3 Minutes

An international analysis of nearly 30,000 brain scans finds links between frequent consumption of ultra-processed foods and subtle structural changes in the brain—changes that could help explain persistent cravings and overeating.

What the scans revealed

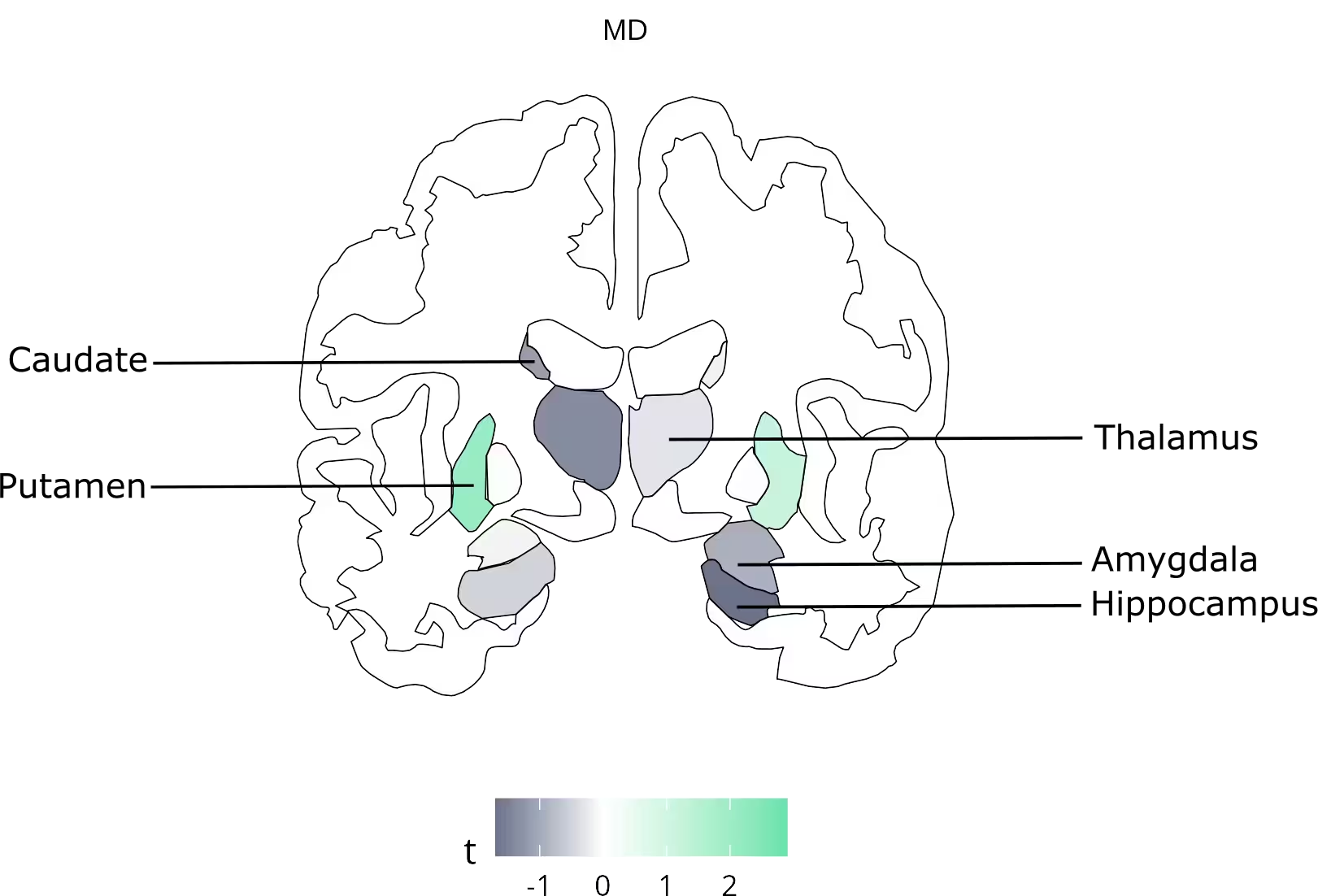

Researchers tapped the large UK Biobank dataset to compare dietary questionnaires with MRI-based measures of brain tissue. The study identified regional differences in brain cell density among people who reported higher intake of ultra-processed foods (UPFs). Some grey-matter regions showed lower cell density, a pattern that can indicate neuronal loss or degeneration; other areas displayed increased cell density that may reflect local inflammation.

This image shows brain areas linked to high consumption of ultra-processed foods. The grey regions indicate lower cell density, which may suggest a loss of brain cells—a possible sign of brain degeneration. The green regions show higher cell density, which could reflect inflammation in the brain. Credit: Image provided by the study authors

The study does not prove cause and effect, but the associations remained after accounting for body mass index and markers of systemic inflammation. "Our findings suggest that higher consumption of ultra-processed foods is associated with differences in the brain," said Arsène Kanyamibwa of the University of Helsinki, one of the study's lead authors. He emphasized that while the imaging links could help explain overeating behaviour, longitudinal or experimental work is needed to establish causal mechanisms.

Why additives like emulsifiers are under scrutiny

Unlike minimally processed items—such as frozen vegetables or pasteurised milk—UPFs frequently contain industrial additives and chemically modified ingredients. The researchers highlight emulsifiers and other additives as plausible contributors to the observed brain patterns. Laboratory studies and animal experiments have shown that some emulsifiers can alter gut microbiota and promote low-grade inflammation; this gut–brain dialogue is one possible pathway linking diet to brain structure.

Still, the imaging signal is unlikely to be explained by a single factor. Genetics, lifestyle, socioeconomic status and co-occurring health conditions can all influence brain health. The novel contribution of this work is the scale: nearly 30,000 participants give statistical power to detect subtle associations that smaller studies might miss.

Implications for diet, public health and regulation

For consumers, the message is nuanced. Many processed foods are safe and practical—frozen vegetables and pasteurised dairy can be beneficial—but products engineered with multiple additives, artificial flavours, and long ingredient lists are where concerns concentrate. The study's authors argue that reducing UPF intake could be a sensible public-health recommendation while regulators consider stronger standards for food manufacturing.

Practical steps

- Prioritise whole and minimally processed foods where possible.

- Read ingredient lists—shorter lists usually mean fewer industrial additives.

- Support policies that limit ultra-processed food marketing and require clearer labelling.

As the evidence base grows, these imaging findings strengthen calls for more research into how modern diets influence the brain and behaviour. Policymakers and health professionals may increasingly view UPFs not only as a metabolic risk, but also as a factor relevant to brain health and eating regulation.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment