5 Minutes

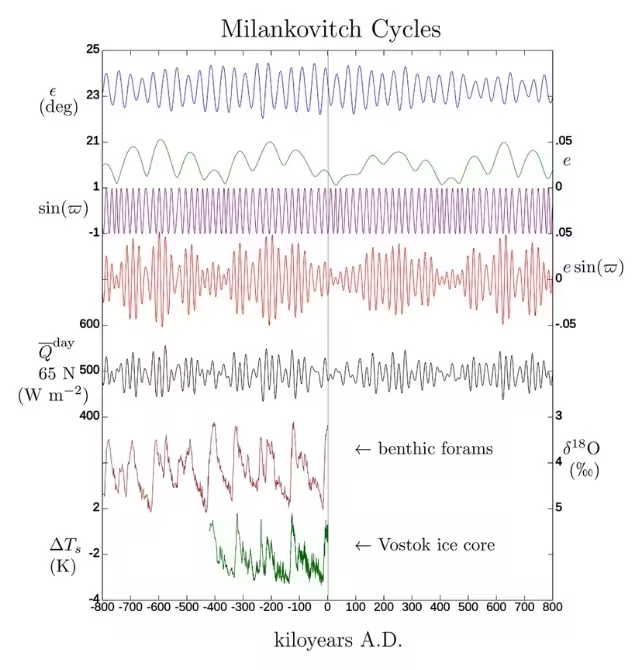

Earth's long-term climate swings — the alternation between ice ages and warmer intervals — are often explained by Milankovitch cycles: slow changes in Earth's orbit and tilt that modulate how sunlight falls on the planet. New modeling shows these cycles are not just an Earth–Sun duet. Mars, surprisingly, plays a measurable role in pacing our ice ages and shaping orbital rhythms over millions of years.

A surprising gravitational player in Earth's climate

For decades, scientists studying Milankovitch cycles emphasized the gravitational influence of the largest neighbors: Jupiter and Venus. Their interactions produce the steady 405,000-year eccentricity "metronome" that appears in geological records worldwide. But a recent set of computer experiments led by planetary scientist Stephen Kane revisited those assumptions and tested a bold question: what if Mars had a different mass?

The red planet Mars, as captured here by the Hope orbiter, has an unexpected impact on our seasons.

By running multi-million-year simulations in which Mars's mass was systematically varied from zero to ten times its actual value, the team mapped how Earth’s orbital elements — eccentricity, obliquity (axial tilt), and precession — responded. The result: Mars matters. Not just a minor background actor, Mars helps set the timing and strength of several key climate cycles.

How Mars changes Earth's orbital rhythms

Some features remained robust across all scenarios. The 405,000-year eccentricity cycle, a product of Venus–Jupiter interactions, persisted even when Mars's mass changed dramatically. That cycle acts like a long-term metronome for Earth's climate changes, anchoring variations in insolation (incoming solar radiation).

However, shorter and climatically critical rhythms — notably the roughly 100,000-year cycles associated with ice age pacing — showed a clear dependence on Mars. As the simulated mass of Mars increased, these ~100,000-year oscillations lengthened and gained power, reflecting stronger coupling among the inner planets' orbits. Perhaps most strikingly, when Mars's mass was set near zero, a number of important cycles vanished, including a 2.4-million-year "grand cycle" tied to slow resonant interactions between Earth’s and Mars’s orbital precession.

Earth's seasons seem to be in part controlled by the presence of Mars. Image captured by Apollo 17.

The team's models also showed Mars influencing Earth's obliquity. The familiar ~41,000-year obliquity cycle recorded in sediment and ice cores lengthened as Mars grew more massive in the simulations, shifting toward dominant periods of 45,000–55,000 years when Mars was assumed ten times heavier. Such changes would alter the timing and magnitude of ice sheet growth and retreat — with clear consequences for sea level, ecosystems, and Earth's carbon cycle.

Past and future Milankovitch cycles via VSOP model Graphic shows variations in five orbital elements: Axial tilt or obliquity (ε). Eccentricity (e). Longitude of perihelion (sin(ϖ)). Precession index (e sin(ϖ)) Precession index and obliquity control insolation at each latitude: Daily-average insolation at top of atmosphere on summer solstice () at 65° N Ocean sediment and Antarctic ice strata record ancient sea levels and temperatures. (Incredio)

Why this discovery matters beyond Earth

Recognizing Mars as a non-negligible driver of Milankovitch cycles reframes how we think about planetary habitability. For exoplanets, the architecture of the planetary system — especially the masses and orbital relationships of neighboring worlds — could strongly influence long-term climate stability. A terrestrial planet paired with a massive neighbor in the right resonance might avoid extreme, long-term glaciation or could instead experience amplified climate swings. That has direct implications for interpreting exoplanet observations and prioritizing targets in the search for life.

These findings, uploaded to the preprint server arXiv, underscore that Earth's climate history is a product of its broader planetary neighborhood. The Sun–Earth coupling remains central, but the gravitational choreography of the inner Solar System, with Mars unexpectedly in the spotlight, sets the tempo for climate on geological timescales.

Expert Insight

"This work is a reminder that planetary systems are dynamic, interconnected machines," says Dr. Elena Morales, a planetary scientist not involved in the study. "Even a modest world like Mars can change the resonance structure of the inner system and, over millions of years, nudge a planet’s climate in meaningful ways. For exoplanet research, that means we need to model whole systems, not just single worlds."

Future work will refine these simulations, incorporate additional dynamical effects, and use paleoclimate proxies to test model predictions against Earth's geological record. Meanwhile, the study opens a fresh line of inquiry into how neighbors shape the long-term climate of rocky planets — both here and among the stars.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

DaNix

Is this even true? If Mars had near zero mass would those 2.4 Myr cycles vanish in rocks too... I'm skeptical, need palaeo evidence, not just sims

astroset

wow didnt expect Mars to mess with Earth's ice ages like that... kinda mindblowing. planets tugging on each other over millions yrs, wild!

Leave a Comment