4 Minutes

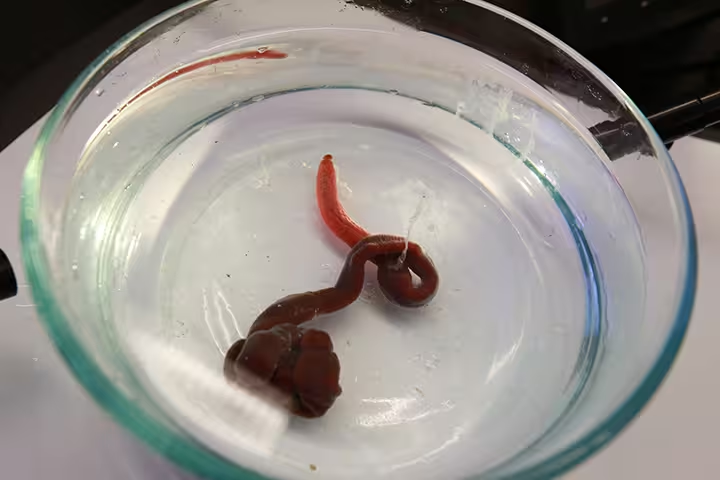

Biologist Jon Allen quietly cares for one of the oldest ribbon worms on record — an adopted invertebrate nicknamed Baseodiscus the Eldest, or just "B." Recent genetic and historical analysis suggest B is at least 26 years old and possibly close to 30, far older than any previously documented member of the phylum Nemertea.

A surprising long-liver from the mud

When stretched out, B reaches roughly a meter (about 3 feet). That length is striking, but the real headline is lifespan: ribbon worms are common across marine environments, yet their natural longevity has been largely unknown. In fact, before B, the longest-documented ribbon worm in the scientific literature was just three years old — making this discovery a dramatic jump in our understanding of nemertean lifespans.

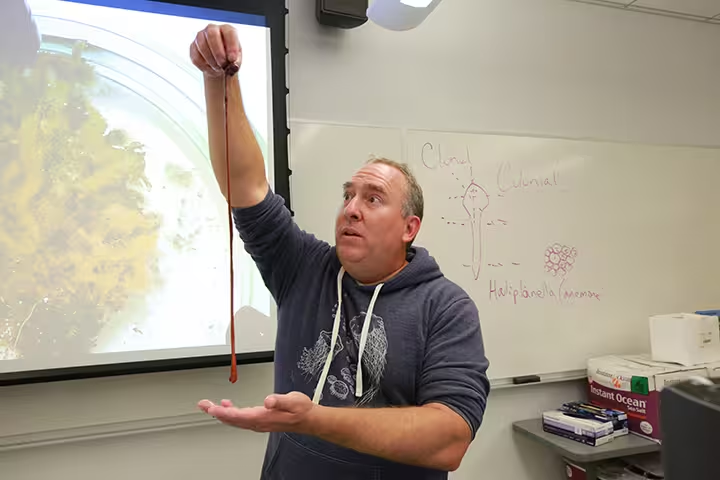

Jon Allen began housing B in a tank filled with mud in 2005 after rescuing the worm from the University of North Carolina during renovations. Researchers believe B was collected as an adult in the late 1990s from the San Juan Islands, which places the animal's likely age near three decades.

Genetic sleuthing and species ID

In 2024 a former student persuaded Allen to run genetic tests. Results identified the animal as Baseodiscus punnetti — only the second individual of that species to be genetically barcoded. Genetic barcoding helps confirm species identity using a short DNA sequence; in this case it anchored B's identity within Nemertea and provided a clearer context for lifespan estimates.

Over the past two decades, B has been a traveler: from Washington state to North Carolina to Maine and now to Virginia, moving with Allen as he taught and worked. The worm’s journey highlights how small collections and academic labs can unexpectedly preserve valuable biological records.

Why the age matters for marine ecology

Marine invertebrates include some of the planet's longest-lived animals — deep-sea tube worms can survive for centuries — but scientists knew surprisingly little about long-term dynamics in many shallow-water benthic predators. Ribbon worms are active predators on the seafloor; if individuals routinely live decades, their ecological roles and population dynamics must be reassessed.

"Ribbon worms are an incredibly diverse and widespread phylum, yet almost nothing is known about their natural longevity," Allen and his colleagues note. Extending nemertean lifespans by an order of magnitude changes how we model food-web interactions and the stability of benthic communities.

Historical extremes and unanswered questions

Length and lifespan are not the same, but nemerteans have surprised observers before. A famously washed-up ribbon worm collected in Scotland in 1864 was reported to have been extraordinarily long — possibly twice the length of a blue whale when fully extended — though its age remains unknown. Such anecdotes underscore how little we understand about growth, regeneration and longevity in these soft-bodied animals.

B’s story suggests marine worms could offer new insights for longevity research. Better lifespan estimates for nemerteans will help ecologists assess how long-lived predators affect benthic ecosystems and inform conservation decisions for coastal habitats.

Jon Allen and colleagues published their analysis in the Journal of Experimental Zoology, calling for more systematic lifespan studies across Nemertea to fill this gap in marine biology.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment