8 Minutes

Heat outweighs shaking in small-scale quakes

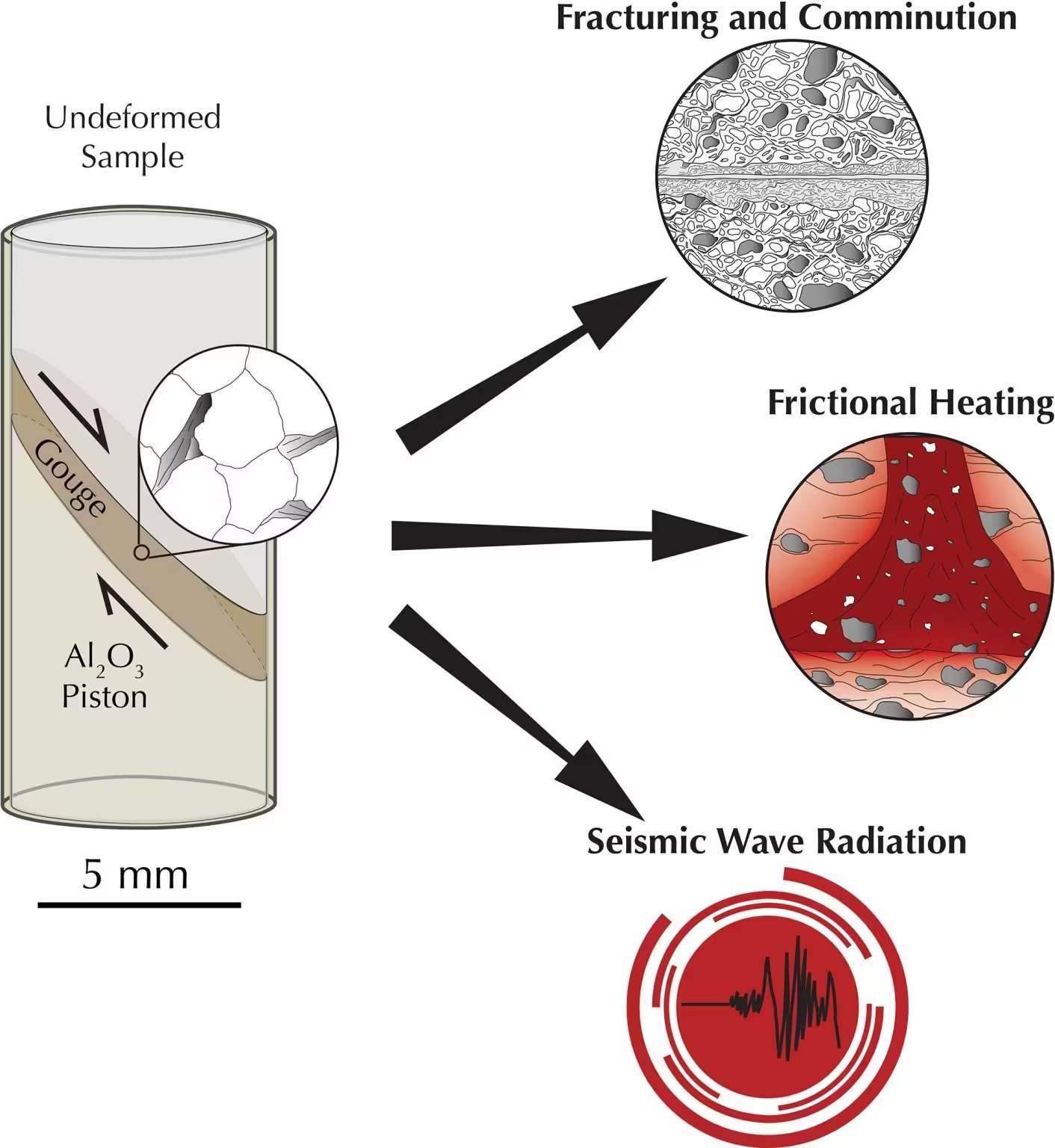

Laboratory experiments at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology show that most of the energy released during earthquake-like slip converts to heat rather than ground motion. Using controlled, microscale faulting experiments on crushed granite, researchers measured the complete energy budget of tiny, sudden slips. Their results indicate that roughly 80% of the released energy becomes frictional heat near the slip plane, about 10% produces seismic vibrations analogous to ground shaking, and less than 1% goes into creating new rock surface area through fracturing and comminution.

Those proportions are not fixed: the past deformation history of the tested materials strongly influences how energy is partitioned. Rocks that have been previously deformed can behave differently — absorbing more or less energy as heat, motion, or breakage. The experiments reproduce extreme transient temperatures, brief frictional melting, and rapid slip speeds that mirror physical processes inferred for natural earthquakes, offering new constraints on how faults evolve and how seismic hazard might be assessed.

Measuring earthquake energy in the laboratory

Directly observing and quantifying how an actual earthquake allocates energy between seismic waves, heat, and rock damage is nearly impossible in situ. To overcome that limitation, the MIT team designed repeatable lab experiments that simulate the mechanical and thermal physics of seismic slip on a controlled scale. Samples were prepared to mimic the fine-grained fault zone materials found in the seismogenic layer of continental crust, where most crustal earthquakes nucleate (roughly 10 to 20 km depth).

The experimental protocol combined several specialized techniques to capture complementary aspects of each micro-event. Researchers crushed granite into a powder and blended it with a much finer powder containing magnetic particles. These magnetic inclusions act as an internal temperature recorder because their magnetization changes when exposed to high temperature. Each powdered sample, only about 10 square millimeters in area and 1 millimeter thick, was enclosed in a gold jacket and placed between two pistons that press the sample to stresses representative of the seismogenic zone.

To record dynamic motion during slip, the team developed and attached custom piezoelectric sensors at the ends of the sample assembly. Those sensors measure short-duration pulses that represent seismic-like acceleration and displacement at the sample scale. After a controlled failure event, scientists decoded the magnetic particle signal to estimate peak temperature, examined the sample with scanning electron microscopy to document grain breakage and glass formation, and combined sensor data with numerical models to infer the partition of energy into heat, shaking, and comminution.

Why magnetic particles and gold jackets?

The magnetic powder is a form of thermomagnetic recorder: heating and cooling associated with rapid slip alter the particles' magnetization in a way that can be measured after the experiment. The gold jacket provides a chemically inert, conductive seal that preserves the sample geometry and limits oxidation during high-temperature transients. This integrated approach lets researchers reconstruct peak temperatures that lasted for microseconds and correlate those thermal excursions with mechanical measurements of slip and stress drop.

Key findings: frictional heating, melting, and rapid slip

Across dozens of micro-rupture experiments, the dominant energy sink was frictional heating close to the slip surface. On average, about 80% of the released mechanical energy was deposited as heat within the slipping zone. Seismic-like motion accounted for roughly 10% of the energy budget, while the energy required to break grains and create new surface area was consistently small, typically under 1% of the total.

In some tests the heating was intense and abrupt. The team measured transient temperature rises from ambient to roughly 1,200 degrees Celsius within microseconds, sufficient to partially or fully melt the fault material. When melted material resolidified rapidly it formed a glassy, smooth layer that looks very similar to frictional melt products seen in natural faults. In a representative case the researchers observed a slip of near 100 microns that, given the very short duration, implies local slip velocities on the order of 10 meters per second — high speed but limited spatially and temporally.

Those observations tie laboratory-scale physics to field evidence: the glassy textures and melt veins sometimes found in exhumed faults, commonly called pseudotachylytes, are compatible with frictional melting during seismic slip. The experiments therefore bridge the gap between microphysics and geological markers of past earthquakes.

Implications for seismic hazard assessment and earthquake models

If similar energy partitioning occurs in nature, faults may absorb far more of their mechanical energy as local heating and structural damage than as long-range seismic radiation. That means the fraction of energy that radiates as damaging ground shaking could be only a small portion of the total release. Understanding that split is crucial when estimating how much shaking a particular rupture might produce and how slip modifies the fault zone for future events.

The experiments also highlight the importance of deformation history. Rocks that have been previously sheared, heated, or fractured develop altered textures and mineral assemblages that change frictional strength, permeability, and how energy dissipates during future slips. In practice this suggests that seismic hazard models should account for fault zone maturity and prior slip history, not just present stress levels.

From an observational perspective, laboratory thermometry methods may provide a route to infer past energy budgets in natural faults. For instance, where pseudotachylytes or glassy striations are preserved, their presence and microstructure could record past episodes of intense, thermally concentrated slip. Combining field observations with lab-calibrated relationships between heating, slip, and radiated energy can improve reconstructions of ancient earthquakes and inform probabilistic forecasts.

Limitations and prospects for scaling to natural earthquakes

Lab quakes are intentionally simplified: they isolate key physical processes at a scale where measurements can be precise and reproducible. The Earth is orders of magnitude larger and more heterogeneous, so direct scaling requires caution. Factors such as pore fluid pressure, three-dimensional fault geometry, kilometer-scale stress gradients, and long-duration dynamic rupture processes are not fully reproduced in microscale experiments.

Nevertheless, the integrated measurement approach used by the MIT-led team — combining thermomagnetic recording, high-bandwidth dynamic sensing, microscopy, and modeling — provides one of the most complete experimental views of earthquake-like rupture physics to date. These controlled studies help parametrize and validate numerical rupture models and provide physical constraints for how heat, fracture, and radiation interact during slip.

Expert Insight

Dr. Laura Hammond, a fictional geophysicist and science communicator with experience in fault mechanics, comments: 'These experiments underscore that the processes at the slipping surface are intensely local and energetic. If most energy is dissipated as heat, then fault strength evolution and thermal alteration may be more important for earthquake sequences than we have assumed. Incorporating lab-derived energy partitioning into rupture simulations could change predictions of ground motion especially for faults with a history of repeated slip.'

Conclusion

The MIT laboratory program demonstrates that most of the mechanical energy released during seismic-like slip is converted to frictional heating near the fault, with only a modest fraction radiating as seismic waves and very little consumed by creating new surface area. Rapid, microsecond-scale heating can produce transient melting and generate glassy textures that mirror natural pseudotachylytes. While scaling to natural, kilometer-scale earthquakes requires careful treatment of additional complexities, these results provide essential physical constraints for rupture physics, fault zone evolution, and seismic-hazard modeling. Continued integration of laboratory thermometry, high-speed sensors, field observations, and numerical models will refine our ability to infer past fault behavior and to forecast aspects of future seismic risk.

Research note: The study was led by Matěj Peč and Daniel Ortega-Arroyo and reported in AGU Advances. Collaborators include Hoagy O’Ghaffari, Camilla Cattania, Zheng Gong, Roger Fu, Markus Ohl, and Oliver Plümper, representing MIT, Harvard University, and Utrecht University.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment