5 Minutes

New research from Korea adds a surprising twist to the gut–brain conversation: bacteria that normally live in the mouth can colonize the gut, produce metabolites that reach the brain, and potentially accelerate Parkinson’s disease. The study maps a biochemical route from oral microbes to neuronal damage and points to new targets for prevention and therapy.

A new study suggests that microbes originating outside the brain may influence the earliest stages of neurodegenerative disease. By uncovering a biological pathway linking microbial activity to neuronal damage, the research challenges traditional views of how Parkinson’s disease develops.

From mouth to gut: how a cavity bug ends up in the brain

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder defined by tremor, rigidity, slowed movement and, at its core, the loss of dopamine-producing neurons. Epidemiological studies have long hinted at differences in the gut microbiome of people with Parkinson’s versus healthy controls, but pinpointing causative microbes and mechanisms has been difficult.

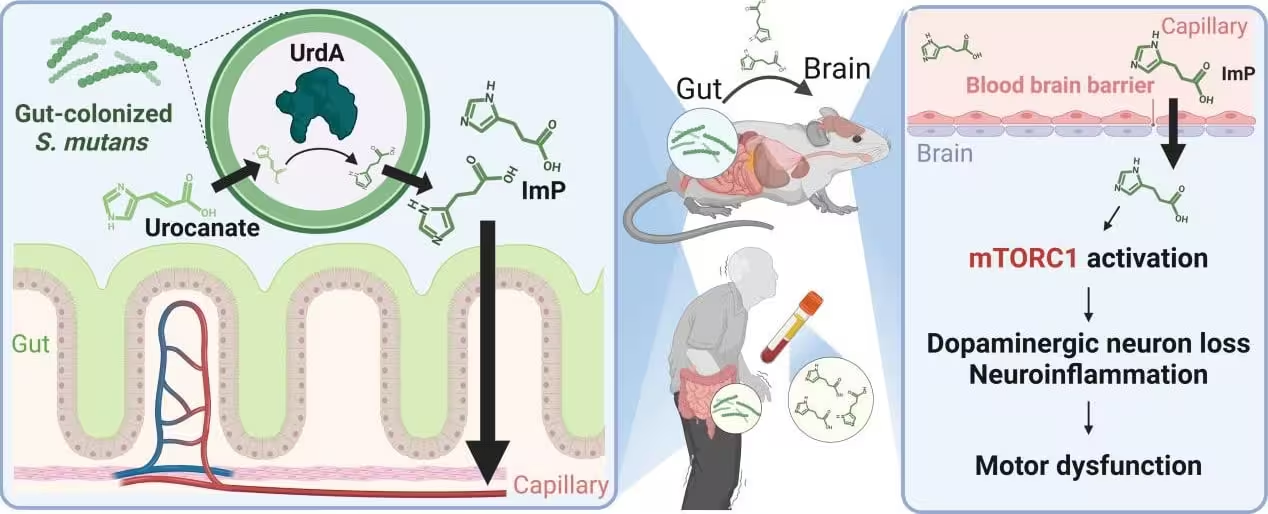

The new study identifies Streptococcus mutans — a bacterium most people associate with tooth decay — as one of the culprits. Researchers found elevated levels of S. mutans in the intestines of Parkinson’s patients. Once established in the gut, the bacterium produces an enzyme named urocanate reductase (UrdA) and a metabolic byproduct called imidazole propionate (ImP).

A metabolite that crosses borders: ImP and the brain

Imidazole propionate is central to the study’s narrative. Scientists detected higher ImP concentrations both in the gut and in the bloodstream of people with Parkinson’s, suggesting systemic circulation. Using mouse models, the team showed that introducing S. mutans into the gut or engineering E. coli to express UrdA raised ImP levels in blood and brain tissue.

These biochemical changes were accompanied by hallmarks of Parkinson’s pathology: loss of dopaminergic neurons, increased neuroinflammation, impaired motor function and greater aggregation of alpha-synuclein — the protein that forms the characteristic clumps seen in Parkinson’s brains.

How does ImP harm neurons?

Laboratory data point to activation of the mTORC1 signaling complex as a key step. When mTORC1 becomes overactive, cellular processes that maintain neuronal health can go awry, promoting inflammation and protein aggregation. Importantly, pharmacologically inhibiting mTORC1 in mice reduced neuroinflammation, neuronal loss and motor deficits, linking the microbial metabolite to a targetable pathway.

Diagram of Metabolite Accumulation in the Brain and Parkinson’s disease Induction Following Oral Bacteria Colonization in the Gut.

What the team did and who led the research

The study is a collaborative effort led by Professor Ara Koh and doctoral candidate Hyunji Park at POSTECH’s Department of Life Sciences, with collaborators at Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine and Seoul National University College of Medicine. Their experiments combined human microbiome analysis, metabolite measurements and controlled mouse models to connect oral microbes to brain pathology. The full findings were published in Nature Communications.

“Our study provides a mechanistic understanding of how oral microbes in the gut can influence the brain and contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease,” said Professor Ara Koh. “It highlights the potential of targeting the gut microbiota as a therapeutic strategy, offering a new direction for Parkinson’s treatment.”

Implications for prevention and future therapy

The implications are twofold. First, basic oral hygiene and dental health could be more important than previously appreciated for long-term neurological health — a subtle but actionable public-health point. Second, the identification of ImP and the UrdA enzyme opens avenues for therapeutic intervention: blocking microbial colonization, inhibiting UrdA activity, neutralizing ImP, or modulating mTORC1 signaling could all be explored as strategies to slow or prevent neurodegeneration.

The study also underscores the complexity of the gut–brain axis: microbes that originate in one body site (the mouth) may seed another (the intestine) and produce metabolites that travel systemically to affect distant organs, including the brain.

Expert Insight

Dr. Lena Rothman, a neuroimmunologist at a major medical center (commenting independently), said: “This paper elegantly connects colonization, metabolite production and a defined signaling pathway. While mouse models are not a perfect stand-in for human disease, identifying ImP and the mTORC1 link gives researchers concrete targets — both for biomarkers and for therapies.”

Future research will need to determine how common S. mutans colonization of the gut is across populations, whether ImP levels predict disease risk or progression, and which interventions are safe and effective in humans. Meanwhile, the study adds urgency to integrating oral health, microbiome science and neurology in research and clinical practice.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

Reza

Wow my dentist nagging about flossing just got real. kinda scary but also empowering. brush more, floss, checkups lol

atomwave

Hold up, S. mutans from mouth to brain? sounds like sci fi, wild if true. But where's the human proof, more cohorts pls

Leave a Comment