6 Minutes

HPV vaccination programs that ignore males risk prolonging a preventable public health crisis. New modeling from the University of Maryland shows that extending HPV immunization to boys could be the missing piece in efforts to eliminate cervical cancer and other HPV-related cancers worldwide. Here’s what the simulations reveal, why boys matter, and how policy could pivot to accelerate elimination.

Why vaccinating boys changes the math

Human papillomavirus, or HPV, is highly contagious. It spreads through sexual contact and even through skin-to-skin exposure, and it is the primary cause of cervical cancer, plus a range of other malignancies including anal, penile, and certain head and neck cancers. Globally, cervical cancer still kills more than 300,000 people each year, despite the availability of highly effective vaccines.

The first HPV vaccine was licensed in 2006 and was initially promoted as a women’s preventative measure to reduce cervical cancer. That campaign worked: in many places cervical cancer incidence has fallen dramatically. But the original, gendered rollout left a gap. Today we know that both men and women are vulnerable to HPV-related cancers, and that vaccinating only half the population may be insufficient to interrupt transmission of the high-risk viral strains.

Mathematical models make this clear. When immunization focuses narrowly on girls and women, herd immunity thresholds become much higher for females alone. As Abba Gumel, lead author and mathematician, puts it, "Vaccinating boys reduces the pressure of having to vaccinate a large proportion of females. It makes elimination more realistically achievable." In short, including boys eases the coverage burden on females and speeds population-level protection.

Modeling South Korea: a practical test case

Researchers calibrated a new transmission and cancer-progression model using South Korean cancer and vaccination data to test different vaccination and screening strategies. The results are instructive for countries with high female coverage but low male uptake.

The model found that under South Korea's current female-only vaccination program, the nation would need nearly universal immunization among young women — roughly 99 percent — to achieve herd immunity against the cancer-causing HPV strains. At present, female vaccination coverage in South Korea sits around 88 percent, so HPV can still circulate and cause disease.

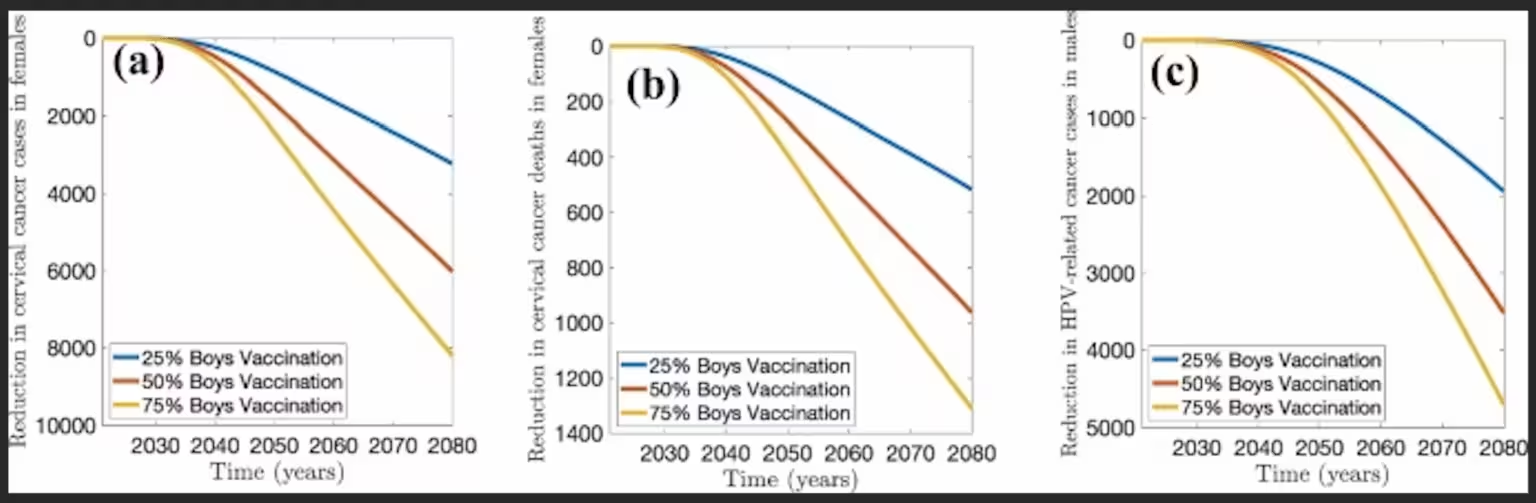

However, if the program were expanded to include boys, the dynamics shift markedly. The team reports that vaccinating 65 percent of boys while holding female coverage steady would move South Korea onto a path to eliminate HPV-related cancers over the coming decades, with modeled elimination timelines on the order of 70 years. If female uptake slipped to 80 percent, elimination could still be reached if roughly 80 percent of males were vaccinated.

The model also tracked male cancer outcomes. Over the last two decades, HPV-related cancers in South Korean men have tripled. By boosting male vaccination rates, the population would not only accelerate cervical cancer elimination in women but also prevent rising morbidity and mortality among men.

What this means beyond South Korea

Although the study is calibrated to South Korean data, the model is portable. Gumel and colleagues suggest that in countries like the United States, balanced vaccination coverage of around 70 percent in both men and women could be sufficient to achieve herd immunity for the major oncogenic HPV strains. Achieving those levels would substantially reduce the future burden of cervical, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers.

Importantly, adding boys to national immunization schedules is not only a preventive measure for future generations. Emerging evidence indicates that vaccinating older adolescents and some adults who missed early vaccination can still provide meaningful protection against infection and disease. That creates an opportunity for catch-up campaigns alongside routine school-based delivery.

Policy levers and public health messaging

Health ministries and immunization advisory bodies can act on several fronts: expand formal recommendations to include boys, implement school-based delivery to increase coverage, and invest in public messaging that frames HPV as a disease affecting everyone. Addressing the lingering gender bias in vaccine policy and communication is essential.

- Include boys in routine adolescent schedules and fund catch-up vaccination for missed cohorts.

- Couple vaccination scale-up with enhanced cervical screening to hasten reductions in cancer incidence.

- Target public education to correct misconceptions that HPV is only a women’s issue.

By combining higher vaccination coverage across both sexes with continued investment in screening and early detection, countries can make elimination realistic. Some estimates suggest that with broad vaccination and screening expansion, cervical cancer could be eliminated in roughly 149 of 181 countries by the end of the century.

Expert Insight

Dr. Lina Morales, an infectious-disease epidemiologist and science communicator, commented on the findings: "Models like this translate complex biology and population behavior into clear targets for policy. Vaccinating boys is not just about equity. It is a practical, evidence-based lever that reduces transmission and makes elimination achievable. When programs are designed for the whole population, everyone benefits."

Gumel’s team concludes with a stark reminder: we are not powerless against HPV. With improved vaccine coverage across both sexes, and sensible screening policies, the annual toll of roughly 350,000 cervical cancer deaths can be dramatically reduced — and, in many countries, eliminated in the long term.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Marius

Finally! vaccinate boys too, makes sense and can really speed elimination. Saves lives, evens the burden. Hope policy folks act, pronto

labQuark

hmm interesting model but is 70 yrs realistic? assumptions about sexual behavior and waning immunity matter, plus politics, cost and uptake, will they actually fund it?

Leave a Comment