6 Minutes

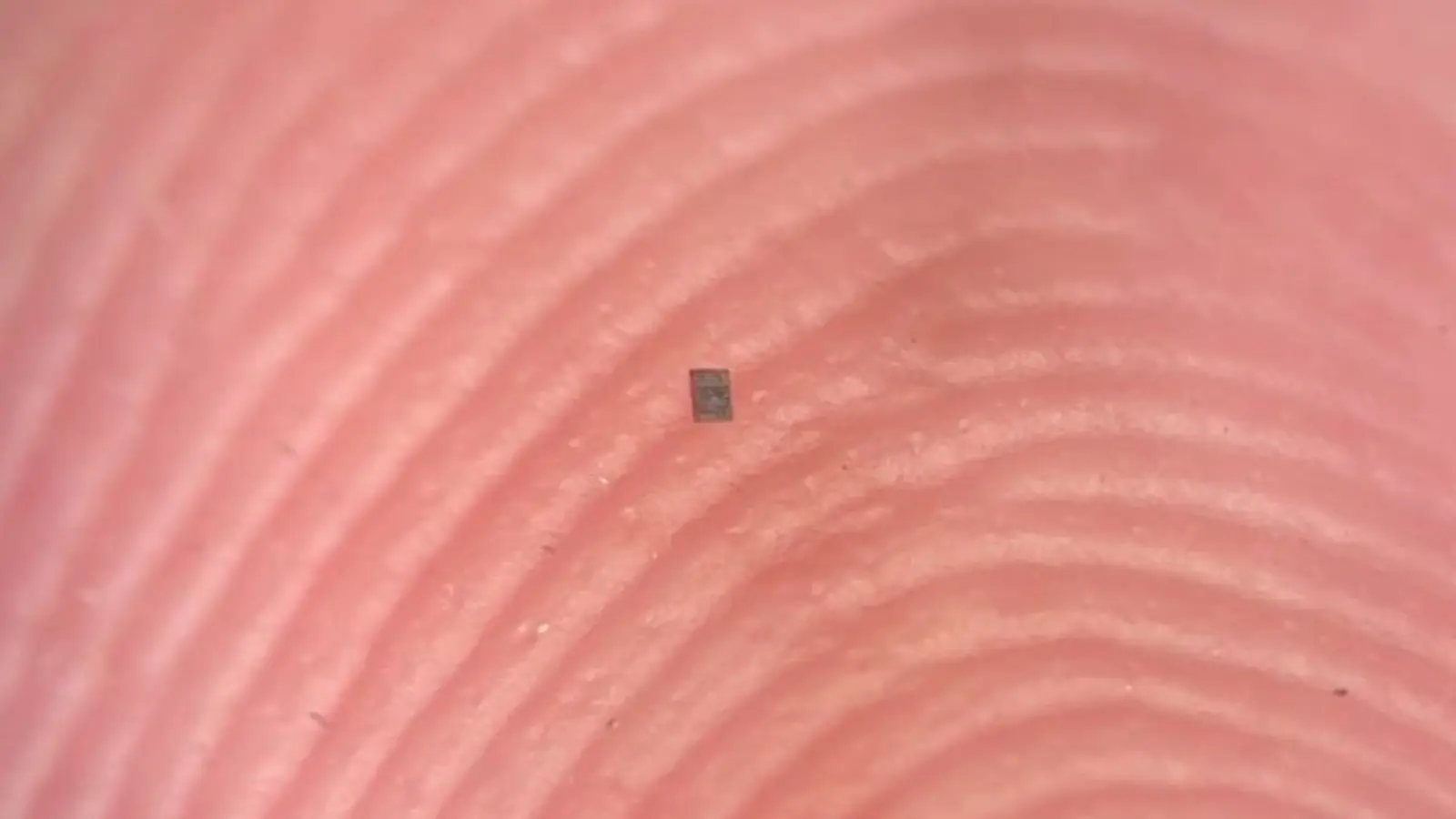

Engineers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan have built an almost invisible, fully programmable microrobot that can sense, compute and move on its own when submerged in fluid. No bigger than a grain of salt, this device—small enough to balance on the ridge of a fingerprint—represents a dramatic shrinkage of prior autonomous robotic platforms and opens new possibilities for microscale robotics.

How tiny is “tiny” and why that matters

The new microrobot measures roughly 200 by 300 micrometers across and just 50 micrometers thick. To give perspective: it is smaller than a freckle and can sit on a penny without obscuring the coin’s stamped date. Blink and you could lose it.

Size matters at the micrometer scale because the physical rules that govern motion change. Gravity and inertia — dominant at human scales — become negligible. Viscous forces and drag take over. As Marc Miskin, a nanorobotics engineer at the University of Pennsylvania, explains: when you're small enough, "pushing on water is like pushing through tar." Overcoming these fluidic challenges required rethinking propulsion, control and computation from the ground up.

What’s packed into a robot the size of a grain of salt

Despite its minuscule volume, the platform includes a processor, memory, sensors, receivers and a power source. The team fitted each microrobot with tiny solar cells that harvest roughly 100 nanowatts of power from LED illumination — enough to run basic sensing, decision-making and motion. The robot can take temperature readings of the fluid around it and communicate those measurements through patterned motion, a behavior compared to the waggle-like dances of honeybees.

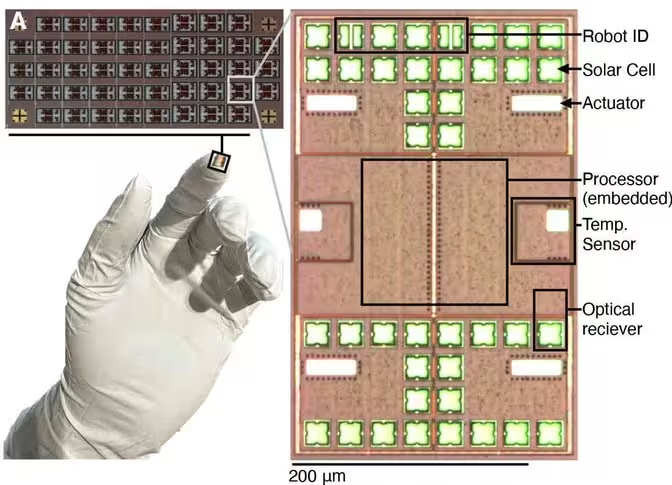

Microbots produced in a sheet (top left) roughly the area of a fingertip (bottom left). Each bot contains solar cells, optical receivers, two temperature sensors, a processor for taking in information and making decisions, four actuator panels that drive its motion, and four receivers that allow the robot to identify incoming programs.

Propulsion without moving limbs

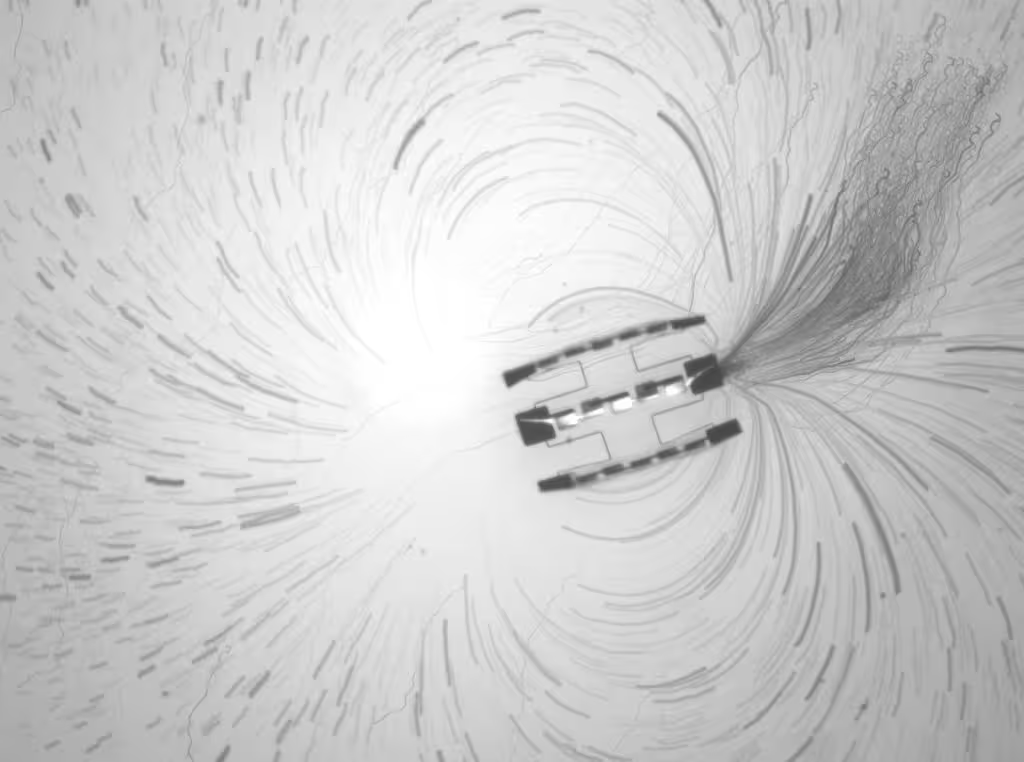

Traditional locomotion — tiny limbs or paddles — becomes fragile and impractical at this scale. Instead, the Penn team created a propulsion method with no exposed moving parts. The microrobot generates an electric field around its body that drives molecular flows in the surrounding fluid. The device effectively changes the local flow field: it’s as if the robot both swims in a river and pushes the river to move.

A projected time-lapse of tracer particle trajectories near a robot consisting of three motors tied together. (Lucas Hanson & William Reinhardt/University of Pennsylvania)

Miniature computing: a rethink of processors and code

Getting a functioning computer into such a tiny package required a complete rethink of how to design circuits and programs. Researchers at the University of Michigan developed a microscopic computer architecture that uses minimal power and memory, tailored to the constraints of microrobotic hardware. David Blaauw, a computer scientist involved in the project, notes the team redesigned both hardware and software to fit the unique energy and size limitations.

Because onboard memory is currently limited, the microrobot runs simple, locally executed programs. But these basic behaviors are enough for autonomous sensing, decision-making and locomotion. The platform also includes optical receivers that allow robots to accept new programs from light signals, enabling remote reprogramming or coordination.

Collective behavior and endurance

Individually, each device is rudimentary. Together, they can synchronize and form coordinated groups that behave like schools of fish. The researchers demonstrated that swarms of these microrobots can operate autonomously for months if periodically recharged by LED illumination. The implications are broad: collective, long-lived microrobots could perform environmental sensing, swarm inspection tasks, or, eventually, biomedical monitoring inside fluids.

Scientific context and potential applications

Previous autonomous, programmable microrobots were on the order of a millimeter — already a technical feat achieved more than two decades ago. Shrinking functionality by roughly 10,000-fold required innovations that cross optics, microelectronics, fluid mechanics and materials science.

- Biomedical monitoring: With further miniaturization and biocompatible packaging, microrobots might one day patrol tissues or fluids to detect infection or inflammation.

- Environmental sensing: Swarms could map chemical or thermal gradients in microenvironments such as soil pores or microfluidic systems.

- Microassembly and inspection: Small, programmable devices could inspect or manipulate microfabricated structures inaccessible to conventional tools.

Expert Insight

"This is really just the first chapter," says Marc Miskin. "We've shown that you can put a brain, a sensor, and a motor into something almost too small to see, and have it survive and work for months."

Adding perspective, a fictional but realistic expert comment helps frame broader impact:

Dr. Elena Ruiz, microsystems engineer

"What makes this work exciting is the systems-level approach. Solving propulsion, power and computation together — rather than one at a time — unlocks capabilities we didn't think feasible at this scale. Over the next decade, iterative improvements in memory, energy harvesting and materials could move these devices from lab curiosities to useful tools in medicine and environmental science."

The study detailing the microrobot was published in Science Robotics, and the team is already exploring ways to expand onboard memory and add richer behaviors. From tiny hardware breakthroughs come large-scale possibilities: networks of autonomous microrobots that sense, compute and act inside fluid environments may reshape fields from diagnostics to environmental monitoring.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Reza

Is this even true? Long-lived swarms inside tissues sounds cool but kinda scary, what about biocompatibility, immune response, or removal if they pile up?

atomwave

Wow these things are insane, blink and they're gone. Tiny robots sensing and 'swimming' in fluids... kinda spooky but also thrilling, if thats real

Leave a Comment