4 Minutes

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) can begin long before painful joint swelling appears. New research shows that characteristic immune changes — detectable in blood years ahead of clinical synovitis — mark a silent stage in which autoimmune activity ramps up. Identifying these early biomarkers could improve prediction, enable earlier treatment and reduce the joint damage that defines RA.

Background: silent autoimmunity and ACPAs

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system attacks joint tissues, causing chronic inflammation, pain and progressive damage. Clinically obvious joint inflammation is termed synovitis. Before synovitis becomes apparent, some people already carry specific autoantibodies in their blood called anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs). While ACPA positivity increases RA risk, most ACPA-positive people do not immediately develop active disease, and the biological steps that lead from silent autoimmunity to clinical RA have been unclear.

Study design and methods

A US team led by researchers at the Allen Institute for Immunology, the University of California San Diego and the University of Colorado Anschutz followed a group of ACPA-positive individuals to map immune changes that precede RA. The cohort comprised 45 people deemed at risk because of ACPA in their blood; 16 subsequently developed clinical RA. Healthy control data provided comparison points. The investigators combined blood proteomics (measuring inflammatory proteins), cellular profiling of immune populations and functional analyses of B and T lymphocytes to build a timeline of immune activation during the at-risk stage.

Key discoveries

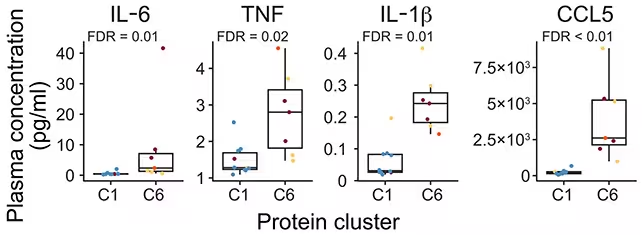

The study found a distinct rise in inflammatory proteins and immune activity in ACPA-positive participants relative to controls. In particular, proteins associated with innate and adaptive immune signaling were more abundant and active. Lymphocyte analysis showed that both B cells (the antibody-producing cells) and T cells (which help coordinate B cell responses) shifted toward a more 'primed' state. As individuals neared a diagnosis of RA, the frequency of T and B cells predisposed to inflammatory responses increased, including T cells that normally have less inflammatory phenotypes.

Inflammatory proteins were found to be more abundant in a group made up predominantly of people at risk of arthritis (C6). (He et al., Sci. Transl. Med., 2025)

There was overlap between those who did and did not progress to RA, but the emergent signature clarifies how the at-risk stage evolves biologically into clinical disease. The authors write that 'Our results support the concept that RA inflammatory disease begins well before the onset of active synovitis, earlier than clinically appreciated.'

Implications for diagnosis and treatment

Understanding which immune signals herald progression to RA opens multiple opportunities. First, panels of inflammatory proteins and immune-cell markers could refine risk stratification among ACPA-positive people, improving prediction beyond antibody status alone. Second, interventions timed to this preclinical window might prevent or delay synovitis and joint damage. The immunomodulatory drug abatacept, already used to delay RA in some high-risk patients, has evidence of reversing aspects of the immune activation highlighted here — supporting the idea that targeted therapies may be effective before full disease onset.

Kevin Deane, a rheumatologist at CU Anschutz, is quoted by the study team noting that the findings could 'support additional studies … to better predict who will get RA, identify potential biologic targets for preventing RA as well as identify ways to improve treatments.'

Conclusion

This research maps a preclinical phase of RA characterized by rising inflammatory proteins and increasingly activated B and T cells. While therapeutic changes based on these biomarkers will require further trials, the identification of measurable early signals moves the field toward proactive, preventive strategies that could limit the pain and disability of rheumatoid arthritis.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment