8 Minutes

Asteroid mining has swung between fevered hype and quiet skepticism over the past decade. New laboratory work led by Spain's Institute of Space Sciences (ICE-CSIC) revisits the question with hard data: which asteroids actually contain usable materials, and how feasible is extracting them in microgravity? The answer is nuanced — some bodies look promising, others less so — and the path from sample to supply chain remains steep.

Why carbon-rich asteroids matter — and why they're hard to mine

Roughly 75% of known asteroids are classified as C-type, or carbonaceous. These bodies are primitive: leftover building blocks from the early Solar System that have experienced relatively little melting or differentiation over 4.5 billion years. Because they carry organic compounds and water-bearing minerals, C-type asteroids are of strong interest for both science and in-space resource use.

But there are practical obstacles. Carbonaceous chondrite meteorites — fragments shed from C-type asteroids — represent only about 5% of meteorite finds on Earth. They are fragile and often break apart during atmospheric entry or while tumbling across a planetary surface, so intact samples are rare. That scarcity complicates the task of determining reliable, representative compositions for whole asteroids.

To address this, a team led by Dr. Josep M. Trigo-Rodríguez (ICE-CSIC / IEEC) selected and characterized samples of carbonaceous chondrites and applied high-precision mass spectrometry to quantify their elemental and mineralogical makeup. The collaborators include PhD student Pau Grèbol-Tomàs, Dr. Jordi Ibanez-Insa, Prof. Jacinto Alonso-Azcárate, and Prof. Maria Gritsevich. Their results, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, provide a clearer map of what these asteroids actually contain.

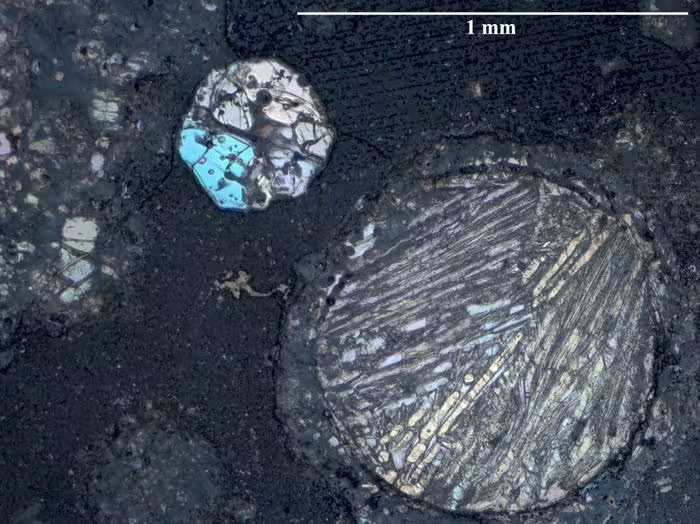

Reflected light image of a thin section of carbonaceous chondrite meteorite from NASA's Antarctic collection.

What the chemistry reveals: water, silicates and rare metals

Mass spectrometric analysis allowed the team to compare the chemical signatures of six of the most common classes of C chondrites. Key findings include:

- Water-bearing minerals are present in many carbonaceous samples. These hydrated minerals could, in theory, be a source of water for life support and propellant production.

- Certain asteroids show pronounced olivine and spinel spectral bands — signatures of silicate-rich rocks that may be easier to process than fragile, highly altered carbonaceous material.

- Overall abundances of precious metals (platinum-group elements, gold) are generally low in many carbonaceous samples, meaning that the economic case for returning bulk ore to Earth is weak in most cases.

The upshot is straightforward: not all asteroids are equal. Some types — particularly olivine- and spinel-rich bodies or specific water-rich carbonaceous asteroids — stand out as better early targets for in-space resource extraction. Conversely, undifferentiated, fragile chondritic asteroids are less attractive for large-scale mining because their material properties and low concentrations of high-value metals make extraction technically and economically challenging.

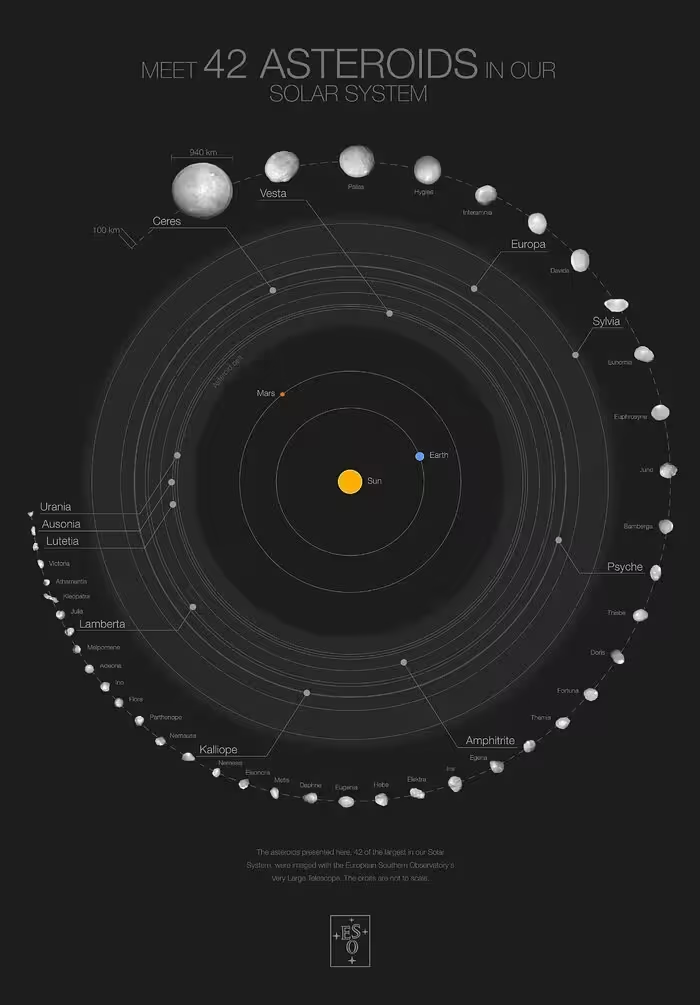

(ESO)

Practical hurdles: from microgravity collection to waste handling

Even if a target asteroid contains useful water or metals, moving from scientific sample to industrial operation is complex. The research team highlights several engineering and environmental challenges:

- Microgravity harvesting: collecting loose regolith and fractured rock in a near-weightless environment demands new large-scale capture systems and robotic tools.

- Processing and refinement: converting raw asteroid material into storable water, propellant, or refined metals requires energy, infrastructure, and processes that perform reliably off Earth.

- Waste management: mining produces tailings and contaminants. In space, poorly handled waste could interfere with spacecraft operations or create orbital debris unless mitigation strategies are adopted.

Trigo-Rodríguez and colleagues stress that while sample-return missions are critical to verify progenitor bodies, industry partners must accelerate technology development for extraction, collection and in-orbit processing. "For certain water-rich carbonaceous asteroids, extracting water for reuse seems more viable," Trigo-Rodríguez said, noting water's immediate utility as rocket propellant and life-support resource.

Scientific benefits beyond resources

Asteroid mining discussions often emphasize economics, but the scientific upside is equally compelling. Returned materials and in-situ studies improve our understanding of Solar System formation, volatile delivery to early Earth, and the evolution of small bodies. They also support planetary defense: better compositional knowledge informs models for deflecting or breaking up potentially hazardous asteroids.

"Studying these meteorites in our clean room is fascinating because of the mineral diversity they contain," said Pau Grèbol-Tomàs. "Most asteroids have relatively small abundances of precious elements, so our goal was to evaluate realistic extraction viability rather than feed science fiction fantasies."

Where missions fit into the roadmap

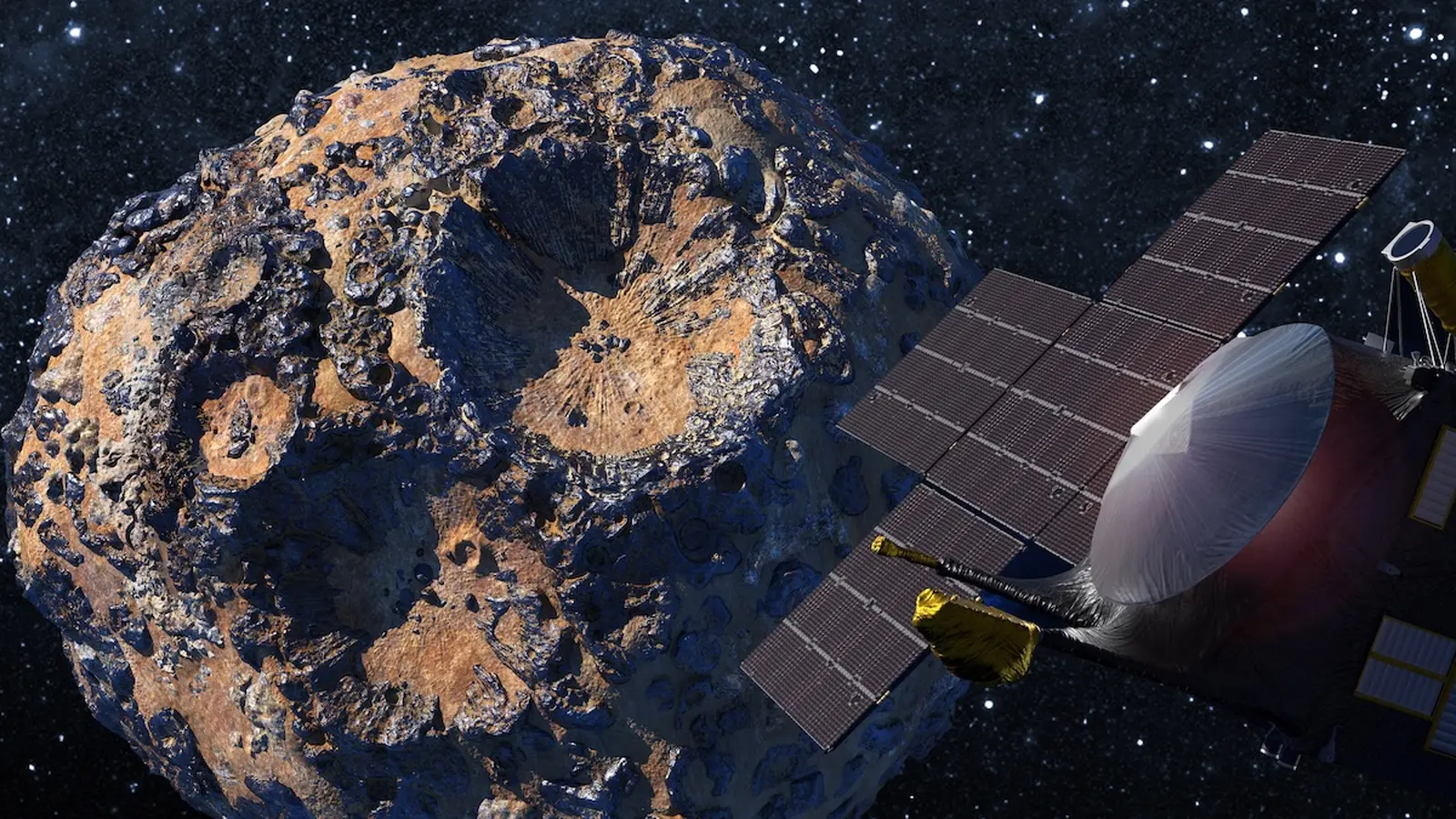

Major space agencies have already advanced the field through strategic sample-return missions. NASA's OSIRIS-REx and Japan's Hayabusa2 returned pristine samples that reshaped expectations about organic molecules and water content. China’s upcoming Tianwen-2 mission aims to rendezvous with a near-Earth asteroid and a Main Belt comet, adding more data points for scientists and engineers.

These missions do more than fill laboratory racks: they validate remote sensing techniques, test sampling hardware, and reveal heterogeneity within single targets. That heterogeneity — the fact that composition changes dramatically over small distances on an asteroid — means that scouting and high-fidelity mapping will be required before committing heavy investment to extraction infrastructure.

Economic and environmental implications

If in-space resource recovery proves practical, the implications are wide-ranging. Water and propellant produced off Earth would reduce launch mass and frequency from Earth, enabling longer crewed missions and larger robotic operations deeper into the Solar System. Manufacturing in cislunar space could lower the planetary environmental toll of terrestrial mining by moving some heavy industry off-planet.

Yet the timeline for a functional asteroid-mining industry remains long. Experts estimate decades of coordinated development: from identifying high-value targets, to deploying demonstration mining hardware, to building orbital foundries that can process raw feedstock into usable commodities.

Expert Insight

"Asteroid materials offer unique opportunities, but they don't change the laws of physics — extraction still costs energy and requires robust systems," says Dr. Lillian Hart, a fictional but realistic senior systems engineer with experience in NASA robotic missions. "The most likely near-term payoff is water for propellant and life support, not truckloads of platinum heading back to Earth. Demonstrations that show repeatable capture and processing in microgravity will be the game-changers."

Hart's point underlines the pragmatic path many researchers and companies are following: start small, prove specific use-cases (like ice-to-fuel conversion), then scale toward more ambitious material recovery if and when the economics justify it.

What comes next for research and industry?

The ICE-CSIC team's mass spectrometry results supply a critical piece of the puzzle by mapping elemental abundances across carbonaceous classes. But their conclusions also underline the need for more representative sampling of progenitor bodies. Additional sample-return missions, high-resolution spectral surveys, and coordinated technology demonstrations are required to bridge laboratory knowledge and operational capability.

For companies and agencies contemplating investment, several priority areas stand out: precision prospecting to find water-rich or olivine/spinel-bearing asteroids; development of autonomous collection and processing rigs suited to low gravity; and environmental controls for waste and byproducts. Policy, liability, and international collaboration will also shape whether asteroid resources are exploited responsibly and equitably.

Ultimately, asteroid mining remains a frontier where science, engineering and policy must converge. The ICE-CSIC study does not deliver a sudden green light for commercial exploitation, but it does sharpen the focus: water-rich and specific silicate-rich asteroids are the most promising near-term targets, while undifferentiated chondritic material presents severe technical challenges. The future will be incremental — one mission, one demonstrator, one verified target at a time.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

Marius

Feels overhyped but okay. science looks solid, economics not. Start with water for fuel, prove tech, then think big. quick thought, messy but plausible

mechbyte

is this even true? seems optimistic, what about costs, regs and the sheer engineering headache. sample bias worries me, plus tiny metal yields lol

astroset

Wow, cool data! but kinda mindblowing that water extraction seems more doable than gold... if they nail capture and processing, could actually change missions, wild

Leave a Comment