5 Minutes

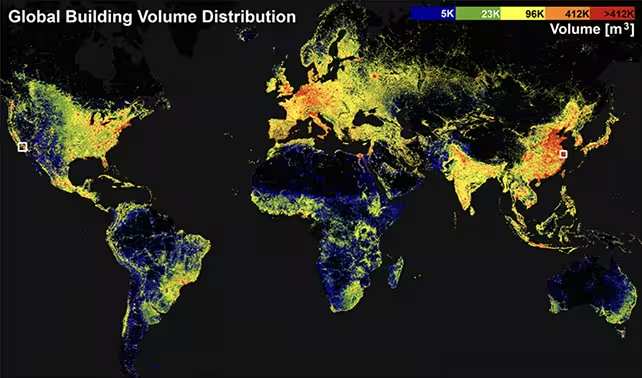

Researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have published the largest three-dimensional map of human-built structures to date: an online GlobalBuildingAtlas that locates and models roughly 2.75 billion buildings across the planet. Built from satellite imagery, height measurements and machine-learning, the atlas offers volumetric insight into urban form at a scale never seen before.

A leap from footprints to volumetric cities

Previous global datasets — such as Microsoft's building footprint database — have focused largely on two-dimensional outlines. The TUM atlas goes further by estimating building heights and producing 3-by-3 meter 3D blocks that describe the approximate shape and volume of nearly every structure. That spatial resolution isn’t fine enough to reveal façade details, but it is roughly 30 times higher in granularity than earlier footprint collections, making it far more useful for measuring the density and vertical scale of urban areas.

Why does volume matter? Because a building’s footprint alone can mislead planners and analysts about how many people live or work in a place. Volume captures the three-dimensional mass — and with it, an improved proxy for population, housing capacity and infrastructure demand. The atlas introduces a novel metric: building volume per capita, which links the total built mass in an area to its population as an indicator of housing availability, socioeconomic differences and urban form.

How the atlas was created

The project relied on a massive archive of satellite imagery combined with measured height samples and machine-learning models that extrapolate heights for regions where direct measurements are sparse. By training algorithms to recognize roof shapes, shadows and contextual cues, the team produced 3D estimates for billions of structures worldwide.

Those AI-driven steps made the project tractable at global scale, but they also introduce known uncertainties. The TUM team acknowledges that high-rise heights are often underestimated and that some regions — particularly parts of Africa — need more local training data and ground validation. Still, the dataset represents a dramatic improvement in both coverage and three-dimensional detail compared with prior resources.

The atlas is publicly available online under the name GlobalBuildingAtlas, and the authors of the underlying study published their methods and validation in Earth System Science Data (2025).

The atlas enabled the researchers to map building density across the globe

Implications for cities, climate and disaster planning

Volumetric building data has immediate applications across several domains. Urban planners can use building volume to estimate population concentration more precisely, helping to plan schools, hospitals and transit. Disaster managers can better model exposure and vulnerability by understanding not only where structures sit but how much built mass exists in hazard-prone areas. Climate scientists and policy teams can incorporate urban volume into models of energy demand, heat islands and emissions associated with buildings.

As the United Nations pursues Sustainable Development Goal targets for inclusive, safe and resilient cities, improved 3D data provides a more accurate view of urban inequality and infrastructure needs. Building volume per capita, for example, can reveal disparities in housing density and investment that 2D maps obscure.

Limitations, validation and future improvements

No global machine-generated map is perfect. The TUM team highlights regional biases where training data are limited, systematic underestimation of very tall buildings, and the usual challenges of satellite-derived products — cloud cover, seasonal differences and mixed land uses. The atlas is explicitly framed as iterative: additional ground surveys, more diverse training samples and improved algorithms will refine heights and reduce regional error.

Open availability is a strength here: as more researchers and local authorities use and validate the dataset, errors can be identified and corrected, and the atlas can become a shared foundation for urban research and policy.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Marquez, an urban geospatial scientist not involved with the project, notes: 'This atlas is a major step forward because it changes the unit of analysis from flat footprints to true three-dimensional urban fabric. Even with current uncertainties, volume-based metrics let us ask better questions about housing, services and resilience. The next advance will be integrating local census and building-use data to translate volume into functional outcomes — who lives where and why.'

Looking ahead, the GlobalBuildingAtlas promises to be a powerful platform for interdisciplinary work: satellite and AI developers can improve detection and height inference; urbanists and demographers can test new population models; and policy-makers can ground funding decisions in a clearer portrait of built environments.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

mechbyte

Sounds impressive, but how reliable is the AI height estimation in crowded skylines? underestimation of very tall towers seems like a big caveat. Any local validation data?

geoNix

Wow 2.75 billion buildings, that's wild. Volume over footprints actually changes the game for cities, but curious how they correct high-rise underestimates, hmm

Leave a Comment