6 Minutes

Researchers at MIT and Stanford have developed a fresh immunotherapy approach that disables a sugar-based molecular “brake” on cancer cells, allowing the immune system to detect and destroy tumors that previously slipped past immune surveillance. The strategy uses engineered hybrid proteins called AbLecs — lectin-linked antibodies — to block glycan-mediated signals that suppress immune activity.

Why glycans matter: the hidden sugar signals on cancer cells

Glycans are complex sugar structures coating nearly every cell in the body. Cancer changes this sugary coat: tumor cells often display unusual glycans rich in sialic acid. Those sialic-acid–bearing glycans engage lectin receptors on immune cells, known as Siglecs, and activate an immunosuppressive pathway that acts like a brake on anti-tumor responses.

Current checkpoint inhibitors — the drugs that block PD-1 or PD-L1 — release one class of brakes and have delivered dramatic, durable remissions in some patients. But many tumors resist these therapies. The Siglec–sialic acid axis represents an alternative checkpoint: when Siglecs bind sialic acids on cancer cells, macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, and other immune effectors are less likely to attack.

How AbLecs work: hijacking lectins with antibodies

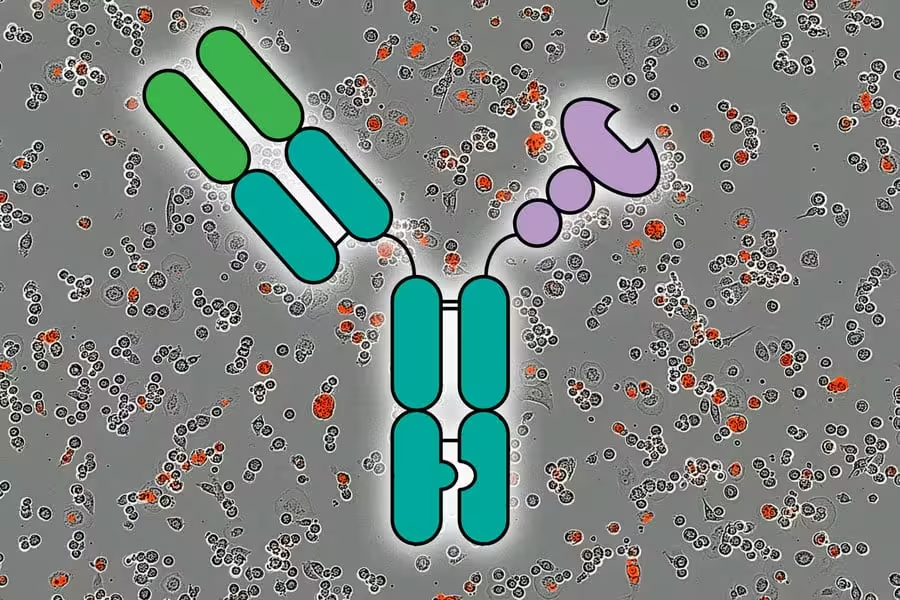

The central innovation from the MIT and Stanford teams is a modular protein they call an AbLec. Each AbLec fuses a lectin-like domain that binds sialic-acid glycans to an antibody arm that recognizes a tumor-specific antigen. The antibody delivers and concentrates the lectin domain on the tumor cell surface, where it competes with immune-cell Siglecs for sialic-acid binding.

From weak binder to effective blocker

Lectin domains by themselves tend to bind weakly and do not accumulate effectively on tumors. By contrast, antibodies have high affinity for tumor antigens and can localize to cancer cells in large numbers. Linking a lectin to an antibody combines the strengths of both: targeted delivery plus local glycan blockade. The result is a locally concentrated decoy that prevents immune-suppressive Siglec engagement and frees immune cells to attack.

Researchers showed they could stimulate a strong anti-tumor immune response by using molecules called AbLecs, represented here in center, that block an immune checkpoint. The background shows red fluorescence which indicates killed cancer cells over a period of 5 hours. Credit: Courtesy of the researchers; MIT News

Preclinical evidence: from cells to humanized mice

To demonstrate proof of concept, the team built an AbLec using trastuzumab (the anti-HER2 antibody) with a lectin domain derived from Siglec-7 or Siglec-9. In cell-based assays, those AbLecs reprogrammed immune cells to attack HER2-positive tumor cells. In a mouse model engineered to express human Siglecs and human antibody receptors, treatment with the AbLec reduced lung metastases relative to trastuzumab alone.

These results are important because they show both innate immune effectors (like macrophages and NK cells) and adaptive responses can be liberated by blocking glycan-based checkpoints. The approach reduced tumor burden in settings where standard antibody therapy had a more limited effect.

Modular design: a plug-and-play platform

One of the most promising aspects of AbLecs is modularity. The antibody arm can be swapped to target different tumor antigens — for instance, rituximab (CD20) for B-cell cancers or cetuximab (EGFR) for other solid tumors. Likewise, the lectin domain can be swapped to target distinct glycans or members of the lectin receptor family. This plug-and-play design opens possibilities for cancer-specific customization and combination therapies.

Because many tumor types rely on glycan-based immune suppression, AbLecs could complement existing checkpoint inhibitors or serve patients who don’t respond to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. They are also adaptable to target multiple immunosuppressive glycan motifs that emerge in different cancers.

Challenges and next steps

Important hurdles remain before AbLecs reach the clinic. Tumor-associated glycans are sometimes expressed, at lower levels, on healthy tissues — raising questions about off-target effects and safety. The immune system itself can react to new protein constructs, so immunogenicity and dosing strategies must be rigorously tested. Manufacturing complex hybrid proteins at scale is another real-world challenge.

Crucially, translation requires human clinical trials to evaluate efficacy, tolerability, and whether AbLecs truly expand the population of patients who benefit from immunotherapy. The preclinical results justify that next step, but only carefully designed trials will determine clinical value.

Expert Insight

"Targeting the glycan landscape is an elegant way to broaden immunotherapy," says Dr. Elena Morales, an immuno-oncologist not involved with the study. "AbLecs cleverly solve a delivery problem — they turn weak glycan binders into potent, tumor-localized blockers. If safety and specificity hold up in trials, this could become an important complement to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors."

Implications for patients and therapies

For patients, AbLec technology promises two major potential advantages: first, the ability to overcome a previously untargeted immune-evasion mechanism; second, the flexibility to be tailored to different tumor antigens and glycan targets. That means, in principle, a wider fraction of cancers could become responsive to immunotherapy.

In practical terms, clinicians and researchers will need to define biomarkers that predict which tumors are driven by sialic-acid–Siglec interactions. Patient selection, combination regimens, and safety monitoring will determine how AbLecs are deployed alongside existing treatments.

Looking ahead

The AbLec strategy illustrates a broader trend in cancer immunology: targeting the tumor microenvironment’s biochemical signals, not only immune-cell checkpoints. By converting molecular decoys into targeted therapeutics, scientists aim to unmask cancer to the immune system in new ways. The next chapters will be written in early clinical trials, where efficacy, safety, and real-world impact will be tested.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Tomas

Is this even specific enough? Tumor glycans are on normal cells too, off-target toxicity seems likely. curious how they'll pick biomarkers, dosing etc

atomwave

Whoa turning sugars into a key to unlock immune attack? Wild idea, actually kinda hopeful. If it works in ppl tho… safety worries, but clever!!

Leave a Comment