6 Minutes

This year the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) took a decisive step: it formally restored recognition of a distinct form of diabetes long tied to severe undernutrition. Often overlooked in global health debates, this malnutrition-associated diabetes—now being called type 5—is estimated to affect millions in low- and middle-income countries and demands different diagnostic and treatment approaches than classic type 1 or type 2 disease.

Why a new diabetes label matters

For decades clinicians and researchers argued over whether a malnutrition-related diabetes existed as a separate entity. First described in the 1950s in Jamaica, the condition was acknowledged by the World Health Organization in the 1980s, then dropped again in 1999 amid concerns about inconsistent evidence. Now the IDF is urging other health authorities to accept a fifth category—type 5 diabetes—so researchers, funders and clinicians can finally agree on how to identify and treat it.

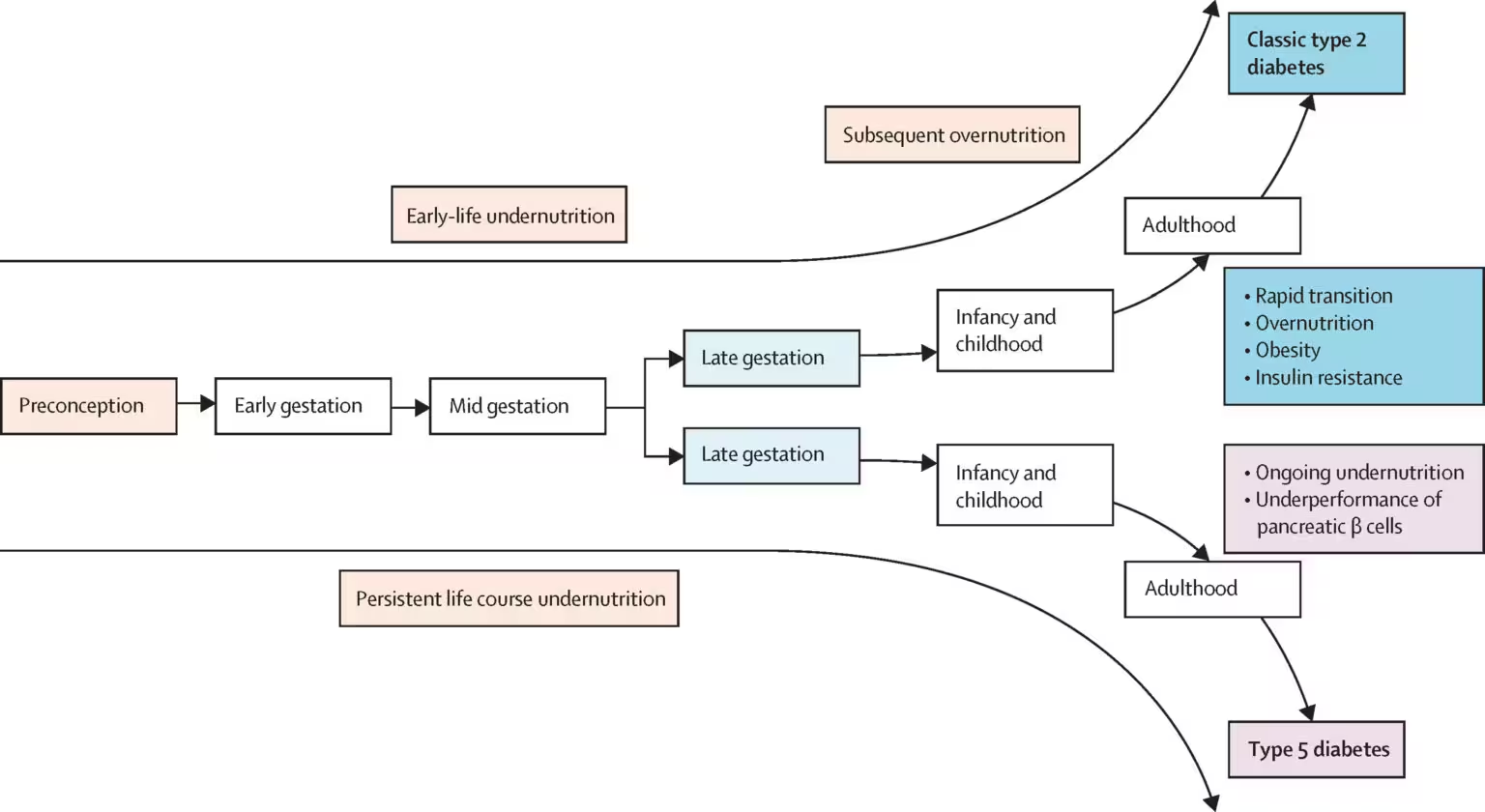

What sets type 5 diabetes apart is its origin: instead of being driven primarily by obesity, pregnancy, autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing cells, or pancreatic injury, it appears linked to chronic nutrient deficits during critical stages of growth. That history of undernutrition is thought to impair pancreatic development and long-term insulin production, producing a metabolic picture unlike common type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Evidence from clinics and field studies

Recent studies—both in animals and human cohorts—have strengthened the case that early-life nutrient shortages can permanently alter pancreatic structure and function. Clinical work led by groups active in South Asia and Africa has documented patients who are insulin-deficient to a degree distinct from autoimmune type 1 disease, yet who maintain insulin sensitivity unlike people with classic type 2 diabetes.

The pattern matters clinically: if insulin production is low but target tissues still respond to insulin, standard type 2 therapies that aim to reduce insulin resistance may be irrelevant. Worse, excessive or poorly timed insulin replacement in settings of food insecurity can cause dangerous hypoglycaemia.

The small trials and observational studies published so far suggest millions of people could be affected—some estimates propose up to 25 million globally—concentrated in regions where prolonged food scarcity, poverty and limited healthcare access intersect.

Diagnosing and treating type 5: a practical challenge

One of the core problems has been diagnostic ambiguity. Without agreed criteria, clinicians often label these patients as type 1 or type 2 and manage them accordingly—sometimes with harmful results. Insulin dosing protocols developed for autoimmune diabetes, for example, may be inappropriate for someone whose insulin deficiency is partial and who is at continuous risk of undernutrition.

Leading experts argue that diagnostic guidelines must combine clinical history (notably early-life undernutrition), metabolic testing that shows a distinctive insulin and glucose profile, and, where possible, biomarkers that reflect pancreatic capacity. The IDF has launched a working group chaired by endocrinologist Meredith Hawkins to draft such criteria, set up a global registry and produce training materials for frontline health workers.

What treatment could look like

Therapeutic strategies for type 5 diabetes will likely differ from those used routinely in high-income settings. Some patients may require low-dose, intermittent insulin supplementation to prevent hyperglycaemia while minimizing hypoglycaemia risk. Others might benefit from oral agents or nutritional interventions that stimulate residual insulin secretion, alongside programs that address the underlying food insecurity.

Any approach must be pragmatic: glucose monitoring devices and continuous insulin delivery are often unaffordable in the regions hardest hit. That reality elevates the need for simple, safe algorithms that community health workers can use, plus investment in food security and maternal-child nutrition programs as a form of primary prevention.

Global health and research implications

Recognition by the IDF is more than a labeling exercise—it's a call to action. Without a formal category, the condition remains invisible to major funders and under-reported in global disease estimates. That in turn stymies research into unique pathophysiology, diagnostics and treatments tailored for resource-limited settings.

Some researchers hail the move as long overdue; others caution the data remain heterogeneous and diagnostic certainty will be hard to achieve quickly. Both perspectives agree on one point: the absence of consensus perpetuates misdiagnoses and missed opportunities for better care.

Where the disease is most common—parts of Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and increasingly in areas across Latin America and the Caribbean—interventions will require coordinated clinical guidance, community nutrition support, and investments in basic laboratory capacity.

Expert Insight

"When a patient’s pancreas has been shaped by years of poor nutrition, the metabolic signature doesn’t match classical textbooks," says Dr. Elena Morales, a global endocrinologist who has worked in field clinics in Kenya and India. "Clinical teams need tools that reflect that reality—simple diagnostic checklists, clear insulin-sparing protocols, and robust nutrition programs. Otherwise we risk doing harm with well-intentioned treatments."

What to watch next

The IDF working group aims to publish diagnostic criteria and treatment recommendations and to create a multinational registry to collect standardized data. That registry could illuminate prevalence trends and clarify whether the number of people with type 5 diabetes is rising or falling as regions experience changing nutrition patterns.

Progress depends on collaboration: endocrinologists, primary-care clinicians, public-health experts and community organizations must work together to translate a formal label into safer, more effective care—particularly where limited resources and food insecurity increase the stakes.

Policy and public-health priorities

Beyond clinical practice, responding to type 5 diabetes requires bolstering maternal and child nutrition, expanding access to affordable diagnostics, and integrating diabetes care into broader efforts to reduce poverty and hunger. That combination addresses both the root cause and the medical consequences.

The IDF's official recognition restores a long-sidelined diagnosis to the global health agenda. Naming the condition is the first step; the harder work will be building evidence-based tools and equitable health systems so that people whose diabetes stems from undernutrition finally receive the right care.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

skyspin

Is this even real? 25 million sounds huge, data seems patchy — where's the standard criteria? quick worry about misdiagnoses 😬

bioNix

Whoa, didn't expect a 'type 5', heartbreaking. Early nutrition shaping pancreas, wow. We need real policy change, not just labels

Leave a Comment