5 Minutes

New research links mating spikes and mouth teeth in ratfish

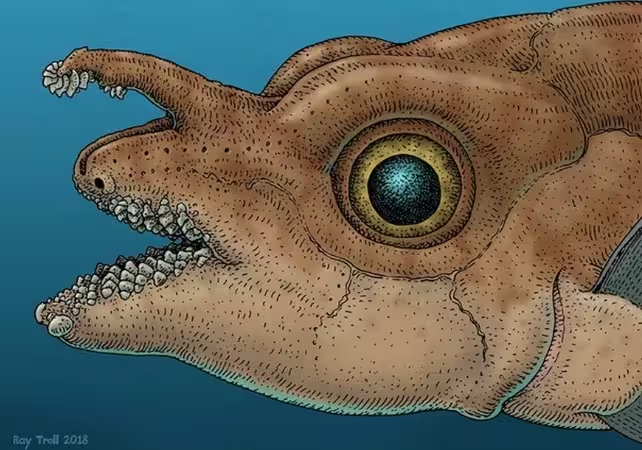

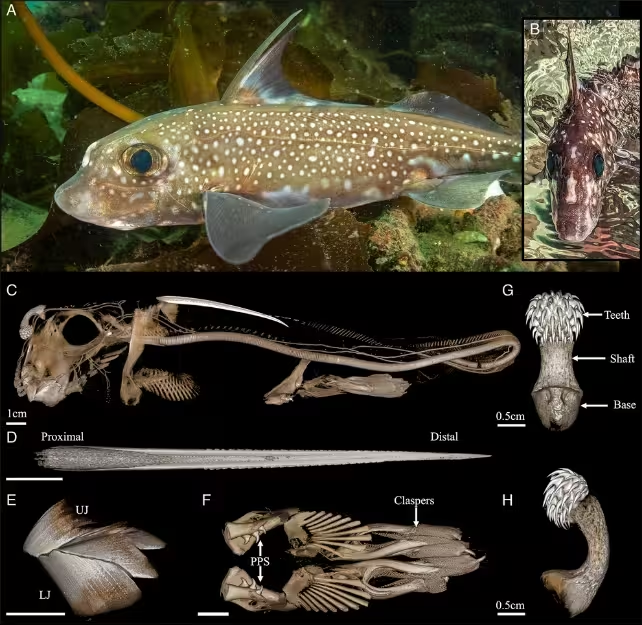

A recent developmental genetics study reports that the specialized forehead teeth used during mating in some cartilaginous fishes are genetically derived from the same developmental programs that build oral teeth. These forehead structures, called tenacula, resemble dental elements in their shape and composition but are deployed on the head rather than inside the mouth. The work documents how an ancestral tooth-making genetic network can be repurposed to form spiny, tooth-like projections in non-oral locations — a striking example of evolutionary reuse.

Scientific background and developmental context

Teeth are traditionally associated with the jaws and oral cavity, formed from interactions between epithelial and mesenchymal tissues and patterned by a conserved set of genes. For decades, paleontologists and evolutionary biologists debated how teeth first appeared in vertebrates. Two primary hypotheses emerged: an 'inside-out' model, in which internal pharyngeal tooth-like structures migrated into the mouth, and an 'outside-in' model, in which dermal denticles on the skin moved inward to become oral teeth.

The new study examines the spotted ratfish and traces the genetic and developmental signatures of forehead tenacula. Researchers identify overlapping gene expression and developmental mechanisms between oral teeth and these mating-related spikes, indicating that the same odontogenic toolkit can be redirected to build different structures in different anatomical positions. This finding helps reconcile the two historical hypotheses by demonstrating that tooth-building programs can shift their deployment across tissues and evolutionary time.

Key discoveries and evolutionary implications

- Repurposing of developmental modules: The study shows that genetic pathways normally producing oral teeth can be co-opted to produce external spines used in mating, supporting the idea that evolution frequently reuses existing genetic circuits to create novel morphology.

- Multiple evolutionary routes: Evidence suggests both inward and outward origins for tooth-like structures are plausible across different lineages. Some species may have evolved oral teeth from modified dermal denticles, while others may have invited pharyngeal tooth-like structures forward into the mouth. The new data indicate these are not mutually exclusive scenarios.

- Broader distribution of 'teeth': By demonstrating that tooth-building genes can operate outside the jaw, the study argues that teeth or tooth-like elements may be more widespread in vertebrate anatomy than previously recognized. Researchers predict that additional discoveries of extra-oral teeth could follow as more taxa are examined with developmental genetic methods.

The authors frame this as an example of evolutionary flexibility: structures that originally evolved for feeding can be redeployed for reproductive or defensive roles, producing novel morphologies without requiring entirely new genetic inventions. As one of the study leads notes, the more comparative and developmental work performed across vertebrates, the more likely scientists are to identify tooth-like structures beyond the jaw.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Alvarez, evolutionary developmental biologist, comments: 'This paper neatly illustrates a core principle of evolutionary developmental biology: conserved genetic toolkits can be spatially and temporally redeployed to generate new anatomical features. Finding that forehead tenacula share developmental signatures with oral teeth opens the door to reinterpreting many spiny elements in the fossil record and living taxa as modified dental structures.'

Practical implications include new approaches to interpreting fossil odontodes and to studying how gene regulatory networks change spatially during development. The work also guides future surveys of vertebrate taxa for unexpected tooth-like structures, using both embryology and gene-expression profiling.

Conclusion

The study of spotted ratfish forehead teeth demonstrates that tooth-making genetic programs are more flexible than once believed. By showing that oral tooth pathways can be redirected to produce mating-related spines, researchers provide evidence that both 'inside-out' and 'outside-in' scenarios may have contributed to tooth evolution across different lineages. This research underscores evolution's tendency to repurpose existing developmental systems, and it suggests a broader, richer distribution of tooth-like structures among vertebrates than previously recognized.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment