4 Minutes

New research from the University of Birmingham shows that autistic and non-autistic people move their faces in distinct ways when they express anger, happiness or sadness. These differences can cause emotional signals to be misread by both groups — not because one is wrong, but because the nonverbal "vocabulary" is different.

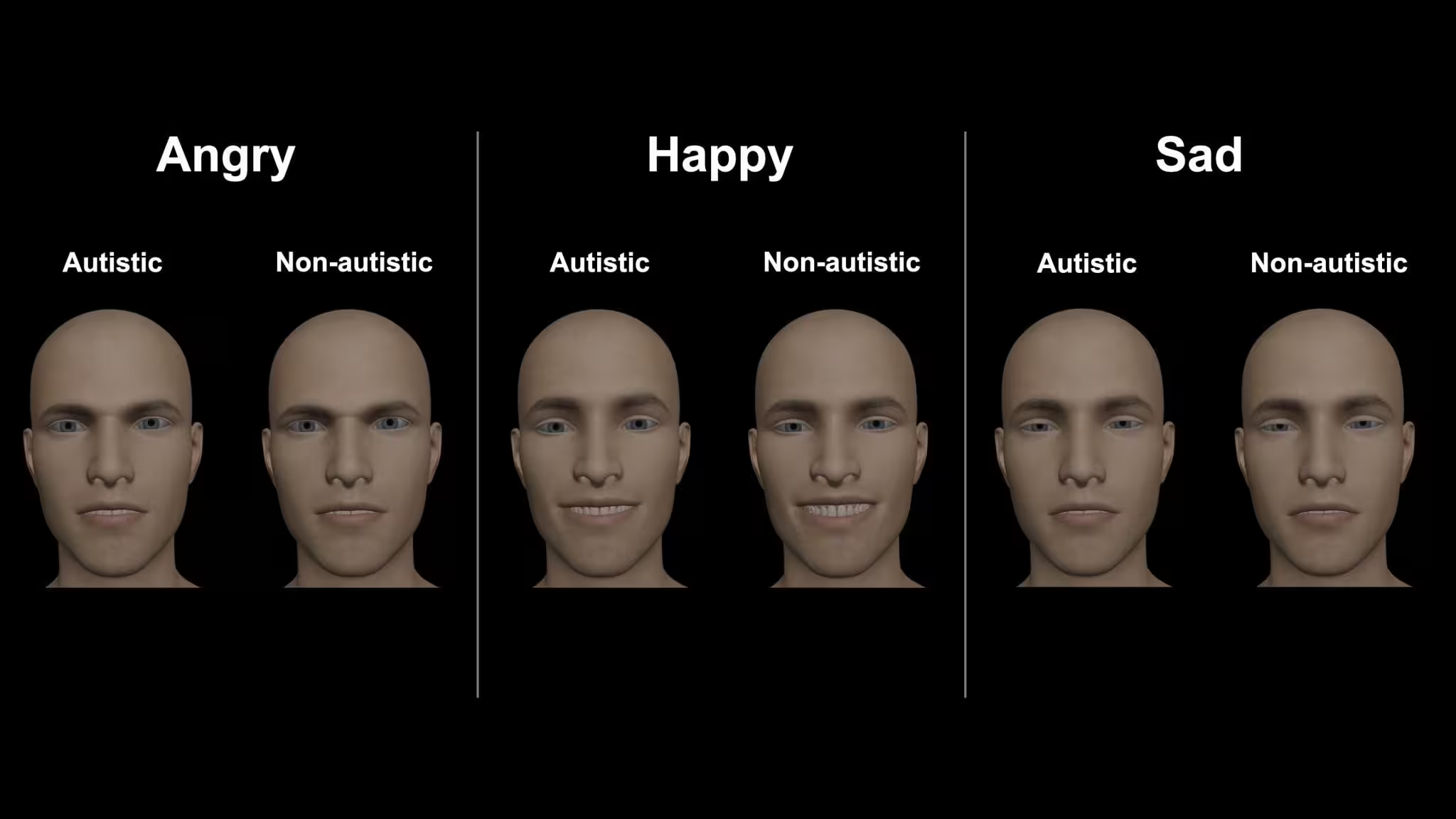

Scientists discovered that autistic and non-autistic people use their faces differently to express emotions like anger, happiness, and sadness. These differences may explain why emotional signals are often misunderstood between the two groups.

Mapping facial motion: a high-resolution look at expression

Using advanced facial motion tracking, researchers created a detailed reference of how people physically form core emotions. The study—published in Autism Research—collected nearly 5000 individual expressions from 25 autistic adults and 26 non-autistic adults, producing more than 265 million data points. That density allowed the team to move beyond simple labels and examine the fine-grained mechanics of expression: which muscles move, how quickly, and in what combinations.

How the experiment worked and what it revealed

Participants were asked to show anger, happiness and sadness in two contexts: by matching sounds and while speaking. This approach let researchers capture both posed and more spontaneous facial gestures. Analysis revealed consistent, interpretable differences in how the two groups use facial features.

Key movement differences

- Anger: Autistic participants relied more on mouth movements and less on eyebrow activity compared with non-autistic participants.

- Happiness: Smiles from autistic participants often appeared more subtle and less likely to affect the eye region — the classic "smile that reaches the eyes" was less common.

- Sadness: Autistic expressions frequently included a lifted upper lip to create a downturned look, a pattern less pronounced in non-autistic faces.

Alexithymia: a complicating factor

The team also examined alexithymia, a trait marked by difficulty identifying and describing internal feelings and commonly found alongside autism. Higher alexithymia scores correlated with less clearly defined facial signals for anger and happiness — expressions that appeared mixed or ambiguous. That suggests some variability in expression is related not only to autism itself, but to individual differences in emotional awareness.

Why misreading goes both ways

Lead researcher Dr. Connor Keating (now at the University of Oxford) and colleagues argue the issue is reciprocal. It’s not only that autistic people sometimes struggle to recognize non-autistic expressions — non-autistic observers also have trouble interpreting autistic facial cues. The study points to differences in both the appearance and the smoothness of expression formation as likely culprits. In effect, people may be speaking different nonverbal dialects.

Implications for communication, technology and support

These findings matter beyond academic interest. For clinicians and therapists, understanding diverse facial patterns can improve diagnostic clarity and reduce misinterpretation during assessments. For designers of emotion-recognition software and social robotics, the results highlight the risk of bias when training algorithms on a narrow range of faces. And for everyday social interaction, recognizing that expressions can be different but meaningful may encourage more patient, two-way efforts to bridge understanding.

What’s next?

The authors are already exploring whether training or context can reduce miscommunication, and whether awareness campaigns might improve mutual recognition between autistic and non-autistic people. As Professor Jennifer Cook from the University of Birmingham notes, treating differences as alternative — not deficient — systems of expression opens new pathways for research, inclusion and technology that respects diversity in emotion signaling.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment