6 Minutes

New laboratory work suggests that reducing a single essential amino acid in the diet—isoleucine—can slow aging and increase lifespan in mice. The finding raises questions about whether targeted amino-acid interventions could improve human longevity and healthspan, but translating mouse results to people will require careful study.

Why one amino acid became the focus of longevity research

Isoleucine is one of three branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) our bodies use to build proteins and maintain tissues. Because humans cannot synthesize isoleucine internally, we obtain it from protein-rich foods such as eggs, dairy, soy, and meats. That biochemical necessity makes it both essential and, potentially, a lever for metabolic change.

Researchers have been aware for some time that not all calories are equal—individual nutrients can change metabolism and health beyond their simple caloric value. A 2016–2017 survey of Wisconsin residents previously found an association between higher dietary isoleucine intake and worse metabolic measures, particularly in people with higher body mass indices. That suggested isoleucine intake might relate to obesity and metabolic dysfunction, prompting deeper experimental work in animals.

A controlled mouse experiment that isolated isoleucine

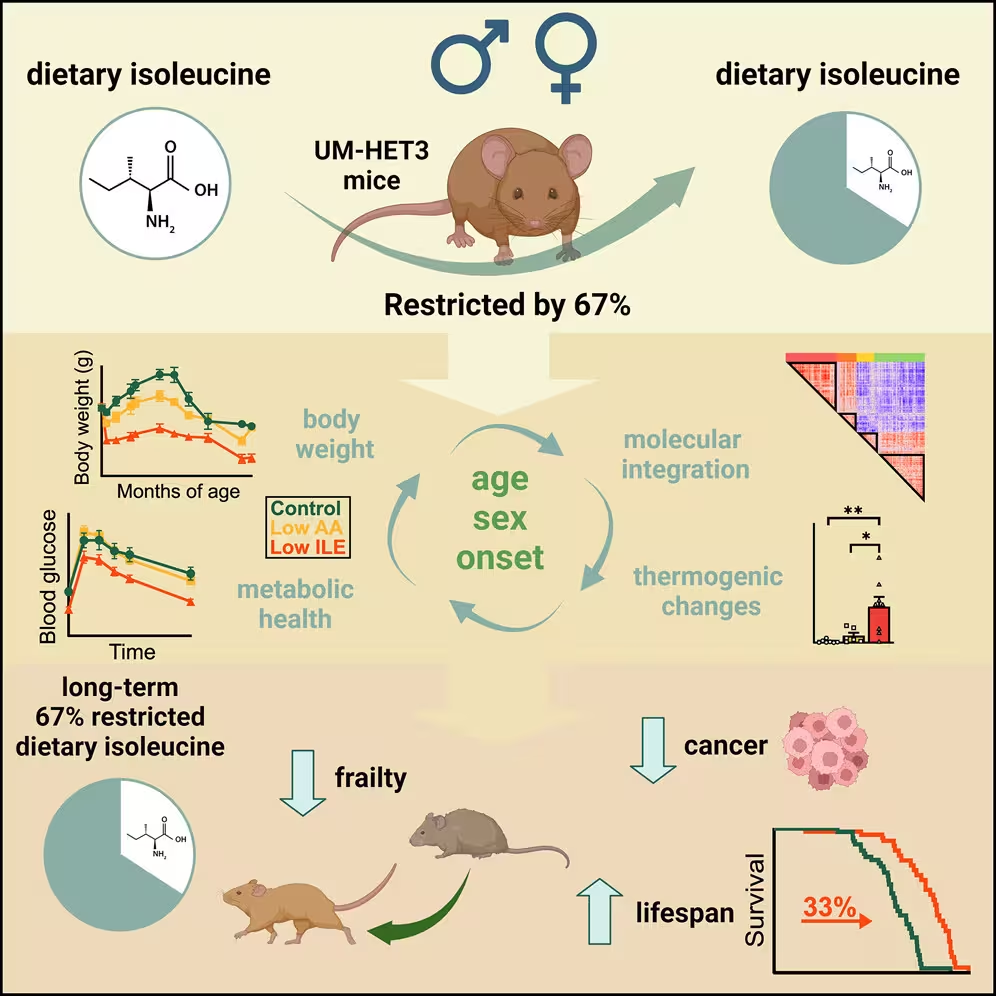

To test how isoleucine affects aging, scientists fed genetically diverse mice one of three diets: a control diet with the usual 20 common amino acids; a diet in which all amino acids were reduced by roughly two-thirds; or a diet where only isoleucine was reduced by the same two-thirds amount. The study started when mice were about six months old—roughly equivalent to a 30-year-old human—and animals could eat freely from their assigned food.

Instead of simple calorie restriction, this experiment isolated a single nutrient variable. Endocrinologist Dudley Lamming of the University of Wisconsin, involved in these studies, has emphasized that “a calorie is not just a calorie”—the composition matters. By narrowing in on isoleucine, researchers hoped to tease apart which dietary components drive aging-related changes.

Key findings: longer life, better health markers

Restricting dietary isoleucine produced striking benefits in mice. Male mice on the low-isoleucine diet lived about 33% longer than controls; females showed roughly a 7% increase in median lifespan. Beyond survival, animals on the restricted isoleucine diet performed better across 26 health measures, including muscle strength, endurance, blood-sugar regulation, tail use, and reduced hair loss. Male mice also showed less age-related prostate enlargement and a lower incidence of the common tumors found in these genetically diverse strains.

Curiously, mice given low-isoleucine food actually consumed more calories than the other groups. Rather than gaining weight, they burned more energy, lost fat, and maintained leaner body composition without increasing physical activity. As Lamming noted, the mice quickly lost adiposity and became leaner despite eating more.

These results suggest isoleucine restriction alters metabolic set points—shifting the body toward higher energy expenditure and better glycemic control. The study was published in Cell Metabolism and builds on the idea that adjusting specific dietary amino acids, rather than total calories or total protein alone, can influence aging biology.

How this might translate to humans—and why caution is needed

Mouse studies provide essential mechanistic insight, but human diets and physiology are more complex. The researchers caution that simply cutting back on high-protein foods is not a reliable or safe prescription. Widespread reduction of protein can harm growth, immunity, and other functions; the balance and timing of amino-acid intake matter.

The authors also highlight that diet is a chemical network—altering one component can change many downstream pathways. The study used a precise reduction of isoleucine in a controlled feed; in real-world human diets, other nutrients and lifestyle factors will interact with any change in amino-acid intake.

Still, the concept of targeting a single amino acid is appealing for drug development. If the biological benefit stems from specific signaling pathways activated by low isoleucine, pharmacological blockers or modulators might mimic those effects without risking protein deficiency. Lamming said the findings bring researchers “closer to understanding the biological processes and maybe potential interventions for humans, like an isoleucine-blocking drug.”

Biological background: branched-chain amino acids and aging

BCAAs—leucine, isoleucine and valine—play roles in muscle synthesis, energy balance and signaling pathways such as mTOR that link nutrient status to cellular growth. Overactivation of nutrient-sensing pathways has been implicated in aging; restricting specific amino acids can dampen these signals and produce benefits similar to calorie restriction in experimental organisms.

Understanding which amino acids influence mTOR and related pathways, and how those effects vary by sex and genetic background, is critical. In the mouse study, males and females responded differently—indicating that optimal intervention may require sex-specific tuning and consideration of genetic diversity.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Rivera, a fictional but realistic aging biologist and science communicator, comments: "This study is an elegant proof-of-concept that single-nutrient interventions can shift whole-body metabolism and aging trajectories. The metabolic improvements and extended survival, especially in males, tell us that targeted nutrient signaling—not just caloric load—can be a powerful lever. Translating this to humans will require careful dose-response studies, long-term safety data, and attention to life stage and sex differences."

Next steps: trials, drugs and dietary patterns

Future work will need to test whether similar interventions are safe and effective in people. Short-term human trials could evaluate metabolic endpoints—insulin sensitivity, fat mass, muscle function—before any long-term longevity studies. Parallel drug-discovery efforts could aim for molecules that selectively mimic low-isoleucine states, targeting relevant signaling nodes without causing essential amino-acid deficiency.

Practical dietary guidance may also emerge: choosing protein sources with lower isoleucine content or shifting meal timing might modestly lower isoleucine exposure while preserving overall protein adequacy. But until human data exist, the most prudent advice is to follow balanced, evidence-based dietary patterns and watch for new clinical trials testing these ideas.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

mechbit

Wait so male mice lived way longer but females barely, is that even reliable? Diet tweaks in mice are tricky, plus what about muscle loss in humans? idk, seems premature

geneFlux

wow this blew my mind, tho kinda freaky. If one amino acid can flip metabolism.. curious but worried about side effects, esp in ppl. Where's the human data?

Leave a Comment