6 Minutes

New map of dark matter from distant star-forming galaxies

Rutgers University researchers have traced distinct large-scale patterns — described as "fingerprints" — in the distribution of dark matter by mapping the clustering of thousands of distant, young galaxies known as Lyman-alpha emitters. The results, published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, use the largest sample yet of these line-emitting galaxies to link how galaxies assemble with the unseen scaffolding of dark matter that shapes the cosmos.

By measuring where Lyman-alpha emitters cluster in space across different cosmic epochs, the team reconstructed regions where dark matter is densest and where future galaxies are likely to have formed. The analysis provides new, statistical constraints on the dark matter halos surrounding these galaxies and on the duration of the luminous Lyman-alpha phase.

Scientific background: Lyman-alpha emitters and dark matter halos

Lyman-alpha emitters (LAEs) are galaxies with strong emission in the Lyman-alpha transition of hydrogen. This ultraviolet emission appears prominently when galaxies are young and rapidly forming stars, or when neutral hydrogen in and around galaxies is illuminated. Because the Lyman-alpha line is bright and narrow, LAEs can be selected efficiently across large cosmological distances and used as tracers of structure in the early universe.

Dark matter itself does not radiate, but its gravity creates potential wells where gas condenses and galaxies grow. Observationally, astronomers infer dark matter by mapping how galaxies cluster: regions with stronger clustering correspond to more massive dark matter halos. The Rutgers-led team exploited this connection to estimate the typical halo masses that host LAEs and to visualize the dark matter overdensities where these galaxies reside.

Survey, datasets and methods

The project used deep narrowband imaging from the ODIN (One-hundred-square-degree DECam Imaging in Narrowbands) survey. ODIN is designed to detect large samples of Lyman-alpha emitters across wide sky areas using narrowband filters that isolate the Lyman-alpha line at specific redshifts. The Rutgers group concentrated on the COSMOS Deep Field, one of the most intensively observed regions of the sky, which enables robust foreground removal and cross-checks with multiwavelength data.

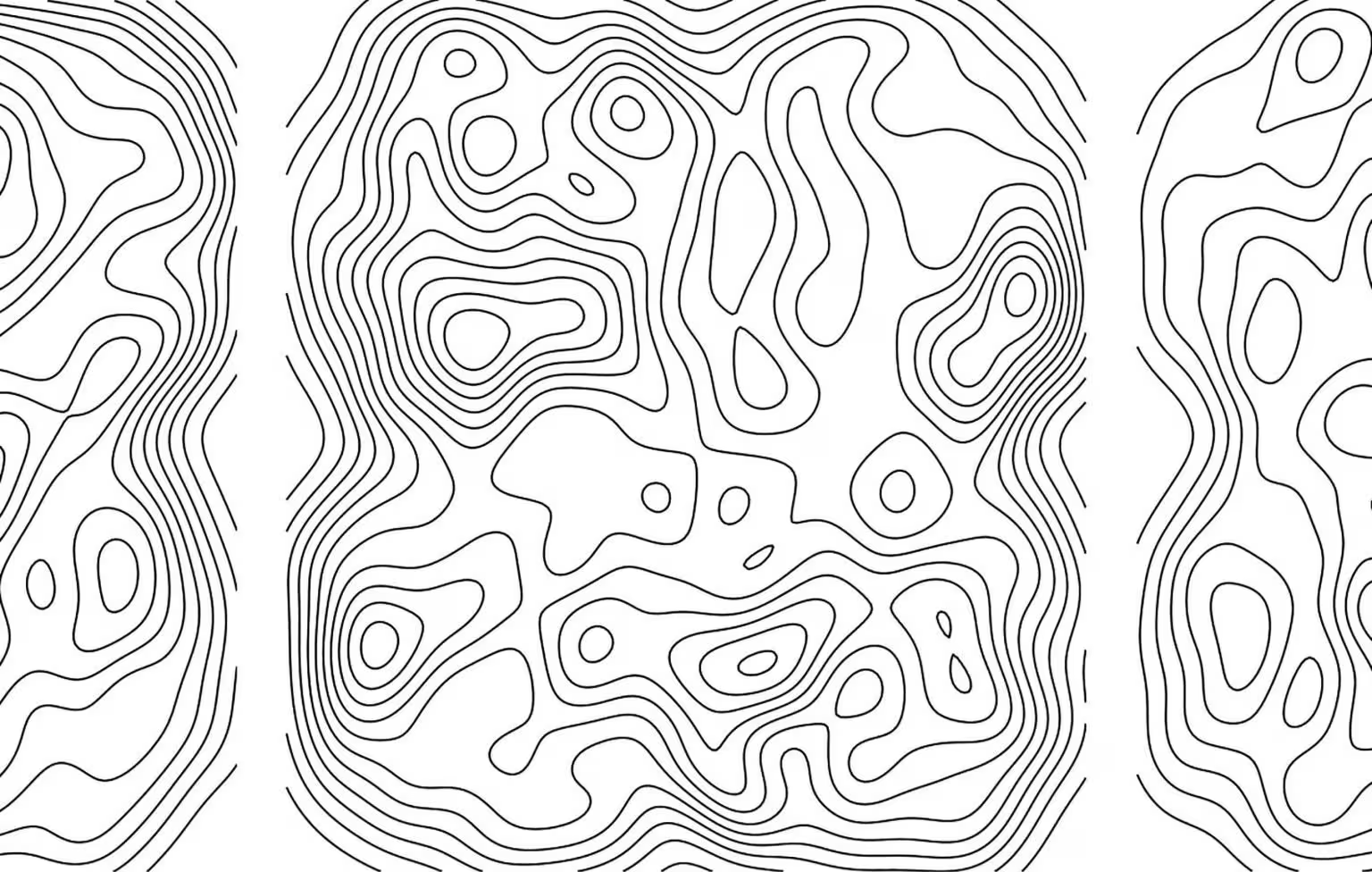

Schematic of the night sky areas are outlined with contour lines, similar to elevation lines on a hiking map, revealing the “fingerprints” of dark matter. Credit: Eric Gawiser, Dani Herrera/Rutgers University

The analysis covered three snapshots of cosmic time: roughly 2.8, 2.1 and 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang. For each epoch the team measured the angular correlation function — a standard statistical tool that counts galaxy pairs on the sky relative to random distributions — to quantify clustering strength. From that, they inferred the bias and typical masses of the underlying dark matter halos associated with LAEs.

Key findings and implications

The study produced two primary results with implications for galaxy evolution and the cosmic web:

- Fingerprints of dark matter. The clustering maps reveal contour-like structures where dark matter concentrates. Visualized like elevation lines on a hiking map, these contours show the locations of overdense regions that guide galaxy formation and mergers.

- Short-lived luminous phase. Only about 3% to 7% of the dense dark matter regions capable of hosting galaxies contain observable Lyman-alpha emitters at the times sampled. This low occupation fraction suggests the Lyman-alpha–bright phase is brief — lasting tens to hundreds of millions of years — relative to the lifetime of the host halo. In other words, LAEs are a transient but highly informative stage in galaxy build-up.

According to Eric Gawiser, Distinguished Professor in Rutgers’ Department of Physics and Astronomy and a co-author of the paper, the halo masses implied by the clustering results are consistent with a picture in which many LAEs evolve into present-day Milky Way–like galaxies. Dani Herrera, the lead doctoral researcher on the study, emphasized that tracking where dark matter is densest helps piece together the sequence of galaxy growth and merging driven by gravity.

Techniques that made this possible

The success of the analysis rests on three technical strengths: a very large LAE sample from narrowband imaging, the deep multiwavelength coverage of the COSMOS field to confirm selections and remove contaminants, and robust clustering statistics (angular correlation functions) that translate galaxy pair counts into halo mass estimates. As ODIN continues to expand its footprint, the sample size will grow and permit finer subdivisions by galaxy luminosity, environment and redshift.

Expert Insight

"These results show how statistical maps of faint galaxies can illuminate the invisible skeleton of the universe," says Dr. Lena Ortiz, a fictional but representative astrophysicist who studies galaxy formation. "Detecting the short duty cycle of Lyman-alpha emission tells us about episodic star formation and gas flows in early galaxies — a crucial piece for models that connect early starbursts to mature galaxies like the Milky Way."

"This kind of wide, uniform survey is exactly what we need to link models of dark matter halo growth with observational samples of growing galaxies," Ortiz adds.

Future prospects

As ODIN and complementary surveys accumulate more narrowband fields, astronomers will refine halo occupation fractions across cosmic history and test how environment influences galaxy properties such as star-formation rates, gas content and merging frequency. Combining these maps with spectroscopic follow-up and simulations will strengthen constraints on dark matter halo assembly and on the physical mechanisms that turn gas into stars.

Conclusion

By using Lyman-alpha emitters as beacons, the Rutgers-led team has produced one of the most comprehensive empirical pictures to date of where dark matter concentrates in the young universe. Their contour-style maps and clustering measurements reveal a fleeting but crucial phase in galaxy evolution and provide observational anchors for models of the cosmic web and halo growth. With larger ODIN samples and next-generation facilities, similar studies will further clarify how the invisible scaffolding of dark matter has shaped the galaxies we see today.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment