3 Minutes

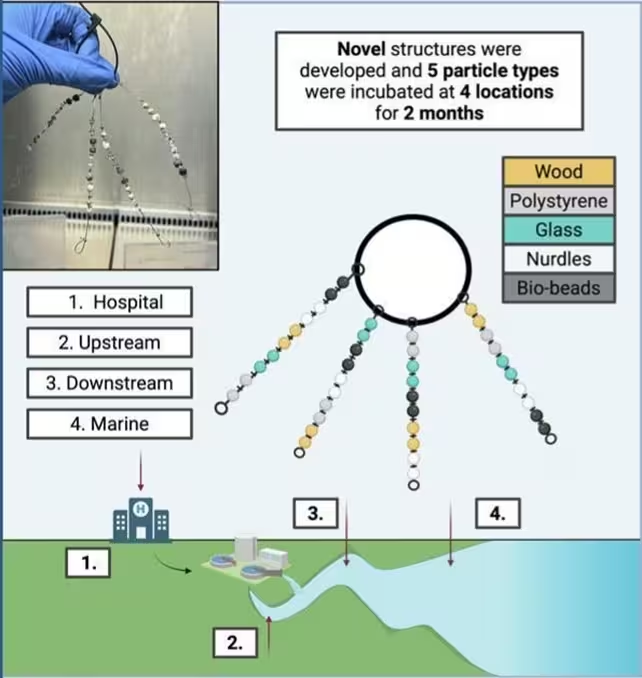

Microplastics are more than an environmental nuisance: tiny fragments of plastic in sand and seawater can host diverse bacterial communities, creating hotspots for microbes that may threaten wildlife and people. New research published in Environment International highlights these risks and offers practical advice for volunteers and coastal managers.

When plastic becomes a microbial habitat

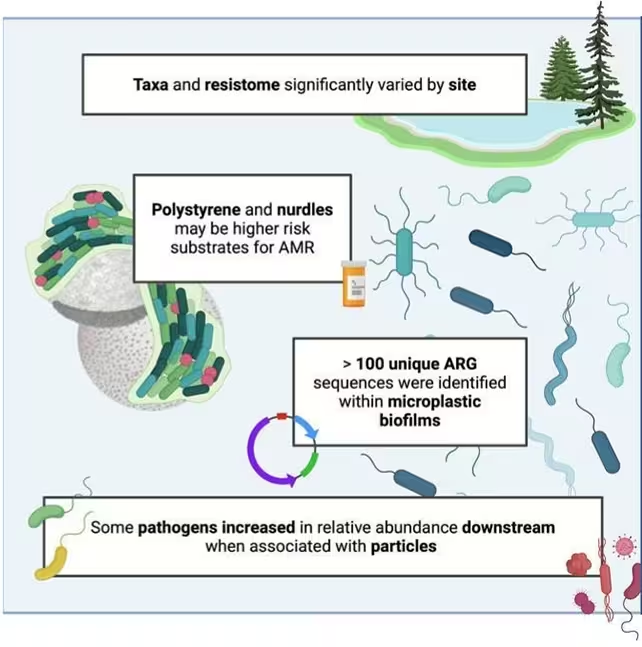

Scientists have long studied the chemical toxicity of microplastics. Recent work adds another layer of concern: plastics in the environment — from microscopic beads to weathered fragments — attract bacteria and form biofilms. These biofilms provide protective niches where microbes can multiply and sometimes exchange genetic material, including antimicrobial-resistance genes.

Why that matters for humans and wildlife

Where plastics accumulate, so do the microbes that colonize them. That means a single weathered bottle cap or a cloud of microbeads can carry a complex, and occasionally harmful, microbial mix to beaches, estuaries, or animal feeding grounds. Marine animals may ingest these bacteria-laden plastics, and people involved in beach clean-ups or recreational activities can come into contact with contaminated items.

Advice for volunteers and coastal managers

"This work highlights the diverse and sometimes harmful bacteria that grow on plastic in the environment," says marine scientist Emily Stevenson of the University of Exeter. Based on the findings, researchers recommend that anyone handling beach litter wear gloves and wash their hands thoroughly after clean-ups.

Beyond personal hygiene, the study underscores the need to prevent plastics from entering ecosystems in the first place — for example by reducing single-use polymers and stopping bio-beads and microbeads from being released.

Practical steps and policy implications

Cleaning beaches is vital, but protocols should be updated: provide gloves and sanitiser to volunteers, treat heavily fouled plastics as contaminated waste, and prioritise campaigns to curb plastic inputs at source. Policymakers and manufacturers should also accelerate alternatives to microplastic-producing products and improve waste-capture systems so fewer microplastics become bacterial hotspots in the wild.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment