4 Minutes

Astronomers have, for the first time, determined both the mass and distance of a planet that drifts freely through the galaxy without a host star. The discovery relies on a rare alignment and coordinated observations from telescopes on Earth and in space — a modern example of celestial sleuthing that opens a new window onto how planets form and get ejected.

How a dark, lonely planet revealed itself

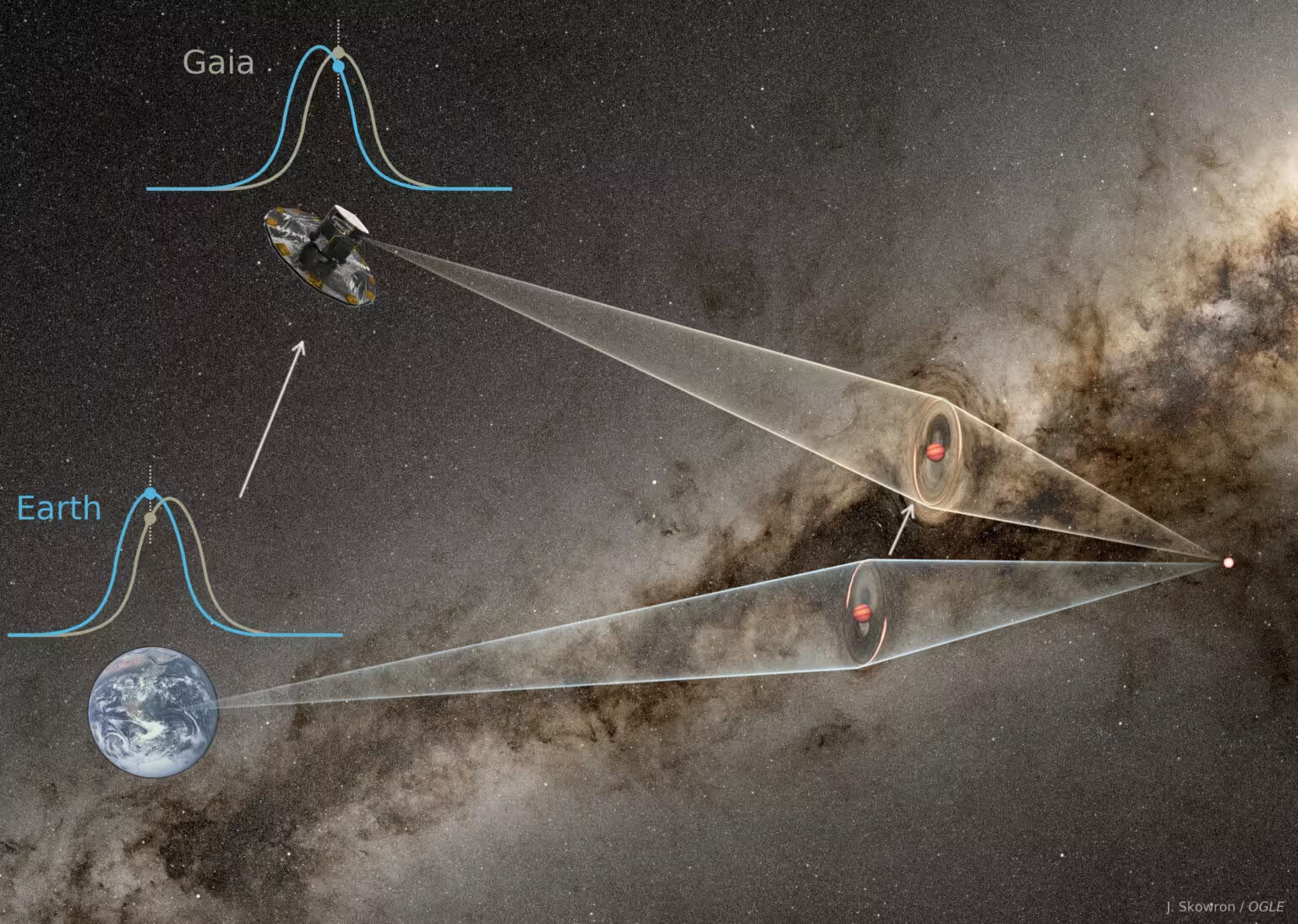

Rogue planets are extremely faint and nearly impossible to detect directly. Instead, astronomers find them through gravitational microlensing: when a foreground object (like a planet) passes in front of a distant star, its gravity briefly bends and magnifies the star's light. That fleeting brightening is the clue, but turning that signal into a mass requires knowing how far away the lensing object is — a major challenge when the lens is an unlit wanderer.

On 3 May 2024, several ground-based observatories in Chile, South Africa and Australia independently recorded such a microlensing event. Crucially, the retired Gaia spacecraft also observed the same event six times over 16 hours while it was roughly 1.5 million kilometers from Earth. That slight difference in viewpoint produced measurable timing and brightness offsets between the ground and space observations, effectively giving astronomers a stereoscopic measurement of the lens.

Weighing a planet with parallax: the method behind the headline

By comparing the light curves — the pattern of brightening and fading — recorded from the two vantage points, researchers estimated the distance to the lensing object and, with that distance, calculated its mass. The result: a solitary planet about 22 percent the mass of Jupiter, located roughly 9,785 light-years away toward the Milky Way’s center.

A diagram illustrating how the gravitational lensing event caused an apparent change in brightness, which was observed from Earth-based telescopes and Gaia in space, allowing its distance and mass to be calculated. (J. Skowron/OGLE)

Why this measurement matters

That mass — about a fifth of Jupiter’s — suggests the object likely formed inside a planetary system and was later ejected by gravitational interactions, the cosmic equivalent of billiards. Confirming both mass and distance for a rogue planet gives astronomers a rare data point to test models of planet formation, migration and ejection.

As astrophysicist Gavin Coleman of Queen Mary University of London has noted, coordinated observations like these show how space- and ground-based assets can overcome the usual ambiguity in microlensing events and provide direct constraints on rogue planet properties. The finding was published in the journal Science.

What’s next: wider searches and faster surveys

Looking ahead, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope — scheduled for launch in 2027 — will transform microlensing surveys. Its wide-field instruments will scan large areas of the sky far faster than Hubble, dramatically increasing the odds of catching similar lensing events. With Roman, astronomers expect to detect many more isolated planets and pin down their masses and distributions, clarifying how common ejection events are and how planetary systems evolve over time.

For now, this measurement stands as proof of concept: when timing, geometry and coordination line up, even a dark planet with no host star can be weighed from across the galaxy. It’s a reminder that careful observation — and a bit of cosmic luck — can illuminate the most elusive corners of the Milky Way.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment