9 Minutes

A team of engineers at MIT has developed a 3D-printable aluminum alloy that withstands high temperatures and reaches strength levels up to five times greater than conventionally cast aluminum. Using machine learning to guide alloy design and laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) to fabricate samples, the researchers produced a material with a dense, nanoscale microstructure that holds promise for aerospace, automotive, and data-center cooling applications.

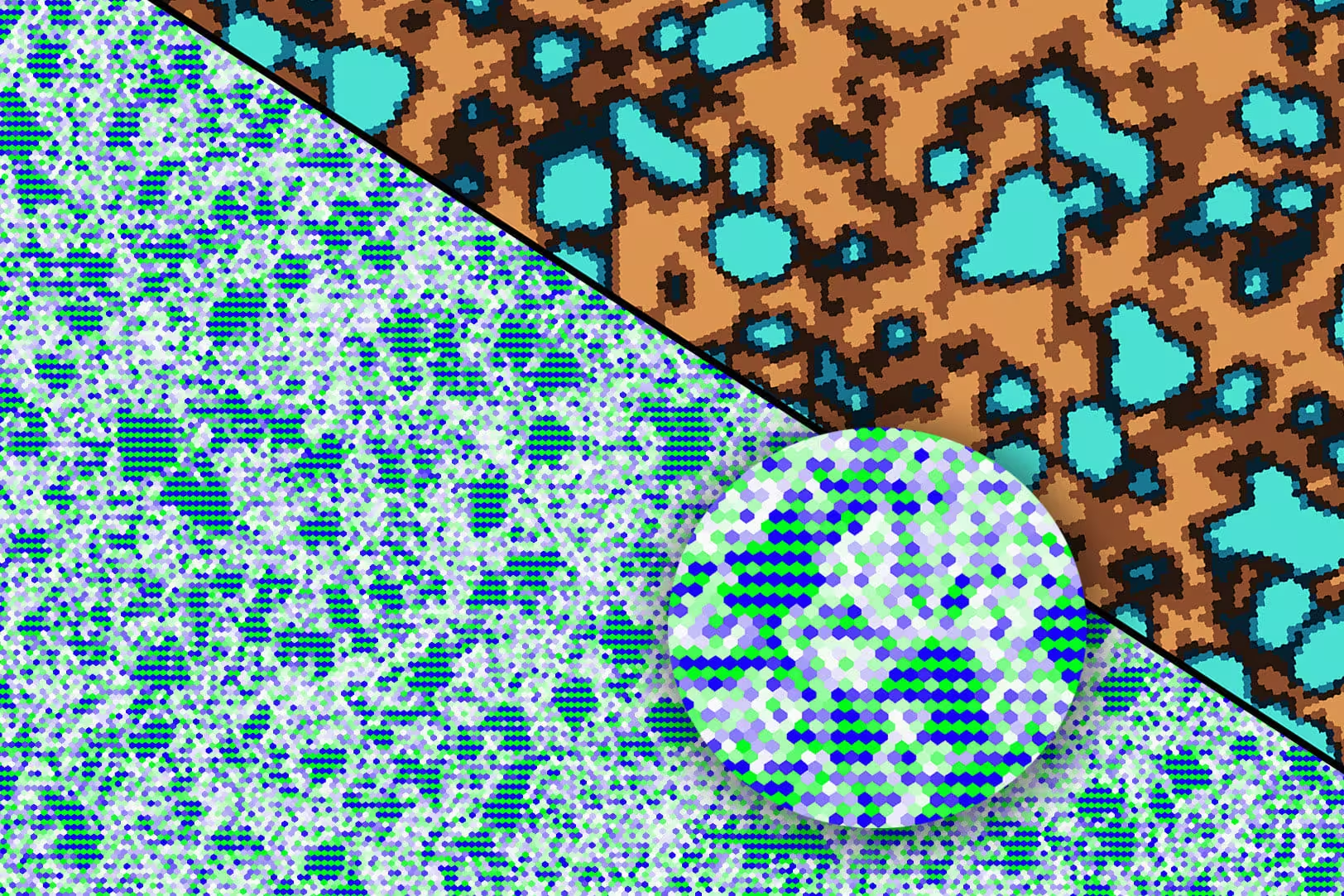

A new 3D-printed aluminum alloy is stronger than traditional aluminum, due to a key recipe that, when printed, produces aluminum (illustrated in brown) with nanometer scale precipitates (in light blue). The precipitates are arranged in regular, nano-scale patterns (blue and green in circle inset) that impart exceptional strength to the printed alloy.

How machine learning shortened a monumental search

Designing a high-performance alloy normally requires exploring vast combinations of elements and concentrations. Instead of simulating more than a million potential mixes, the MIT team used targeted machine-learning models to narrow the search to just 40 candidate compositions. This dramatic reduction let them focus experimental and printing resources on the most promising recipes — a major time and cost saver in materials discovery.

Postdoctoral researcher Mohadeseh Taheri-Mousavi (now at Carnegie Mellon University) led the project after her experience in an MIT materials-design class. The class exercise had already revealed how important microscopic features — especially tiny, densely packed precipitates — are for strengthening aluminum. But traditional simulations struggled to predict which combinations of alloying elements would produce the needed nanoscale microstructure. Machine learning detected non-linear relationships among element properties and pointed researchers toward a composition predicted to produce a high volume fraction of small precipitates when rapidly solidified.

Why 3D printing makes the difference: rapid cooling and microstructure control

The choice of manufacturing method was crucial. In conventional casting, molten aluminum cools relatively slowly and precipitates have time to grow. Those larger precipitates correlate with lower strength. Additive manufacturing — specifically laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) — melts thin powder layers with a laser, producing extremely rapid cooling and solidification. That rapid freezing locks in a fine precipitate structure and prevents coarsening, allowing the alloy’s engineered nanoscale features to survive.

John Hart, head of MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, emphasized that LPBF’s unique thermal profile opens new doors for alloy design: the laser-induced, layer-by-layer melting and solidification produces microstructures that are difficult or impossible to obtain with casting. The team leveraged that capability: machine learning recommended compositions optimized for LPBF’s cooling rates, and the printing process delivered the predicted microstructure.

From simulation to printed sample: testing a new printable alloy

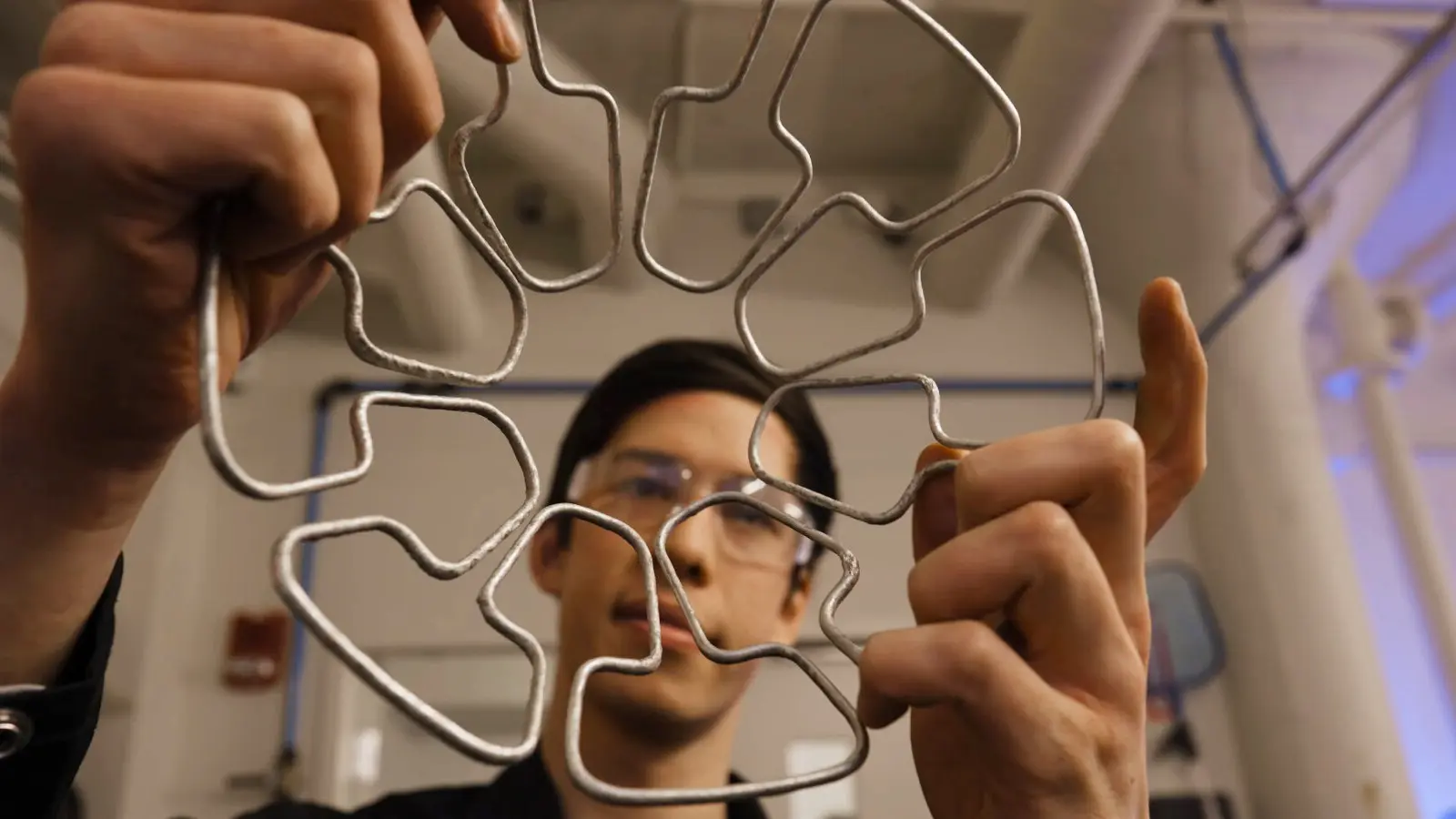

After the algorithm identified a top candidate, the team ordered powder formulated with aluminum plus five other elements and sent it to collaborators in Germany who operated an LPBF system. Printed specimens came back to MIT for mechanical testing and microscopic imaging. Tests confirmed the predictions: the printed alloy was about five times stronger than a comparable casted alloy and roughly 50% stronger than alloys produced from conventional simulation-driven design.

Detailed microstructural analysis showed a much higher volume fraction of tiny precipitates, stable up to roughly 400 °C — a high temperature for aluminum-based materials. That thermal stability, combined with the strength gains, suggests practical use cases where both weight savings and heat resistance matter.

Potential applications: lighter engines, cooler data centers, and beyond

The team envisions replacing heavier, costlier materials in some demanding roles. Jet-engine fan blades, for instance, are often cast from titanium — a metal that can be more than 50% heavier and up to an order of magnitude more expensive than aluminum. If certain components could be made from a lighter, printable alloy that meets performance and temperature requirements, the transportation and aerospace industries could see significant fuel and cost savings.

Other potential uses include advanced vacuum pumps, high-performance automotive parts, and thermal-management components for data centers. Because additive manufacturing enables complex geometries and material-efficient designs, designers could combine topology optimization with the new alloy’s mechanical properties to create parts that are both lighter and stronger than current alternatives.

Scientific context: precipitates, microstructures, and alloy design

Alloys gain strength from microscopic inhomogeneities called precipitates — tiny regions of a different composition that hinder the motion of dislocations (defects in the crystal lattice that mediate plastic deformation). The finer and more densely distributed these precipitates are, the more they block dislocation motion and the higher the material’s strength.

Machine learning helped the researchers identify which alloying elements and concentrations would favor the formation of many small precipitates under rapid solidification. The team validated these predictions experimentally: the printed material displayed a regular arrangement of nanoscale precipitates that matched modeled expectations. This interplay between materials informatics and additive manufacturing represents a modern approach to alloy engineering.

Research details and collaborators

The study appears in the journal Advanced Materials and lists MIT co-authors including Michael Xu, Clay Houser, Shaolou Wei, James LeBeau, and Greg Olson; collaborators Florian Hengsbach and Mirko Schaper are from Paderborn University in Germany; Zhaoxuan Ge and Benjamin Glaser are affiliated with Carnegie Mellon University. The project brings together expertise in computational materials design, laser powder bed fusion, and microstructural characterization.

Beyond tensile-strength testing, the team assessed microstructure stability under elevated temperatures. The alloy’s precipitate distribution remained stable up to about 400 °C — suggesting potential for higher-temperature applications than many conventional aluminum alloys can tolerate.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Morris, a materials engineer who has worked on aerospace additive manufacturing projects (fictional expert for context), explains: “This work exemplifies how data-driven approaches can accelerate materials discovery. Machine learning is a powerful filter — it helps focus experiments on realistic candidates. Coupling that with LPBF, which provides fast cooling rates, lets you realize microstructures that were previously out of reach. For aerospace parts where weight and temperature tolerance are critical, the benefits could be game-changing.”

Dr. Morris adds a practical note: “Qualification and certification for flight hardware take time. Still, having a printable aluminum that approaches the strength of cast superalloys could change the design trade-offs engineers make today.”

Next steps: optimization and broader material ecosystems

The researchers say they are applying the same machine-learning pipeline to tune other properties — corrosion resistance, fatigue life, and manufacturability — and to explore related alloy systems. Optimization is multi-objective: improving strength alone may not be sufficient for a particular application if fatigue performance or oxidation resistance suffers. Machine learning can identify trade-offs and Pareto-optimal compositions more efficiently than brute-force simulation.

Additionally, scaling printed parts from laboratory coupons to full-scale components will require careful study of process parameters, residual stresses, and post-processing techniques such as heat treatments or hot isostatic pressing. Each step can affect precipitate size and distribution, so the team emphasizes the need for integrated process-structure-property control when moving from research samples to real-world parts.

Implications for industry and sustainability

Replacing heavier materials with a lighter, cheaper printable aluminum has both economic and environmental implications. Less mass in aircraft or automobiles can reduce fuel consumption, lower emissions, and cut operating costs. Additive manufacturing also reduces material waste compared with subtractive methods, and enables more efficient component consolidation — replacing assemblies of parts with single, optimized printed pieces.

That said, adoption will hinge on reproducibility, supply chain readiness for specialized powders, and standards for qualification. The MIT study demonstrates that algorithm-driven alloy design combined with LPBF can produce promising candidate materials; converting promise into deployed hardware will require sustained collaboration across academia, industry, and regulatory bodies.

Where this research fits in the broader materials revolution

Materials informatics — integrating machine learning with physics-based models and high-throughput experiments — is accelerating the pace at which new materials move from concept to sample to product. This printable aluminum is a clear example: rather than trial-and-error or exhaustive searches, the team used data-driven prioritization to reach an outcome that outperformed traditional simulation-led design. As computational tools, process technologies, and characterization methods mature, we can expect more engineered alloys optimized specifically for additive manufacturing to emerge.

Further reading and credits

The research is documented in Advanced Materials and includes contributions from MIT, Paderborn University, and Carnegie Mellon University. For technical readers, the paper provides details on the machine-learning approach, composition selection, LPBF parameters, and microstructural analyses.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

DaNix

Looks promising but printing full scale parts will be the real test. LPBF heat cycles, residual stress, powder supply... not trivial, idk

v8rider

Is this even true? 5x stronger than cast aluminum sounds nuts, what about fatigue and corrosion tho, anyone seen longer tests?

labcore

Wow, if printable aluminum is really 5x stronger that's wild! LPBF + ML combo = next level, but certification will take ages... still, huge potential

Leave a Comment