5 Minutes

Researchers have found that rilmenidine, a medication commonly prescribed for hypertension, can extend lifespan and improve health markers in laboratory animals. The drug appears to act like a calorie-restriction mimetic at the cellular level — raising hopes that existing medicines might be repurposed to delay aspects of aging without extreme diets.

From worms to mice: surprising signs of longevity

In experiments with Caenorhabditis elegans, a microscopic nematode frequently used in aging research, both young and old worms treated with rilmenidine lived longer and showed improvements in multiple health indicators. Those effects resembled the benefits produced by caloric restriction — a well-known intervention that extends lifespan across many species but is difficult to sustain and can carry side effects like hair thinning, dizziness, and bone loss.

"For the first time, we have been able to show in animals that rilmenidine can increase lifespan," said molecular biogerontologist João Pedro Magalhães of the University of Birmingham. The study, published in Aging Cell, tracked gene activity and physiological changes that mirrored calorie-restricted states.

How rilmenidine may mimic calorie restriction

At the molecular level, rilmenidine seems to alter cellular energy signaling in ways that overlap with caloric restriction pathways. Researchers observed similar gene-expression changes in the kidney and liver tissues of mice given the drug, suggesting that the effect is not limited to worms and may operate across mammals.

One striking finding involved a receptor called nish-1. When researchers deleted the gene for nish-1, the lifespan-extending effects of rilmenidine disappeared. Restoring nish-1 brought those benefits back, pointing to this signaling hub as a potential target for future anti-aging therapies.

Why repurposing drugs matters for aging research

Developing new drugs from scratch is time-consuming and expensive; repurposing medicines already approved for other uses can accelerate the path to clinical testing. Rilmenidine is attractive for several practical reasons: it is orally administered, widely prescribed, and generally well tolerated. Reported side effects are relatively uncommon and typically mild — palpitations, insomnia, and drowsiness in a minority of patients.

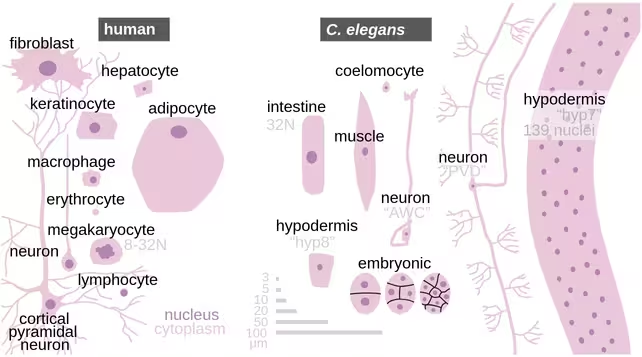

Still, translating results from nematodes and mice into human treatments is far from guaranteed. C. elegans shares many genetic pathways with humans, which is why it’s a staple for aging studies, but it remains a distant relative. The mouse data strengthen the case, yet large, controlled human studies are needed to evaluate safety and efficacy as an anti-aging intervention.

Lessons from related drugs

The rilmenidine story echoes growing interest in other repurposed drugs. For example, observational analyses of metformin — a widely used diabetes medication — have suggested improved long-term survival in older adults in some cohorts. A long-term US study of postmenopausal women found that those taking metformin had a lower risk of dying before age 90 compared with women taking a different diabetes medication, though cause-and-effect cannot be inferred from observational data alone.

Those findings underscore both the promise and the limits of repurposing: large observational datasets can point to candidates, but randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are necessary to prove benefit for aging or longevity.

What’s next for rilmenidine research?

Scientists are planning further preclinical studies to map the pathways by which rilmenidine acts, and to test dosage ranges and long-term effects in mammalian models. If results remain encouraging, the next step would be carefully designed human trials to assess whether the drug can safely extend healthspan — the years lived in good health — without unacceptable risks.

"With a global aging population, the benefits of delaying aging, even slightly, are immense," Magalhães noted. "Repurposing drugs capable of extending lifespan and healthspan has a huge untapped potential in translational geroscience."

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Ruiz, a geroscience researcher not involved with the study, commented: "These findings are promising because they target conserved metabolic pathways. But animal lifespan extension doesn’t always predict human outcomes. The focus now should be on mechanistic studies that inform safe, targeted clinical trials. If a drug like rilmenidine can safely reproduce calorie-restriction benefits, it could change preventive medicine for older adults."

For now, rilmenidine offers a tantalizing clue: existing medications may hold unexpected potential to modulate aging biology. The path from worm to clinic is long, but this research adds a valuable entry to the shortlist of candidate longevity therapies.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

atomwave

Wow imagine a pill that gives CR benefits! If safe in humans, lifechanging. Still, bet decades of trials ahead... fingers crossed

bioNix

Could rilmenidine really mimic CR in people? Skeptical but intrigued. Mouse+worm data promising, but humans? need rigorous RCTs, not hype.

Leave a Comment