8 Minutes

Using Georgia State University's CHARA Array, astronomers have for the first time captured high-resolution images of novae within days of their eruptions, revealing unexpected complexity in how these stellar explosions eject material, form shocks, and produce high-energy radiation.

Why these nova images change what we thought

Novae are eruptions on the surface of white dwarfs that occur when the compact star siphons hydrogen-rich material from a companion. When enough fuel accumulates, a runaway nuclear reaction ignites, blowing off surface layers in an explosive event visible across the galaxy. Until now, the earliest moments after ignition remained largely invisible; the expanding debris looked like a single unresolved point of light to most telescopes. Interferometry at the CHARA Array changed that.

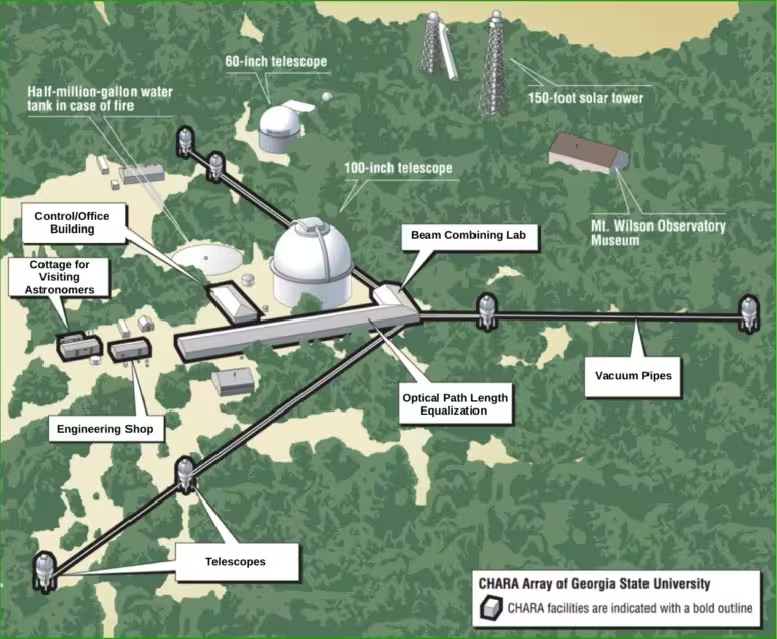

By coherently combining light from multiple telescopes spread across Mount Wilson Observatory, the CHARA team achieved angular resolution fine enough to spatially resolve the ejected material just days after outburst. Those images show that novae are not simple single-shell explosions. Instead, they can launch multiple, distinct flows of gas — sometimes in perpendicular directions — and in other cases delay the expulsion of their envelope for weeks. These behaviors directly affect how and when shock waves form, and thereby when novae emit high-energy photons like gamma rays.

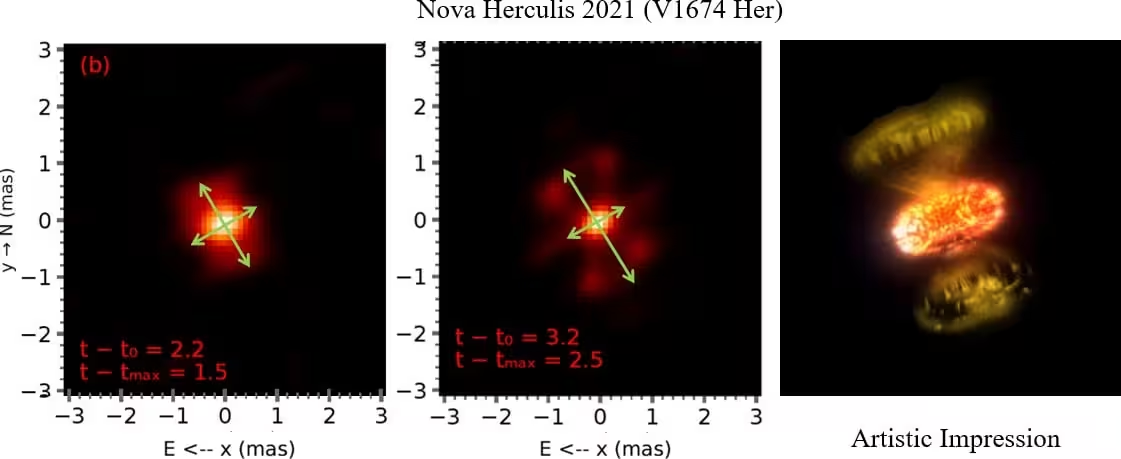

Scientists at Georgia State's CHARA Array captured images of Nova V1674 Herculis — one of the fastest stellar explosions on record. Images of Nova V1674 Herculis obtained 2.2 days (left) and 3.2 days (middle) after the explosion. The images reveal the formation of two distinct, perpendicular outflows of gas, as highlighted by the green arrows. The panel on the right shows an artistic impression of the explosion. Credit: The CHARA Array

Two novae, two different stories

The international study published in Nature Astronomy focused on two novae from 2021 that behaved in dramatically different ways. Nova V1674 Herculis produced one of the fastest recorded eruptions, brightening and fading within a few days. CHARA images taken 2.2 and 3.2 days after the explosion revealed two separate, perpendicular outflows of gas. Those orthogonal streams collided and generated shock fronts at roughly the same time NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected GeV gamma rays from the system. This direct spatial and temporal association provides compelling evidence that interacting outflows — not a single spherical shell — are the source of gamma-ray production in at least some novae.

By contrast, Nova V1405 Cassiopeiae evolved slowly. For more than 50 days after the initial energy release, its outer envelope remained intact, only to be expelled later in a sudden event. When that delayed ejection finally occurred, new shocks formed and Fermi again recorded gamma-rays. The delayed-release scenario demonstrates that some novae undergo multi-stage mass ejection, with important consequences for how shocks develop and how energy is converted into high-energy particles and photons.

How interferometry and spectroscopy revealed the dynamics

Interferometry allowed astronomers to map the shape and timing of the outflows with unprecedented angular detail. But images alone tell only part of the story. The team combined CHARA's interferometric snapshots with spectroscopic observations from major facilities including Gemini. Spectra provide velocity and composition information by showing Doppler-shifted emission and absorption lines, the 'fingerprints' of moving gas. When new spectral features appeared, they lined up with the spatial structures visible in the interferometric images, a one-to-one confirmation that the observed shapes correspond to distinct physical flows and collisions.

The CHARA Array is located at the Mount Wilson Observatory in the San Gabriel Mountains of southern California. The six telescopes of the CHARA Array are arranged along three arms. The light from each telescope is transported through vacuum pipes to the central beam combining lab. Credit: Georgia State University/The CHARA Array

Why timing matters

- Early imaging captures the geometry at the moment shocks form; missing those days obscures cause-and-effect.

- Comparing image snapshots to gamma-ray light curves shows whether high-energy emission coincides with outflow collisions.

- Delayed ejection changes the shock environment: when a slower envelope is expelled after a fast wind, the resulting collision can be especially efficient at accelerating particles.

Implications for shock physics and high-energy astronomy

These observations elevate novae from curious optical transients to laboratories for studying shock acceleration and particle physics in astrophysical plasmas. Over its first 15 years, Fermi-LAT detected GeV gamma rays from more than 20 novae, establishing that these modest stellar explosions can produce relativistic particles. The CHARA images provide the missing spatial context: they show how geometry and timing of mass ejection create the shock conditions necessary to accelerate particles to energies that emit gamma rays.

Understanding shock formation in novae helps bridge gaps between different astrophysical systems that produce shocks, from supernovae to colliding-wind binaries. Novae occur frequently and on human timescales, offering repeated opportunities to test shock physics under different initial conditions. The variety — multiple outflows, perpendicular flows, and delayed envelope release — shows that there is no single nova template. Instead, the morphology of the explosion depends on binary parameters, rotation, magnetic fields, and possibly the structure of the accreted layer.

This is an extraordinary leap forward,' said John Monnier, a co-author and interferometric imaging expert. 'The fact that we can now watch stars explode and immediately see the structure of the material being blasted into space is remarkable. It opens a new window into some of the most dramatic events in the universe.'

The circles mark the domes of the six CHARA Array telescopes at the historic Mount Wilson Observatory. Credit: Georgia State University/The CHARA Array

How these results were made possible

Success required rapid coordination: nova discoveries are unpredictable and evolve quickly, so CHARA operators needed flexibility to reconfigure nights and point the array at newly reported targets. Combining interferometry with rapid-response spectroscopy and continuous monitoring by space telescopes like Fermi made it possible to connect spatial structure with evolving emissions across the electromagnetic spectrum. This multi-messenger, multi-wavelength approach is now a model for studying other fast transients.

Beyond revealing physics, these methods refine how researchers plan future nova campaigns. Early alerts from all-sky surveys can trigger interferometric observations; spectrographs then follow the evolving velocities and composition. As more systems are observed with this combined approach, patterns may emerge that link explosion geometry to binary properties or to pre-explosion accretion history.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Hernández, an observational astrophysicist not involved with the study, commented: 'Seeing these outflows directly changes the questions we ask. We used to model novae as spherical shells because that was all our instruments could resolve. Now we must incorporate asymmetry, episodic ejection, and interaction between multiple flows. That complexity actually makes novae more powerful diagnostic tools for shock acceleration and plasma physics than we suspected.'

What's next for nova research

The study's authors emphasize that this is the beginning of a new era. More coordinated campaigns will expand the sample of novae observed with interferometry, enabling statistical studies of ejection patterns and shock efficiencies. Upgrades to arrays, larger baseline interferometers, and faster instrument response times will sharpen images earlier and over longer durations. Complementary facilities — radio arrays that trace synchrotron emission from relativistic electrons, X-ray telescopes that probe hot shocked gas, and gamma-ray observatories monitoring high-energy output — will together build a full picture of how novae convert nuclear energy into kinetic energy and high-energy radiation.

As Elias Aydi, lead author and Texas Tech University astronomer, put it: 'Instead of a single flash, we can now watch the choreography of a stellar explosion. Novae are turning out to be far richer and more fascinating than we imagined.'

These findings not only rewrite aspects of nova theory but also underline the value of rapid, high-resolution imaging for transient astronomy. With better spatial and temporal coverage, the next decade promises a more complete understanding of how modest stars can create powerful shocks and act as laboratories of extreme physics.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

DaNix

Interesting, but seems they caught 2 novae so far, small sample. hope more follow ups and faster triggers pls 🤞 still cool tho

mechbyte

Is the gamma-ray link solid tho? correlation is neat but causation still feels fuzzy, need more samples.

astroset

wow, actually seeing the flows form that fast is mindblowing. perpendicular outflows? wild. makes me wanna rewatch the vids, and read more rn.

Leave a Comment