7 Minutes

Fossils have long told us about bones, teeth and the shapes of extinct creatures. Now they are revealing something less obvious and far more intimate: the chemical traces of metabolism frozen inside ancient bone. By extracting metabolites from million-year-old specimens, researchers can reconstruct diet, disease, and the local climate with a new level of precision.

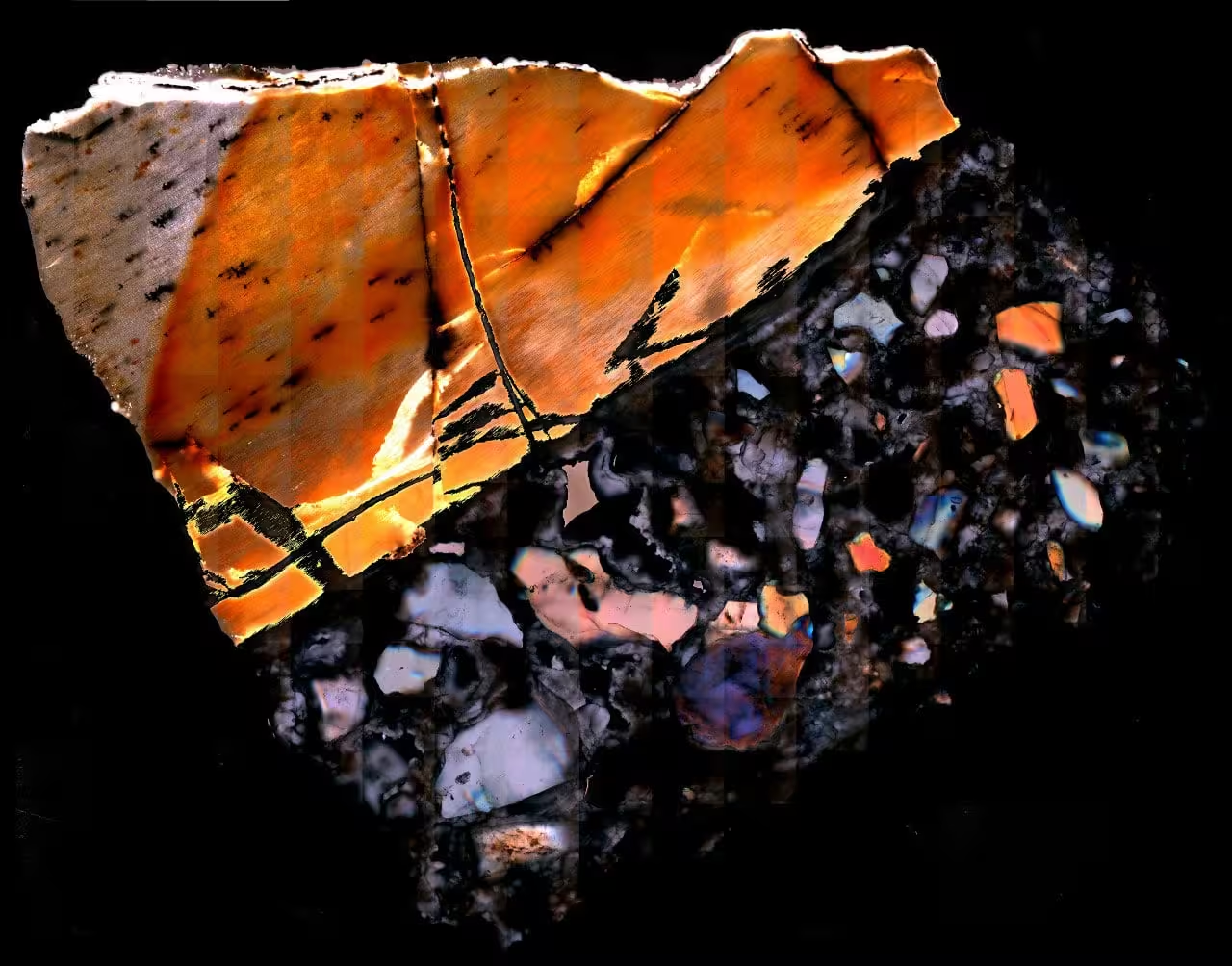

Fossilized elephant dentine (scale: 1.5 mm across), with rock seen in the lower right and dentine in the upper left. The white dentine is intact collagen. Credit: Timothy Bromage and Bin Hu, NYU Dentistry

A new window into ancient life

For decades, paleontology has relied on bones, teeth and, more recently, ancient DNA to piece together evolutionary stories. DNA is powerful for ancestry, but it tells only part of the tale. Metabolites — small molecules produced by metabolism, such as amino acids, sugars, vitamins and signaling compounds — record an organism's physiological state at the time of death. These molecules can reflect what an animal ate, the diseases it fought, and even the temperature and moisture of its environment.

Until now, metabolomic methods were mostly restricted to living organisms and recent remains. A team led by Timothy Bromage at New York University asked a simple but bold question: if collagen and some proteins can survive for millions of years, could the microenvironment inside bone also preserve metabolic molecules? Their results, published in Nature, suggest the answer is yes.

How researchers pulled molecules from million year old bone

The study combined careful sampling of well-dated fossils with high-resolution mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry works by ionizing molecules and measuring their mass to charge ratios, enabling researchers to identify thousands of chemical species in a single sample. To build a reference, the team first analyzed modern mouse bones and catalogued nearly 2,200 metabolites and associated proteins including collagen.

Olduvai Gorge, an important archaeological site in northern Tanzania. Credit: Friedemann Schrenk, Goethe University and Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum

Armed with that reference, the researchers analyzed fossil bone fragments from sites across eastern and southern Africa, including Tanzania, Malawi and South Africa. The fossils ranged from roughly 1.3 to 3 million years old and came from animals that still have living relatives near those sites: small rodents like mice, ground squirrels and gerbils, plus larger species including antelope, pig and elephant.

Remarkably, thousands of metabolites were detected in the fossil bones, and many matched compounds found in living animals. That overlap makes it possible to interpret fossil metabolite signatures in biologically meaningful ways rather than as ambiguous chemical noise.

What the molecules reveal about diet, disease and climate

Some metabolites reflected standard physiological processes such as amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism. Others pointed to sex hormones, enabling inferences about the biological sex of certain individuals. Several signatures were unmistakably linked to disease. In one striking example, the bone of a 1.8 million year old ground squirrel from Olduvai Gorge carried a metabolite unique to a parasite related to Trypanosoma brucei, a pathogen that causes sleeping sickness in humans and other mammals. The team also identified metabolites consistent with the squirrel mounting an anti inflammatory response to infection.

Dietary traces were equally informative. The researchers detected plant metabolites associated with regional flora, including variants tied to aloe and asparagus. Those compounds provide ecological clues: aloe tends to indicate particular soil, rainfall and canopy conditions. If a ground squirrel carried aloe metabolites, then the local environment likely supported that plant, helping reconstruct microhabitats from millions of years ago.

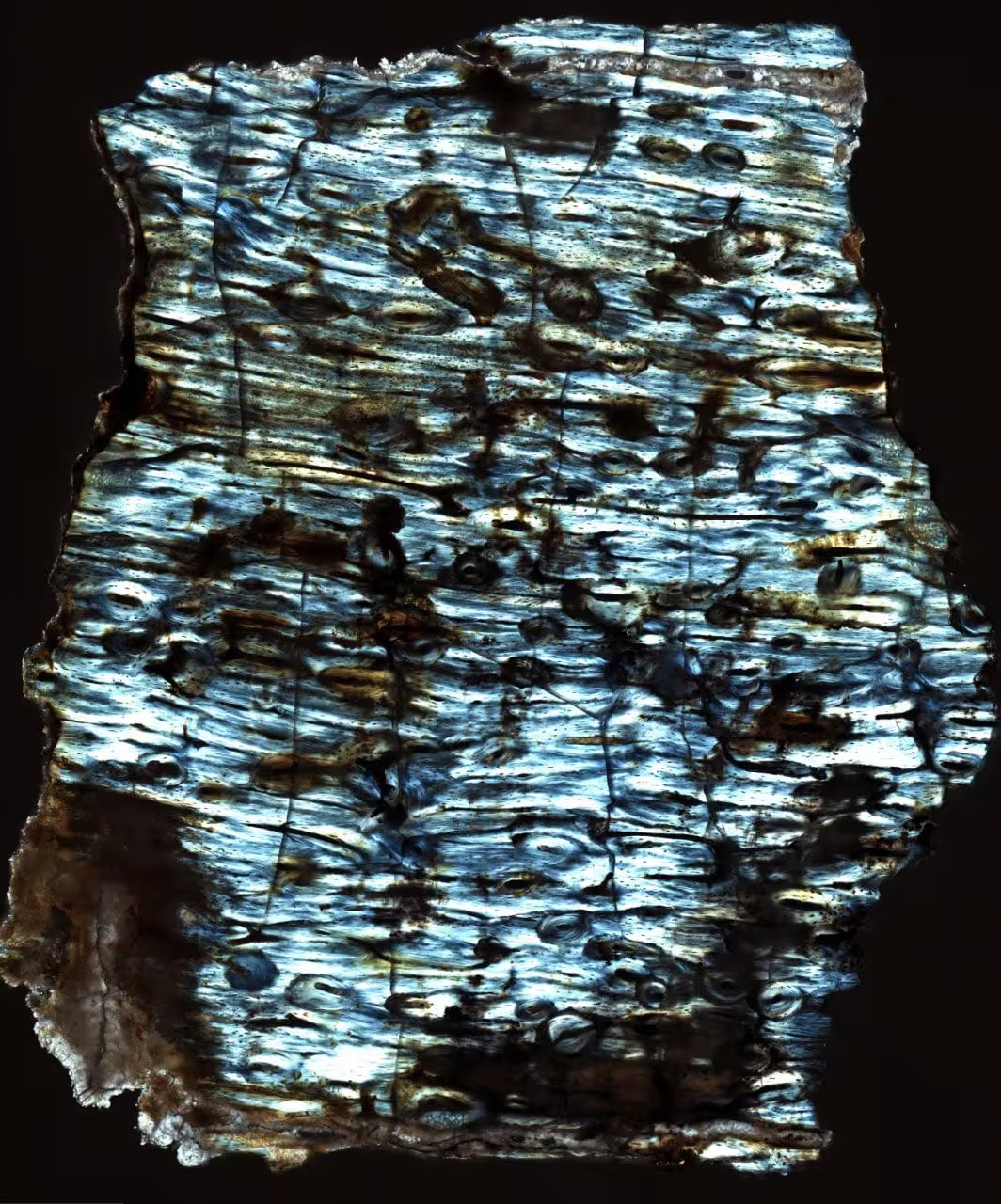

A polarized light image of fossilized antelope bone showing intact collagen (scale: 1 mm across) Credit: Timothy Bromage and Bin Hu, NYU Dentistry

Across the examined sites, metabolomic reconstructions supported previous paleoecological work indicating that landscapes were generally warmer and wetter in the past than they are today. For example, layers at Olduvai correspond to freshwater woodland and grassland transitioning to drier woodlands and marsh, patterns that align with the metabolite evidence for plant communities and moisture availability.

Why bones can preserve metabolic snapshots

Bones are surprisingly good at protecting chemistry. As they form, porous microstructures and tiny vascular networks create microenvironments where molecules from circulating blood can become trapped. Collagen, the structural protein in bone, can survive deep time and may act as a shield, limiting exposure to oxygen and microbes and slowing degradation. The new work implies that metabolites lodged in these protected pockets can remain detectable on million year timescales under the right conditions.

That said, preservation is complex and variable. Soil chemistry, temperature, burial depth and time all influence which molecules survive. The study used careful contamination controls and comparative modern datasets to distinguish endogenous metabolite signals from later environmental inputs. Future work will refine these protocols and help map when and where paleometabolomics is most reliable.

Implications for paleoecology and archaeology

Paleometabolomics opens several new research pathways. By linking metabolism to environment, scientists can ask questions previously out of reach: Were certain fossil populations stressed by drought or disease? Did seasonal dietary shifts leave signatures in bone chemistry? How did microhabitats at key archaeological sites influence hominin behavior and survival?

This approach complements ancient DNA and isotopic studies rather than replacing them. Together, these tools can deliver a richer, more nuanced reconstruction of past ecosystems, blending genetic history with physiological state and ecological context.

Expert Insight

— Dr. Jane Thompson, paleoecologist at an independent research institute, on the study's significance: This work adds a new dimension to how we read the fossil record. It is like finding a diary inside bone that records short term events such as diet choices and disease episodes. While the method needs broader testing across environments and ages, its potential for refining paleoecological reconstructions is enormous.

Looking ahead, researchers aim to expand reference databases, test older samples and evaluate preservation limits. Improved mass spectrometry and micro sampling techniques will make it possible to target specific bone microenvironments, reducing contamination risks and enhancing the resolution of metabolite maps.

Paleometabolomics promises not only to rewrite details about extinct animals, but to reconstruct the landscapes they inhabited with ecological fidelity comparable to modern field studies. Imagine walking into a million year old ecosystem through the chemical footprints left in bone — a combination of diet, disease and climate rendered in molecular detail.

The antelope bone fragment in rock that guided this new approach demonstrates how a single fossil can yield multiple lines of evidence, bridging anatomy, chemistry and environment. As methods mature, similar analyses could illuminate the lives of many extinct species and the changing worlds they lived in.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

skyspin

if that's real then wow, but how do they separate ancient metabolites from modern contamination? need clearer controls, samples, stats pls

bioNix

wow didn’t expect chemicals to survive millions yrs, this feels like opening a time capsule.. curious but a bit creeped out, ngl

Leave a Comment