8 Minutes

New deep‑sea snailfishes discovered off California

MBARI’s cutting-edge underwater tools are uncovering unique species that inhabit the deep ocean. In 2019, researchers observed a pink snailfish gliding just above the seafloor that did not match any known species. Follow-up research has now confirmed that this fish is a newly identified species, the bumpy snailfish (Careproctus colliculi).

The discovery was published by researchers at the State University of New York at Geneseo (SUNY Geneseo) in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Montana and the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa in the journal Ichthyology and Herpetology. The paper formally describes three previously undocumented snailfishes collected from abyssal depths off the coast of Central California.

The bumpy snailfish (Careproctus colliculi) has a distinctive pink color, pectoral fins with long fin rays, and a unique bumpy texture.

What the team found: three new Liparidae species

Researchers identified and described three new members of the family Liparidae (snailfishes): the bumpy snailfish (Careproctus colliculi), the dark snailfish (Careproctus yanceyi), and the sleek snailfish (Paraliparis em). Each species displays morphological traits and genetic sequences that distinguish it from known congeners.

The bumpy snailfish stood out in remotely operated vehicle (ROV) video as a small, pink fish hovering above the abyssal plain. The specimen later collected for laboratory work was an adult female measuring 9.2 centimeters (3.6 inches). It is characterized by a rounded head with proportionally large eyes, broad pectoral fins whose uppermost rays are elongated, and a distinctive granular or bumpy skin texture.

The dark snailfish is uniformly black with a rounded head and a horizontal mouth. The sleek snailfish is elongate and laterally compressed, black in color, lacks a ventral suction disk (a common feature in many liparids), and has a strongly angled jaw. The species epithet for Paraliparis em honors Station M, the long‑term abyssal research site that has supported decades of deep‑sea monitoring and discovery.

How the discoveries were made: methods and tools

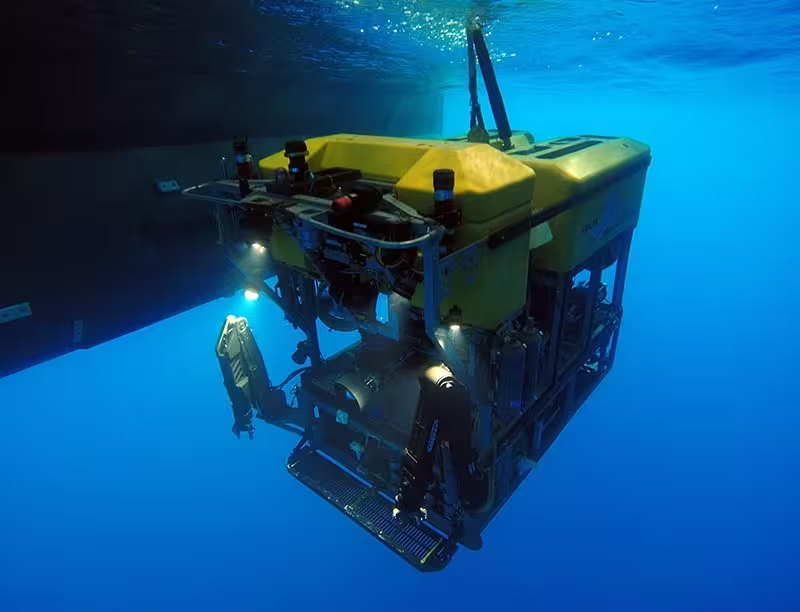

Operated by a team of scientists and pilots aboard a research vessel at the surface, MBARI’s ROV Doc Ricketts is a robotic submersible equipped with advanced cameras and scientific instruments for exploring the ocean’s midnight zone and abyssal seafloor.

The investigation combined in situ observations, specimen collection, and laboratory analysis. MBARI’s ROV Doc Ricketts provided high‑definition video that allowed scientists to detect and track the unusual swimmer in Monterey Canyon at 3,268 meters (10,722 feet). Additional specimens—the dark and sleek snailfishes—were recovered in 2019 with the human‑occupied submersible Alvin near Station M at ~4,000 meters (13,100 feet).

In the laboratory the team employed an integrative taxonomy workflow: high‑resolution imaging, microscopy, micro‑computed tomography (micro‑CT) scans, careful morphometrics, and DNA sequencing. Micro‑CT allowed detailed 3D views of internal skeletal structure without damaging fragile specimens; microscopy documented external details such as dermal texture and fin ray counts. Genetic data placed the new specimens within the Liparidae phylogeny and confirmed that they are distinct species. The research team made CT scan datasets available through MorphoSource and submitted genetic sequences to GenBank (PV300955–PV300957 and PV298545–PV298546).

Many deep-sea snailfishes are hard to identify from video alone. MBARI researchers have observed a snailfish that appears to be the newly described slender snailfish (Paraliparis em), but without collecting a specimen for closer analysis, we cannot be sure.

Biology and adaptations of snailfishes

Snailfishes (family Liparidae) are a diverse group of benthic and benthopelagic fishes known for their soft, often gelatinous bodies, large heads, and reduced ossification—traits that help them cope with high hydrostatic pressure and low food availability in deep waters. Many possess a ventral adhesive disk formed from modified pelvic fins; this structure can be used to cling to substrates or to hitch rides on larger animals such as crabs. Other species lack the disk and are more actively swimming.

More than 400 species of snailfish have now been described worldwide. They inhabit a remarkable range of environments, from coastal tide pools to hadal trenches. Indeed, the deepest recorded fish is a snailfish, demonstrating the family’s exceptional capacity to adapt to extreme pressure, near‑freezing temperatures, and perpetual darkness. Research into these fishes integrates taxonomy, functional morphology, and physiology to explain how organ systems, buoyancy control, and skeletal features minimize energy costs and maintain function under crushing pressure.

Scientific context and implications

The three new species add to a long list of discoveries from MBARI and its research partners. Over the past decades MBARI teams have documented hundreds of previously unknown deep‑sea animals, and Station M in particular supports a time series of abyssal ecological data spanning roughly 30 years. That dataset has been critical for understanding long‑term changes in benthic communities, carbon fluxes, and the connection between surface climate variability and deep‑sea ecosystems.

Haddock’s encounter is the only confirmed observation of the bumpy snailfish, so the full geographic distribution and depth range of this species remain unknown. However, a review of MBARI’s video archive suggests similar individuals may have been observed off Oregon in 2009 and misidentified as the bigtail snailfish (Osteodiscus cascadiae). Expanding records through targeted sampling and archival video analysis will be essential to map distributions, assess population sizes, and determine ecological roles.

Documenting deep‑sea species has practical conservation implications. Deep habitats are increasingly exposed to human pressures including climate change, shifts in organic matter export, plastic pollution, and proposals for deep‑sea mining. Establishing taxonomic baselines and understanding species’ life histories are prerequisite steps for any policy or management measures intended to protect abyssal biodiversity.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Moreno, Deep‑Sea Ecology Fellow, Marine Biodiversity Institute (fictional), comments: "Discoveries like these underscore how little of the deep ocean we truly know. Integrative approaches—combining video, specimens, and genomic data—are the only reliable way to identify cryptic species in abyssal environments. Each new species provides a data point on how life adapts to extreme pressure and low energy availability, and improves our ability to detect ecological change over time."

This commentary reflects a realistic perspective shared by many deep‑sea researchers: documenting species richness and functional traits at depth is both a scientific priority and a necessary step toward conservation planning.

Data sharing, collaboration and future prospects

MBARI emphasizes open science: video footage, specimen records, CT scans, and genetic data are archived and shared with taxonomists and other researchers globally. Collaborative networks between institutions—such as SUNY Geneseo, the University of Montana, the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and MBARI—amplify taxonomic expertise and accelerate species descriptions.

Future research priorities for these and other deep‑sea taxa include targeted surveys to better define geographic ranges, population genetic studies to explore connectivity among abyssal basins, physiological experiments to test tolerance to temperature and oxygen change, and ecological studies to identify diet and trophic interactions. Technological advances—autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), improved deep‑sea imaging, environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling, and higher‑throughput genomic sequencing—will expand detection and identification capabilities in the coming years.

Conclusion

The formal description of the bumpy snailfish (Careproctus colliculi) and two additional snailfishes from California’s abyssal plains highlights the deep sea’s persistent capacity for surprise. These discoveries rest on a combination of advanced oceanographic tools, long‑term monitoring sites, and interdisciplinary taxonomic work. Beyond adding new names to the tree of life, documenting deep‑sea biodiversity establishes the baselines necessary to recognize change and to inform future conservation and management decisions for the ocean’s largest habitat.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment