5 Minutes

New research suggests that an imbalance in gut bacteria can reshape brain wiring and produce depression-like behavior associated with bipolar disorder — at least in mice. By transplanting fecal microbiota from people in a depressive phase of bipolar illness into rodents, scientists were able to reproduce both behavioral and neural features linked to the disorder.

How the mouse experiment worked — and why it matters

Researchers at Zhejiang University transferred fecal samples from volunteers diagnosed with bipolar disorder (during a depressive episode) into lab mice. The team combined behavioral testing, brain imaging, and genetic sequencing to track what changed after the transplant. Compared with mice that received bacteria from healthy donors, the recipients of bipolar-derived microbiota moved less, showed reduced interest in treats, and displayed other classic signs used in animal models of depression.

Why is that important? Animal models let scientists isolate one variable at a time. In this case, the gut microbiota was the manipulated factor. When behavior shifted only in mice given bipolar-sourced gut bacteria, the link between microbial communities and mood-related brain function became much stronger.

What brain scans and cell-level tests revealed

Brains of affected mice showed specific changes in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), a region central to decision-making and emotional regulation. The study reported fewer synaptic connections — the physical links between neurons — and weakened connectivity between the mPFC and reward-processing circuits. In short, the brain’s reward center appeared functionally disconnected, which matches core features of depressive behavior such as anhedonia (reduced ability to feel pleasure).

Genetic sequencing of the transplanted microbiome pointed to higher levels of bacterial genera already associated with poor health outcomes, including Klebsiella and Alistipes. Both have been flagged in earlier studies for potential mood-related effects, although the authors stress that more work is needed to pin down cause-and-effect at the species level.

Why lithium, not fluoxetine, produced improvement

To probe whether the induced depression resembled bipolar depression specifically, the researchers tested two medications: fluoxetine (an SSRI commonly used for major depressive disorder) and lithium (a first-line mood stabilizer for bipolar disorder). Fluoxetine did not restore normal behavior, but lithium produced a substantial behavioral rescue.

That pattern mirrors clinical experience: depressive episodes in bipolar disorder often respond differently to antidepressants than unipolar depression does. Lithium's known effects on dopamine signaling and neuron firing may help re-engage reward pathways that the altered microbiome had disrupted.

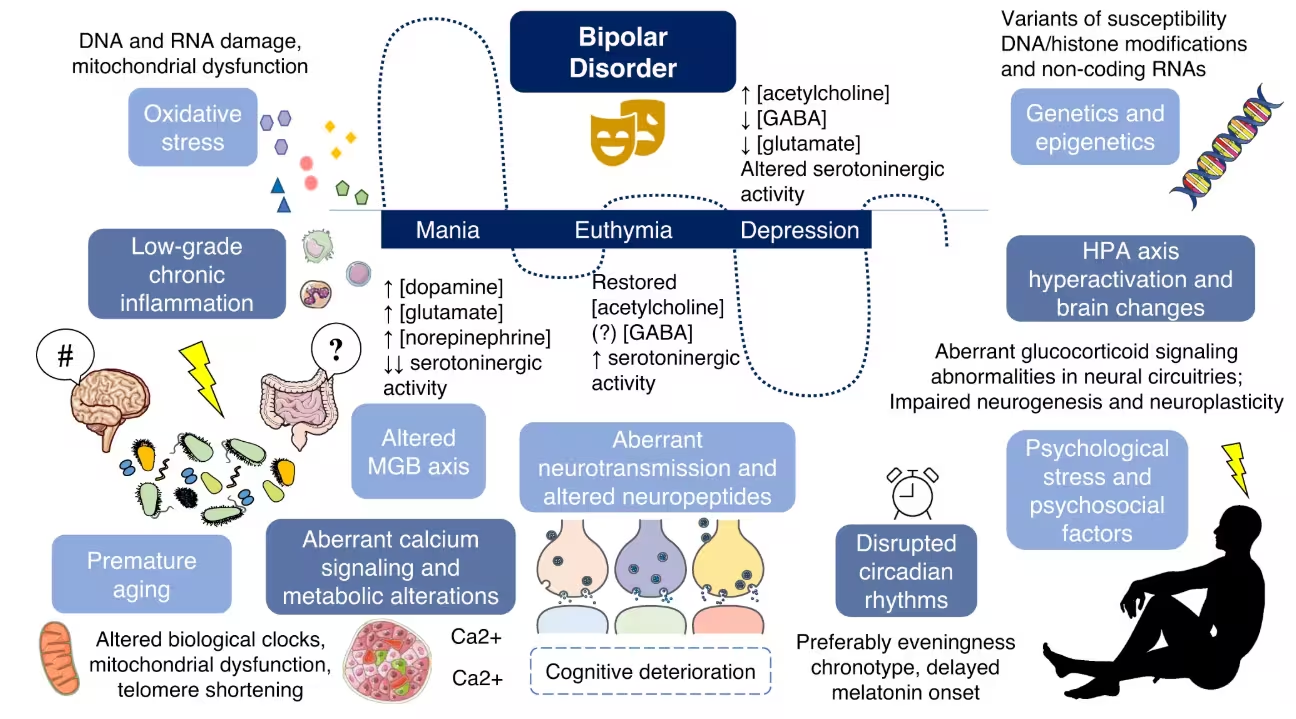

Bigger picture: gut microbes as one piece of a complex puzzle

The authors and independent experts caution that gut bacteria are unlikely to be the sole cause of bipolar disorder. The condition arises from a mix of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors — and the microbiota–gut–brain (MGB) axis is one contributing layer. Still, these findings support a model in which microbial imbalance can increase vulnerability to mood dysregulation, or exacerbate symptoms, by changing neural connectivity.

If replicated and extended to humans, this work opens new therapeutic possibilities: targeted microbiome interventions, including precision probiotics or microbiota restoration, might one day complement pharmacological and psychotherapeutic approaches. For now, the study shows how shifting gut communities can have direct, measurable impacts on brain circuits implicated in bipolar depression.

Implications for diagnosis and future research

Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder is common, in part because depressive episodes can look like major depression. Identifying biological signatures — whether microbial, molecular, or circuit-level — that distinguish bipolar depression from other forms could improve early diagnosis and guide treatment. The research, published in Molecular Psychiatry, calls for further investigation into which specific bacteria drive neural changes and whether similar patterns occur in people.

Expert Insight

“This study strengthens the idea that the gut and brain communicate in ways that matter for psychiatric conditions,” says Dr. Emily Hart, a clinical neuroscientist (fictional) who studies mood disorders and the microbiome. “The lithium responsiveness is particularly telling: it suggests the bacterial signal interacts with neural systems that are already known to be central to bipolar disorder. The next step is careful human work that links individual bacterial strains to measurable circuit changes.”

Further research will need to confirm causality in humans, identify actionable microbial targets, and test safe microbiome-based interventions as adjuncts to existing bipolar disorder treatments.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

DaNix

Is this even true? Fecal transplants from depressed bipolar patients causing anhedonia in mice... weird. How long till we get causal proof, and why is lithium working but not fluoxetine? feels premature

bioNix

Wow didnt expect gut bugs to rewire mPFC like that. Kinda scary, kinda hopeful. If it holds up in humans, probiotics might change psychiatry, but if...

Leave a Comment