6 Minutes

The search for high-value minerals in space has often focused on asteroids, but new research suggests the Moon itself may be a richer and more accessible repository for platinum-group metals and water-bearing minerals. By analyzing impact-crater statistics and impact physics, researchers estimate that thousands of lunar craters could contain valuable deposits delivered by asteroid impacts. These findings reshape how we think about lunar resources and the near-term prospects for space mining and sustained human presence on the Moon.

Scientific background and context

Many asteroids fall into two broad compositional classes relevant to resource extraction: metallic (M-type) bodies rich in iron, nickel and platinum-group metals (PGMs), and carbonaceous (C-type) asteroids that are rich in hydrated minerals and volatiles. When such bodies strike the Moon, some material vaporizes, but under many conditions substantial fragments can survive and become trapped in the crater and its central uplift.

Impact craters larger than a few kilometers often develop a central peak where deep, excavated material is concentrated. That peak can also concentrate surviving portions of the impactor. Because the Moon has no atmosphere and limited geologic activity, impact-delivered material can remain accessible for eons in the regolith and within central peaks.

Methods and key findings

To estimate potential resource locations, the research team surveyed lunar craters by size and morphology, combining impact-model results with the known population and composition estimates of asteroids. They classified craters that could plausibly retain metallic or hydrated deposits after an impact. The study reports two headline estimates:

- Up to 6,500 craters larger than 1 kilometer may host platinum-group metals dispersed in the lunar regolith. Many of these occurrences will be low-concentration and widely mixed, but they represent a large statistical reservoir of PGMs.

- Up to 3,350 craters larger than 1 kilometer could contain hydrated minerals, an important source of water for in-situ resource utilization.

When the search is narrowed to the most promising geologic targets — craters larger than about 19 kilometers that have a well-defined central peak where surviving impactor material is most likely concentrated — the numbers fall to a more tractable set: roughly 38 candidate craters for concentrated PGM deposits and about 20 candidate craters for concentrated hydrated mineral deposits. These more focused targets are the most attractive initial exploration sites.

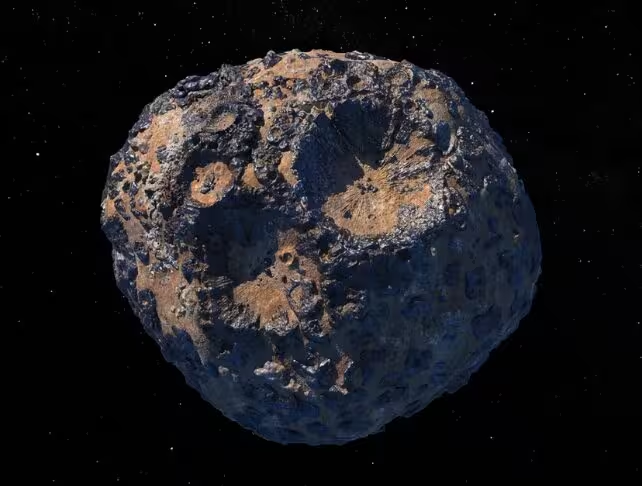

The 226-kilometer (140-mile) wide asteroid Psyche, which lies in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It's thought to be hugely rich in metal. (Peter Rubin/NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU)

How impacts can preserve metals and volatiles

Metals

Metallic asteroids can deliver dense metallic fragments that survive shock and heating during impact, particularly when incoming velocities and impact angles allow portions of the body to penetrate and be emplaced into the crater floor or central peak. Over geological time, micrometeorite gardening and space weathering mix these metals into the regolith, potentially making extraction more challenging but still feasible with appropriate processing.

Water and hydrated minerals

Carbonaceous impactors carry hydrated minerals and chemically bound water. Much of that water is lost to heat during high-energy impacts, but models and recent observations indicate that substantial fractions may survive, especially in larger, complex craters where ejecta bury and shield material, or where hydrated phases are chemically stabilized in cold traps or beneath the regolith.

Implications for lunar exploration and industry

If even a fraction of those estimated craters contain extractable PGMs or water, the Moon could become a hub for resource-driven activity. Water mined from hydrated minerals could be processed into drinking water, breathable oxygen, or rocket propellant (via electrolysis), dramatically lowering the cost and complexity of sustained lunar operations and deep-space missions.

Platinum-group metals have extensive industrial and medical applications on Earth and are rare in terrestrial ore bodies. A statistically large number of lunar sites hosting PGMs could make the Moon an attractive intermediate step before attempting the technically harder task of active asteroid capture or asteroid-surface mining.

However, accessibility is not the same as abundance per site. Many deposits are likely finely dispersed in the regolith, requiring new extraction and beneficiation technologies adapted to low-gravity, dusty environments. Regulatory, economic and planetary-protection frameworks will also influence whether and how these resources are exploited.

Detection strategies and technological needs

Remote sensing from lunar orbit is the most cost-effective first step for narrowing candidate craters. Techniques include visible and near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy, thermal mapping, synthetic-aperture radar to probe subsurface structure, and neutron or gamma-ray spectroscopy to detect elemental anomalies associated with metals or hydrogen-bearing compounds.

Targeted landers and rovers with in-situ analytical packages (X-ray fluorescence, mass spectrometers, drill cores) would follow orbital reconnaissance to confirm deposit grade and form. Developing rugged extraction systems that operate in lunar regolith and low gravity — such as heating and reduction for hydrated minerals or magnetic separation and molten metal processing for PGMs — will be essential.

Expert Insight

Dr. Laura Mendes, planetary geochemist (fictional), comments: "This study reframes the Moon as a statistically rich source of materials that were brought here by past impacts. The real advantage is logistical: lunar targets are far easier to reach and to monitor continuously than free-floating near-Earth asteroids. The challenge will be turning low-concentration, widely distributed metals into economic ore — but that is an engineering problem, not a fundamental barrier."

Conclusion

The Moon appears to offer a significantly larger number of potential targets for platinum-group metals and water-bearing minerals than previously recognized, at least in a statistical sense. Orbital remote sensing, followed by focused lander missions and development of extraction technologies, will determine how many of these candidate craters can become usable resource sites. For now, the possibility that thousands of lunar craters host extraterrestrial metals and hydrated minerals reframes the Moon as a practical stepping stone for resource-driven space exploration and a complement to asteroid-focused strategies.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment