11 Minutes

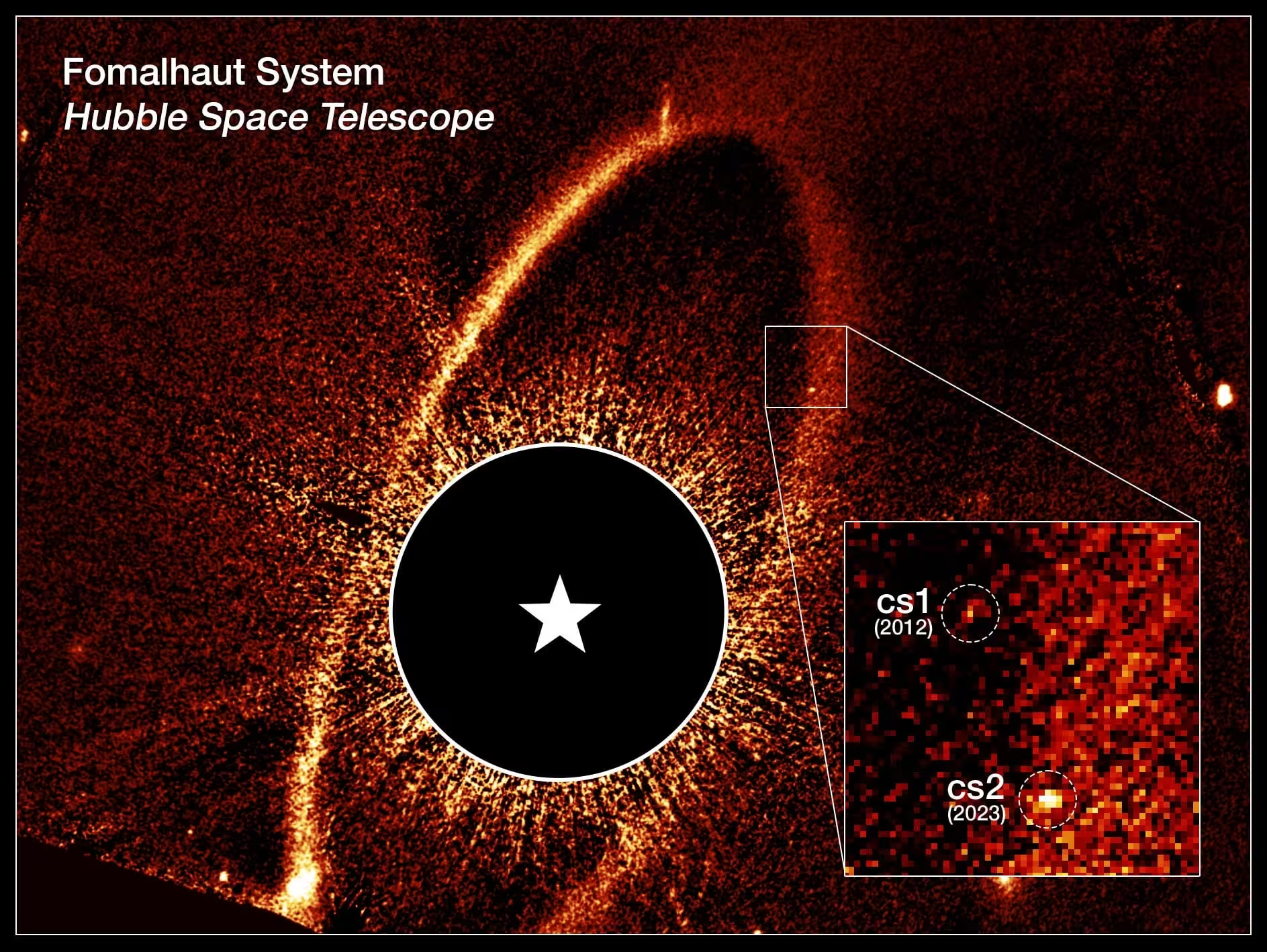

Astronomers have captured direct images showing the chaotic aftermath of two massive collisions in the young planetary system around the nearby star Fomalhaut. These rare snapshots reveal dust clouds produced when large rocky bodies—planetesimals—crashed into each other, offering a live view of the violent processes that shape nascent planetary systems.

A rare snapshot of planetary chaos

In the early stages of planetary systems, collisions among comets, asteroids and planetesimals are expected. Over millions of years these destructive encounters grind dust and ice into the debris that builds planets and moons. Yet direct images of collisions between large bodies have been elusive—until observations of Fomalhaut that began in the 2000s.

Fomalhaut sits only about 25 light years from Earth and is relatively young, roughly 440 million years old. That age places it in a dynamic phase of planetary assembly: big objects still collide frequently and volatile-rich material circulates within a broad debris disk. Using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (HST), astronomers first discovered a bright, point-like source in the star’s outer debris belt in 2004. At the time it was cataloged as a candidate planet and called Fomalhaut b.

Follow-up monitoring revealed a surprise. The bright source did not behave like a stable planet; its brightness and motion changed with time. In 2012 and later images, astronomers recognized that the apparent point source could instead be a dense dust cloud formed by a massive impact. By 2014, that original source had faded away. Then, in 2023, HST captured a second, separate bright dust cloud—now labeled cs2—near the belt. Together these observations mark the first direct imaging of collisions between large bodies in any planetary system beyond our own.

How big were the colliding bodies?

Brightness and modeling of the dust clouds indicate the colliding planetesimals were large: at least about 60 kilometers (37 miles) across. That is roughly four times the diameter of the asteroid believed to have struck Earth 66 million years ago. Objects of this size are intermediate between typical solar system asteroids and dwarf planets—large enough to generate enormous, observable debris clouds when they smash together.

Paul Kalas, adjunct professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley and lead author of the recent study, described the detection as watching the aftermath of two planetesimals collide and produce a dust cloud that scatters starlight. Over tens of thousands of years, he said, the disk around Fomalhaut could be sparkling with similar collisions—like holiday lights flickering across the system.

Mark Wyatt, a theorist at the University of Cambridge and a coauthor on the work, noted that the observation provides constraints on both the sizes of colliding bodies and the population of such objects in the disk. From the brightness and frequency of these dust clouds, Kalas and colleagues estimate there may be on the order of 300 million planetesimals of comparable size orbiting Fomalhaut.

Debris rings, radiation pressure, and disappearing 'planets'

Fomalhaut is embedded in a wide debris belt about 133 astronomical units (AU) from the star—more than three times the distance of our Kuiper Belt from the Sun. The belt’s sharp inner edge hinted early on that planets might be sculpting the structure. But bright point sources within or near a belt do not always mark planets.

Small dust particles are significantly affected by the host star’s radiation pressure; instead of following Keplerian orbits like a massive planet, a dust cloud can be pushed outward and can exhibit non-planet-like motion. The first circumstellar source, cs1 (formerly Fomalhaut b), initially mimicked planetary motion, but by 2013 it showed curved, outward-directed movement consistent with radiation-driven dispersal of small dust. The appearance of cs2 in 2023 strengthens the interpretation that these transient bright spots are impact-produced dust clouds rather than bona fide planets.

Previous observations also detected carbon monoxide gas in the Fomalhaut system. CO is a volatile molecule that suggests many of the planetesimals are volatile-rich, akin to the icy comets in our solar system. That volatile inventory affects how collisions evolve—icy bodies can liberate gas and produce different dust dynamics than dry rock impacts.

Implications for planet formation and collision frequency

Standard models of planetary formation predict that collisions between very large objects should be rare: perhaps one such catastrophic event every ~100,000 years in a forming system. Finding two such bright-impact signatures separated by less than two decades in a single system forces astronomers to reconsider either the statistical odds or aspects of those models.

There are two broad possibilities. One is pure chance: Fomalhaut happened to have two detectable collisions within the limited window of HST monitoring. The other is more intriguing—massive collisions may be more common during certain stages of disk evolution than models currently predict. If large impacts occur more frequently, they could play a larger role in shaping planetary architectures and volatile delivery than previously appreciated.

Moreover, these events provide a rare laboratory to probe internal structure and composition. The amount and scattering properties of dust, combined with gas detections, allow researchers to infer whether colliding bodies were porous, icy, or rock-dominated. That in turn feeds back into models of how planetesimals grow, fragment, and reassemble into planets.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Moreno, an observational astrophysicist specializing in circumstellar disks, commented: 'Directly imaging impact-generated dust clouds gives us a unique diagnostic of planet formation in action. The size, brightness, and motion of these clouds let us test how energy is partitioned during collisions and how quickly debris disperses. With Hubble and JWST working together, we can trace the evolution of a single event from days to decades and compare it to laboratory and simulation results.'

How these observations were made and why they matter for future missions

The discoveries relied primarily on the Hubble Space Telescope’s long-term imaging program targeting Fomalhaut beginning in the 1990s and continuing through intermittent observations in 2004, 2006, 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014. After a nine-year gap, Hubble imaging in 2023 revealed cs2. A lower-quality 2024 image and subsequent checks confirmed the dust-cloud interpretation. Additional observations in August 2025 showed cs2 remained visible and—importantly—about 30% brighter than cs1 had been when detected.

To follow the cloud’s expansion and determine its orbit precisely, Kalas and his team have been awarded observing time over the next three years with both HST and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) using NIRCam. JWST’s near-infrared sensitivity can help map the dust grain properties and any thermal emission, while repeated HST imaging provides high-contrast optical views of scattered light. Tracking how the cloud expands, fades, and moves will constrain particle sizes and the kinematics of the ejecta.

There are practical lessons for upcoming exoplanet imaging missions. Future observatories aiming to directly image Earth-like planets—such as the proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory—will rely on detecting faint point sources very close to bright stars. Kalas warns that dust clouds from collisions can masquerade as planets, producing transient point-like signals. Without time-series imaging and multi-wavelength characterization, a dust cloud could be mistakenly identified as a candidate exoplanet.

As Kalas put it, 'Once we start probing stars with sensitive future telescopes... we have to be cautious because these faint points of light orbiting a star may not be planets.' The Fomalhaut case is a timely reminder to pair direct imaging campaigns with temporal monitoring and spectro-photometric checks to distinguish real planets from ephemeral debris.

Next steps and future prospects

Follow-up observations will focus on several measurable goals: determine whether the cs2 dust cloud is expanding (and at what rate), map its orbital path, measure the particle size distribution, and detect any thermal emission or gas signatures with JWST. Those data will help infer the impact energy and the likely makeup of the colliding bodies.

Beyond Fomalhaut, these results motivate systematic monitoring of nearby young stars with bright debris disks. Many systems likely experience ongoing collisional evolution; catching additional events will refine statistical estimates of collision frequency and will test whether Fomalhaut is exceptional or representative.

Finally, the Fomalhaut observations bridge scales from small Solar System tests to extrasolar planet formation. The 2022 DART mission, which produced a modest dust cloud when it hit the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos, provides a calibration point; the Fomalhaut clouds are roughly a billion times larger in scale, but both events underscore shared physical processes across very different regimes.

We are, in essence, watching planetary systems assemble and reassemble in real time: catastrophic collisions, transient dust shrouds, and the slow sculpting of disks into stable planetary architectures. With Hubble, JWST and future observatories poised to monitor these fireworks, astronomers will have an increasingly clear window into the messy birth of worlds.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

DaNix

Cool capture, but feels a bit overhyped. HST luck + long monitoring = coincidence maybe. still nice data, want JWST spectra asap 🙂

Armin

Wait seriously? Two huge collisions in 20 years around one star, or are we just lucky observers? feels like the odds are off... curious how solid their stats are

mechbyte

Woah, seeing planets get born... or wrecked, is wild! Like cosmic fireworks, messy and beautiful. If only we could zoom in more, damn imagine the dust clouds up close.

Leave a Comment