8 Minutes

New milestone: tracking a black hole's three-dimensional kick

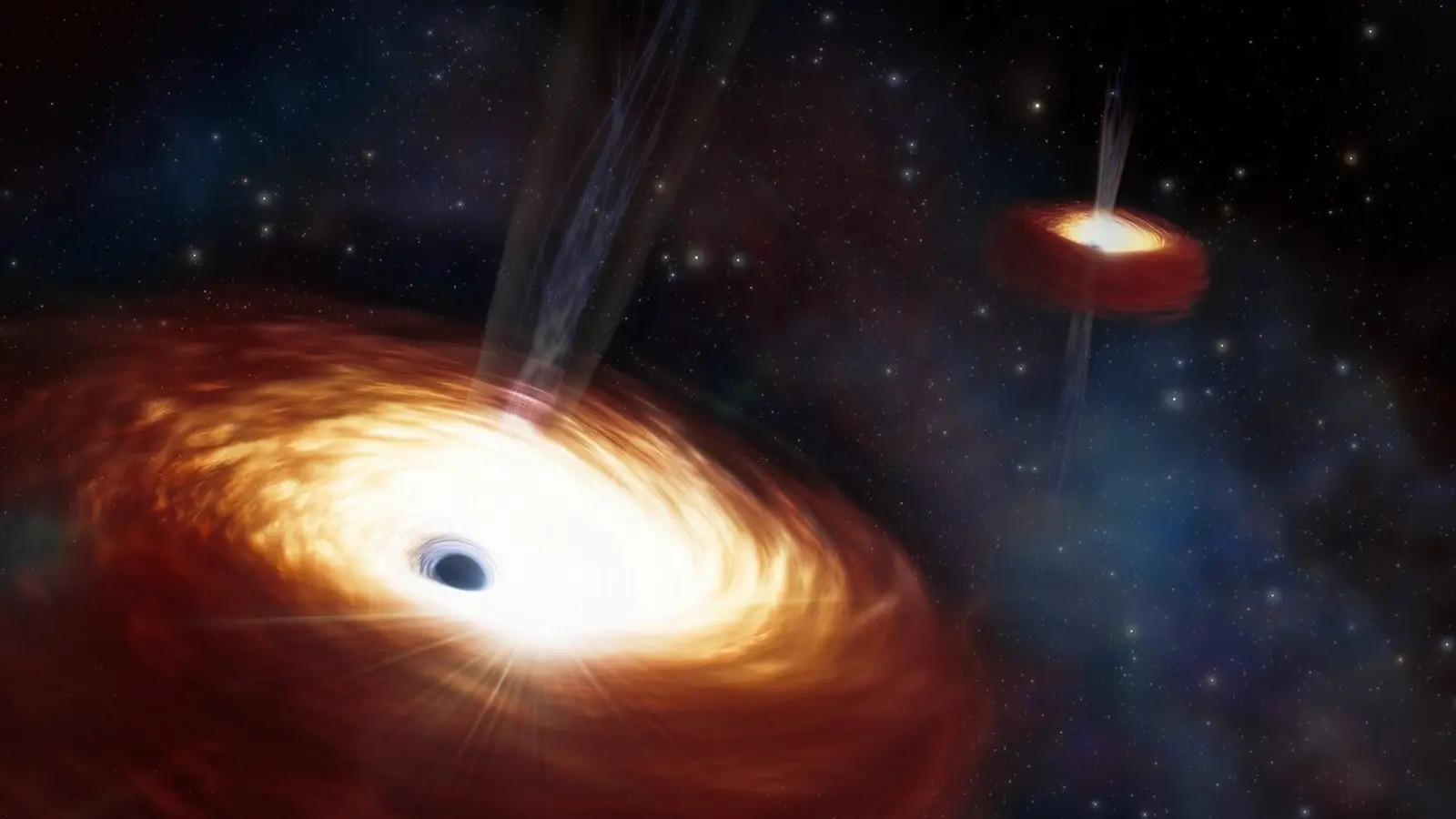

A team led by the Instituto Galego de Física de Altas Enerxías (IGFAE) at the University of Santiago de Compostela has reconstructed both the speed and direction of a remnant black hole produced in a binary black-hole merger. The result, published in Nature Astronomy, uses data from the GW190412 event and demonstrates that gravitational-wave astronomy can reveal not only that violent mergers occur, but also the full three-dimensional motion — or recoil — of the resulting object.

Scientific background: gravitational waves and black-hole kicks

Gravitational waves (GWs) are propagating ripples in spacetime predicted by Albert Einstein in 1916. They are generated by accelerating masses, with the strongest signals produced by extreme events such as binary black-hole mergers, neutron-star collisions, and core-collapse supernovae. Because some of these sources emit little or no light, gravitational-wave detectors provide a complementary window into the Universe.

The first direct detection of gravitational waves, GW150914, was announced in 2015 by the Advanced LIGO observatories. That landmark observation confirmed the reality of compact-object mergers and opened gravitational-wave astronomy as a new observational discipline. Since GW150914, nearly 300 candidate events have been reported by the LIGO–Virgo network, enabling population studies and novel tests of general relativity.

One striking outcome of asymmetric black-hole coalescences is recoil, often described as a gravitational "kick." If the gravitational-wave emission from a merger is anisotropic — that is, stronger in some directions than others — conservation of momentum imparts a velocity to the merged remnant. Recoil speeds can span tens to thousands of kilometers per second; in some cases the kick can be large enough to eject a black hole from its host star cluster or even from a galaxy.

GW190412: an unequal-mass merger that carried a measurable kick

The analysis focused on GW190412, detected in April 2019 during the third observing run (O3) of Advanced LIGO and Virgo. GW190412 is notable because it involved black holes of unequal mass and exhibited clear contributions from higher-order multipole radiation — a kind of "richer" gravitational-wave signal. Those features make it possible to constrain the orientation and structure of the waveform more tightly than for more symmetric systems.

By modeling how the waveform changes with observer position, the team reconstructed the remnant's velocity vector relative to Earth and to intrinsic directions of the binary system (for example, the orbital angular momentum). The result shows the remnant moved faster than 50 km/s — fast enough, the authors note, to escape a dense globular cluster — and provides a full 3D description of the kick a few seconds after merger.

How the measurement works

Gravitational-wave signals are complex superpositions of modes (mathematical components of the wave analogous to musical notes). When different modes contribute significantly, the relative amplitude and phase of each mode depend on the viewing angle. This dependence allows analysts to infer where the observer is located relative to the source. The IGFAE-led team applied waveform models that include these higher-order modes and combined them with parameter-estimation techniques from Bayesian inference. In the words of lead author Prof. Juan Calderon-Bustillo: "Black-hole mergers can be understood as a superposition of different signals, just like the music of an orchestra... audiences located in different positions around it will record different combinations of instruments, which allows them to understand where exactly they are around it."

The strategy relies on three measured ingredients: (1) the relative contributions of waveform modes that encode viewing-angle information; (2) the inferred masses and spins of the binary components, which determine the expected recoil velocity in general relativity; and (3) careful statistical modeling to combine observational uncertainty with theoretical predictions.

Key discoveries and implications

The main discovery is that a gravitational-wave signal alone can yield a full three-dimensional reconstruction of a remnant black hole's motion at cosmological distances. Dr. Koustav Chandra (Penn State), a co-author, summarized the significance: "This is one of the few phenomena in astrophysics where we're not just detecting something—we're reconstructing the full 3D motion of an object that's billions of light-years away, using only ripples in spacetime. It's a remarkable demonstration of what gravitational waves can do."

Practical implications include:

- Astrophysical retention and ejection: A recoil above ~50 km/s can unbind a black hole from low-mass stellar systems such as globular clusters or from the central regions of dwarf galaxies. This affects predictions for merger rates in dense environments and for the growth history of massive black holes.

- Multi-messenger searches: Measuring recoil direction helps assess the visibility of any electromagnetic flare produced when the remnant traverses dense gas. As co-author Samson Leong (CUHK) notes, "Because the visibility of the flare depends on the recoil's orientation relative to Earth, measuring the recoils will allow us to distinguish between a true GW–EM signal pair that comes from a BBH and a just random coincidence." In active galactic nuclei (AGN) disks or other dense environments, a kicked remnant may perturb surrounding gas and produce transient electromagnetic emission.

- Population and cosmological consequences: Accurate recoil measurements feed into models of black-hole demographics, retention fractions in clusters, hierarchical merger scenarios, and the expected gravitational-wave background.

The result also validates a method proposed in 2018 by the same group, which showed that current ground-based detectors could measure kicks from signals with significant higher-mode content — earlier approaches had assumed that space-based detectors like LISA, sensitive to lower-frequency sources, would be required.

Related technologies and future prospects

This measurement underscores the importance of detector sensitivity and waveform modeling. Continued upgrades to LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA will increase the number and quality of detected events, improving the odds of capturing additional systems with measurable higher modes. Future detectors such as LIGO Voyager, the Einstein Telescope, Cosmic Explorer, and the space-based LISA will expand the accessible mass and distance ranges and directly probe regimes where kicks can be even larger or lead to observable electromagnetic counterparts.

Combining gravitational-wave measurements with electromagnetic surveys and time-domain observatories will be crucial to confirm flare associations and to study the environments in which mergers occur. Coordinated programs between GW facilities and wide-field optical, infrared, X-ray, and radio observatories will sharpen the search for kick-driven transients.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Singh, theoretical astrophysicist at the Institute for Gravitational Physics, offers contextual perspective: "This work marks a pivotal step for gravitational-wave astronomy. By extracting the remnant's full velocity vector from a single event, the team demonstrates that we can move beyond detection to kinematic reconstruction. That capability will let us probe how black holes populate different astrophysical environments and test scenarios for repeated mergers in dense clusters. On the observational side, detecting more high-mode signals will let us map the distribution of kick velocities across the population, which has direct consequences for black-hole growth and retention in galaxies."

Dr. Singh adds a technical note: "Accurate waveform models that include higher-order multipoles and precession are essential. The progress in waveform development and parameter-estimation methods over the past decade made this measurement possible today."

Conclusion

The IGFAE-led analysis of GW190412 provides the first full three-dimensional measurement of a black-hole recoil velocity, demonstrating that gravitational-wave data can reveal both the magnitude and direction of a remnant's kick. With a measured speed exceeding 50 km/s, the remnant of GW190412 exemplifies how asymmetric mergers can alter the fate of black holes—potentially ejecting them from clusters and shaping their astrophysical environments. Beyond the immediate result, this work illustrates the expanding capabilities of gravitational-wave astronomy: not only to detect extreme events, but to reconstruct their dynamics in detail and to inform multi-messenger searches for electromagnetic counterparts. As detector sensitivity and waveform models continue to improve, similar measurements should become routine, offering new constraints on black-hole formation channels, hierarchical mergers, and the interplay between compact objects and their surroundings.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment