5 Minutes

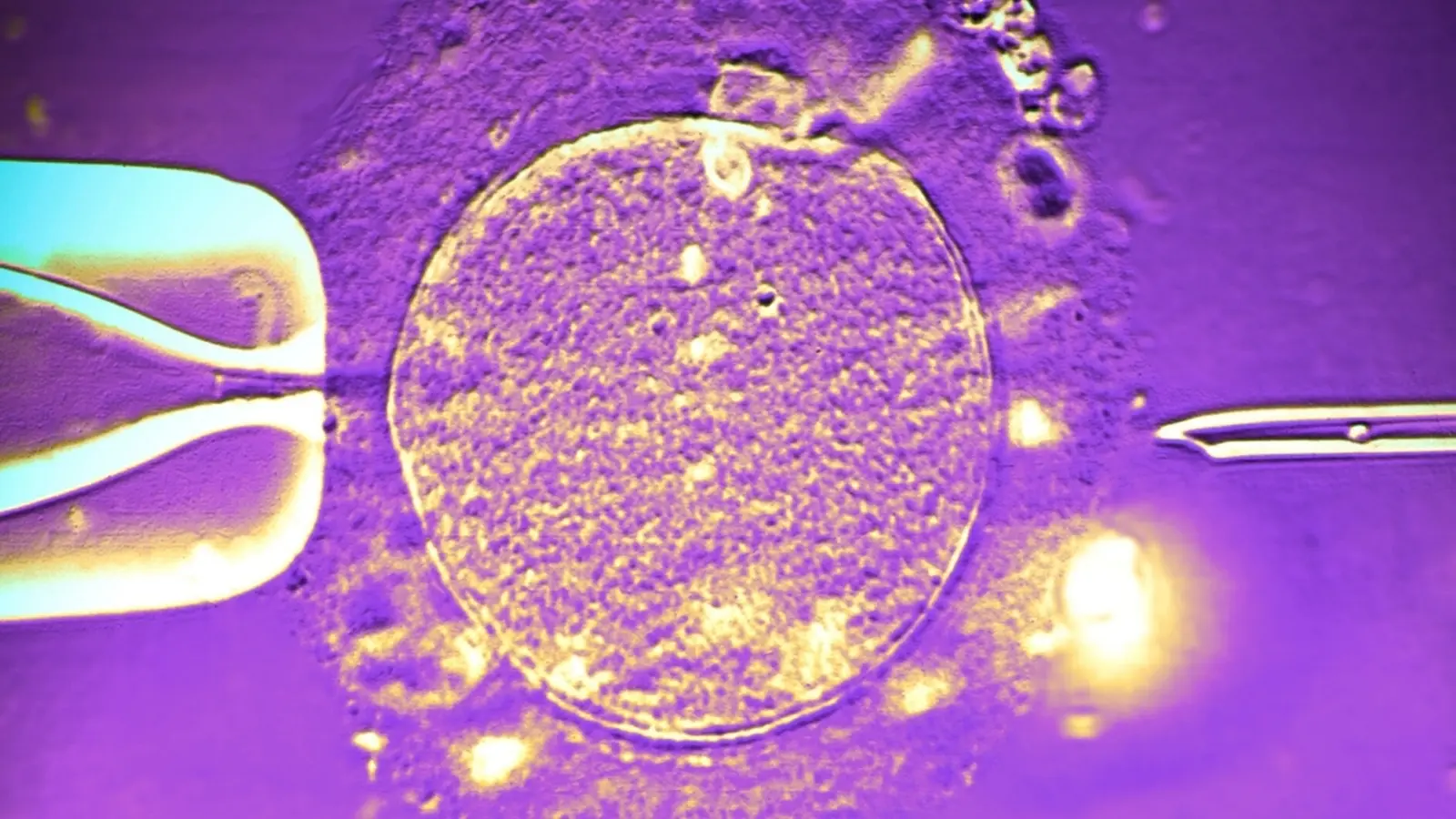

A sperm donor who carried a rare cancer-risk gene has been linked to nearly 200 children born across multiple countries, Denmark's public broadcaster reported. The case highlights limits in routine genetic screening, cross-border fertility practices, and the challenges posed by mosaic mutations that appear in only some sperm cells.

How the case came to light

Denmark's European Sperm Bank (ESB), one of the world's largest sperm suppliers, learned in April 2020 that a child conceived with donated sperm had been diagnosed with cancer and carried a genetic mutation. Initial testing of the donor's stored samples did not reveal the mutation, and the bank temporarily suspended sales while further analysis took place. Sales resumed after the first round of screening.

Three years later, the ESB was notified of at least one more child conceived with sperm from the same donor who had developed cancer. Subsequent tests on several samples indicated the donor carried a previously undescribed mutation in TP53, a gene known for its role as a tumor suppressor. The bank blocked further use of his sperm in late October 2023.

What scientists mean by a 'rare' TP53 mutation

The ESB and Danish health authorities described the mutation as rare and unusual. According to the ESB, the specific TP53 alteration was detected only in a small fraction of the donor's sperm cells and was not present in the rest of his body. In other words, the donor appeared asymptomatic because the mutation was largely confined to his germline—an example of gonadal mosaicism.

TP53 is a critical cancer-related gene that helps repair DNA or trigger cell death when damage is severe. Germline mutations in TP53 are classically associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a hereditary condition that dramatically increases cancer risk. But mosaic mutations—present in only some cells—can be much harder to spot during standard donor screening.

Numbers, screening limits and legal gaps

The Danish Patient Safety Authority reported that 99 children were born in Denmark following treatment with the donor's sperm; the ESB told authorities the donor's gametes had been used by 67 clinics in 14 countries. Public broadcaster DR put the total number of children fathered at at least 197 before the abnormality was discovered.

Fertility clinics typically run genetic screens to reduce the risk of passing on severe inherited disorders. However, most routine tests target common or known pathogenic variants and assume mutations, if present, are detectable in the sampled tissue. Mosaic mutations restricted to a subset of sperm cells can evade detection, especially when mutation frequency is low.

There are national rules in some European countries limiting the number of children per donor, but no universal international cap. The ESB has said it has been involved in more than 70,000 births worldwide over two decades and set an internal maximum of 75 families per donor at the end of 2022. Cross-border donation and differing national regulations complicate oversight and tracking when a donor's material is distributed globally.

Regulatory and ethical implications for families

For families and clinics, the case raises practical questions: how to notify recipients, how to search for affected children across borders, and when to offer genetic testing or counseling. Health authorities face the delicate balance between protecting recipient privacy and ensuring potentially affected children and adults receive timely information and medical follow-up.

Expert Insight

Dr. Emily Carter, a clinical geneticist at a major university hospital, commented that the case underlines the limits of standard screening: 'When a mutation exists only in a portion of a donor's sperm, routine tests—often based on a single sample—can miss it. This is mosaicism at work. For fertility services, the response should include more robust donor follow-up, clearer reporting channels between clinics internationally, and accessible genetic counseling for families.'

As assisted reproduction continues to cross borders and scale, experts say the field may need better international standards for donor tracking, transparent reporting of genetic findings, and updated screening protocols that consider mosaic mutations where feasible.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

fxHunt

Is this even true? If tests miss mosaic sperm mutations then the whole system's broken... who traces kids abroad?

bioNix

Whoa, scary stuff. Mosaic mutations are stealthy, how do you screen what you can’t see? Families need answers, ugh.

Leave a Comment