6 Minutes

Invisible, nanoscale bubbles released by cells are emerging as key players in how cancer travels through the body. By recreating those tiny messengers in the lab, researchers hope to both map metastasis and deliver drugs more precisely to tumours — potentially stopping cancer in its tracks.

What are these tiny bubbles and why they matter

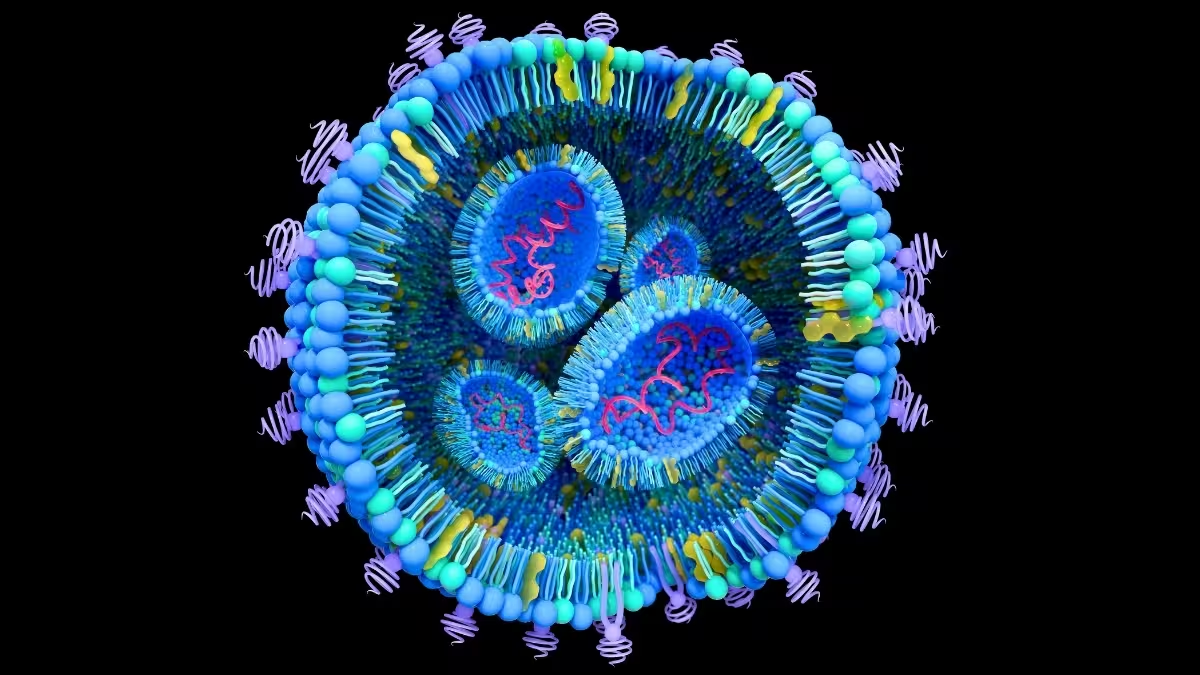

Every cell secretes extracellular vesicles — membrane-wrapped particles often under 100 nanometres across that carry lipids, proteins and snippets of genetic material. In healthy biology they shuttle signals between cells. In cancer, however, these vesicles can act as covert couriers that prime distant tissues, remodel microenvironments and even reprogram healthy cells to support tumour growth. This cascade of events is central to metastasis, the process by which cancer spreads from a primary tumour to organs such as the liver or lungs.

Understanding the composition and route of these vesicles is essential. But isolating and characterizing natural extracellular vesicles from blood or tissue is slow, technically demanding and variable. That bottleneck is why teams in bioengineering and cancer biology have turned to synthetic analogues: liposomes and other lipid nanoparticles that mimic the form and function of natural vesicles.

How researchers recreate cancer’s messengers

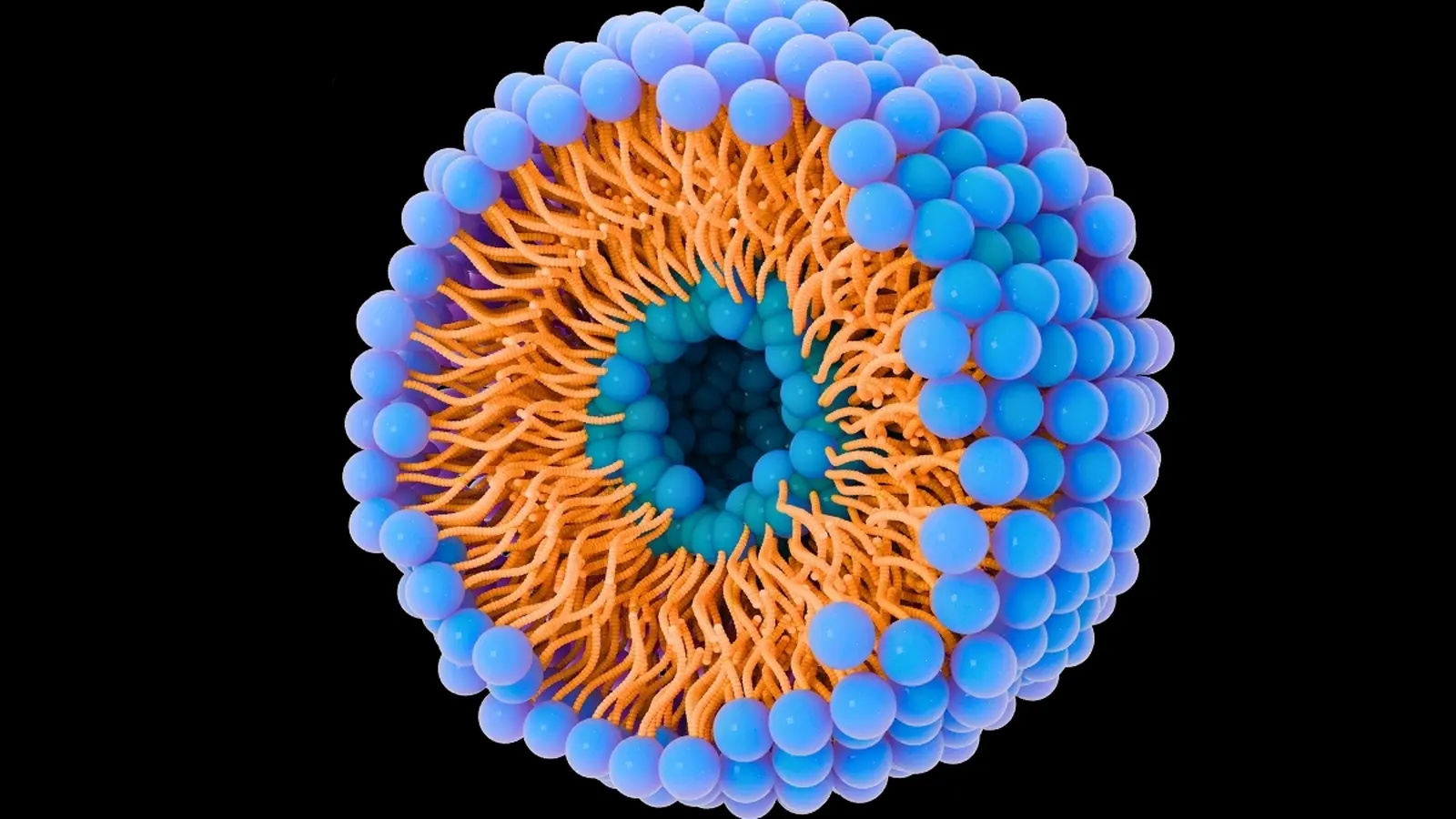

At École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS), an interdisciplinary group led by engineers is engineering liposomes using micromixers — microfluidic devices that rapidly combine lipid, protein, aqueous and alcoholic solutions to form uniform nanoparticles. By tuning the ratio of lipids, the surface charge and the protein content, the lab produces particles that resemble extracellular vesicles in size and behavior.

These artificial vesicles are labelled with fluorescent markers, incubated with cultured cancer cells and filmed in real time. The experiments track how quickly and how much of the nanoparticle population is taken up by cells, and which biochemical features drive uptake. In short, the closer a liposome’s size, charge and surface proteins match the natural vesicle, the more likely a cancer cell will absorb it.

That fidelity matters for two reasons. First, a faithful mimic helps scientists map how cancer-derived vesicles traffic to specific organs and what signals they deliver to resident cells. Second, it opens a route to use those same carriers as targeted drug shuttles — turning a pathology into a delivery platform.

From lab models to therapy ideas

Current work has reached a ~50% efficiency for encapsulating proteins inside lab-made liposomes; the team’s goal is to push that toward 90% to better mirror natural extracellular vesicles. Once formulation parameters are refined, the protocol moves from cell cultures to animal models — planned rat studies to validate transport and therapeutic payload delivery in vivo.

There are several therapeutic strategies under exploration. One is to load liposomes with established chemotherapeutics, such as paclitaxel, which already shows improved delivery and tolerability when formulated in lipid carriers. Another is to encapsulate biologically active natural compounds: curcumin (from turmeric) and related molecules have shown anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects in many studies, and packaging curcumin in liposomes increases its bioavailability and tumour-targeting potential.

Beyond small molecules, liposomes can carry nucleic acids or antibodies. Short DNA fragments, siRNA, or antibody fragments can be ferried to tumours to silence oncogenes, sensitize cancer cells to drugs, or flag malignant cells for immune clearance. These multi-modal approaches are already part of the expanding toolbox of nanomedicine and have reached clinical use in some contexts.

What the experiments are revealing

Real-time imaging shows that particle size and surface chemistry are primary determinants of uptake. Particles that replicate the diameter and electrostatic profile of natural vesicles are internalized more efficiently by liver cancer cells in vitro, suggesting that organ-specific metastasis may be mediated in part by the physical identity of vesicles in circulation.

That insight reframes a long-standing question in metastasis research: is organ targeting driven mainly by tumour-secreted molecular signals, or do physical delivery systems — the vesicles themselves — play a gating role? The answer appears to be both. The biochemical cargo instructs the target tissue, while the vesicle’s physical attributes determine whether it gets there in sufficient quantity.

Potential clinical implications

- Prevention of metastasis: If vesicle-mediated priming of distant organs is blocked, metastases may never establish. Liposome-based decoys or inhibitors could intercept harmful vesicles before they act.

- Targeted treatment: Liposomes designed to mimic tumour vesicles could deliver cytotoxic drugs or gene therapies selectively to metastatic niches, reducing systemic toxicity.

- Biomarkers and diagnostics: Characterizing vesicle composition in blood may offer early warning signs of metastatic risk or therapy response.

These are measurable goals rather than distant dreams. Several nanoformulations are already in clinical use, and ongoing studies refine particle design to increase specificity, reduce immune clearance and optimize payload release.

Expert Insight

"Reproducing the body's own communication packets gives us both a microscope and a map," says Dr. Elena Marquez, a fictional biomedical engineer who studies nanocarriers. "When a lab-made liposome behaves like a cancer-derived vesicle, we can observe the delivery path and then design interventions that either block harmful signals or use the same path to deliver precisely targeted therapies."

This perspective underlines the dual value of the approach: deepening fundamental knowledge about metastasis while accelerating translational therapies.

Challenges and next steps

Major hurdles remain. Scaling uniform particle production, ensuring stable protein encapsulation, avoiding rapid clearance by the immune system and validating safety in animal models are all active areas of work. Regulatory pathways for complex biologic–nanoparticle hybrids are also still maturing, which can slow clinical translation.

Nevertheless, the incremental findings reported by interdisciplinary teams are converging: extracellular vesicles are not just epiphenomena of disease but active agents in cancer progression. And by copying them, researchers may gain the leverage needed to prevent or treat metastasis more effectively.

Moving from cell culture to animal models is the critical near-term milestone for the ÉTS–McGill collaboration. If successful, those studies could pave the way for human trials of liposome-based interceptors and targeted delivery systems — technologies that could change outcomes for patients at high risk of metastatic disease.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment