mass controls internal heat and atmospheric behavior — and those factors influence what the object looks like when we image it.

VHS 1256b: a super-Jupiter that glows red

One of the best-studied objects in this regime is VHS 1256b. With a mass near 20 Jupiters it occupies a borderline zone where many would have expected a Jupiter-like appearance. But direct imaging with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) paints a different picture: VHS 1256b emits appreciable deep-red light and has a surface temperature around 1,300 K — far hotter than Jupiter's roughly 170 K.

Spectra from JWST reveal signatures of heavy cloudiness and dust in VHS 1256b's atmosphere. Those dusty, large-scale storm systems cause the planet's brightness to vary, producing fluctuations reminiscent of the variability seen in small, cool stars. Instead of crisp equatorial bands, the atmosphere looks patchy and turbulent.

Why heat reshapes atmospheric patterns

On Jupiter, well-ordered bands and long-lived storms arise from a balance of strong zonal (east–west) winds and heat exchanges between atmospheric layers. Super-Jupiters, however, are far warmer. That extra heat injects more energy into the atmosphere, amplifying vertical motions and turbulent mixing. Modelers in the new study show that this turbulence tends to break up the familiar banded pattern, producing chaotic cloud decks and localized storms.

So while artistic renderings historically treated massive exoplanets as "big Jupiters," physics points to greater diversity. Composition, internal heat flux, rotation rate and stellar irradiation all combine to determine whether a massive gas world shows bands or a mottled, storm-dominated face.

What this means for direct imaging and characterization

The typical artistic view of a Jupiter-like world (left) compared to a look based on new research (right). (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

For researchers using telescopes like JWST and ground-based observatories, these findings reshape expectations. Photometric variability — the lightcurve flicker caused by rotating storms — can reveal atmospheric patchiness even when spatially resolving a planet is impossible. Spectroscopy that detects dust and molecular absorbers (water, methane, carbon monoxide) helps infer temperature structures and cloud composition.

Practically, this means surveys searching for and classifying directly imaged exoplanets need models that include turbulent, dust-rich atmospheres. Interpreting colors, spectra and brightness changes without that complexity risks misclassifying objects or misestimating their temperatures and masses.

Expert Insight

"Higher internal heat changes everything," says Dr. Elena Marques, an astrophysicist who studies exoplanet atmospheres. "When you push temperatures into the hundreds or thousands of kelvin, condensates form lofted clouds and dust. Those materials absorb and scatter light differently, and the atmospheric circulation shifts from ordered jets to chaotic storms. The result is a planet that looks alien compared to Jupiter."

Future observations will target a broader sample of super-Jupiters and warm brown dwarfs to test whether VHS 1256b is typical or an outlier. As instruments improve and models incorporate turbulent cloud physics, astronomers will refine how mass and heat map to visual appearance across the largest exoplanets.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

astroset

Is this just one oddball? VHS 1256b might be extreme, but are models robust enough, or are we overfitting noisy spectra? curious...

atomwave

wow, didn't expect giant Jupiters to be fiery red and so chaotic. kinda mind blown, clouds like dust storms? sounds wild, hope more JWST pics soon

Leave a Comment