6 Minutes

Nightmares as a potential early warning of dementia

We spend roughly one-third of our lives asleep, and a substantial portion of that time is spent dreaming. Despite dreaming’s ubiquity, its relationship to long-term brain health remains incompletely understood. Recent longitudinal research suggests that recurrent bad dreams and nightmares in middle and older age may be an early indicator of increased risk for cognitive decline and dementia.

A 2022 longitudinal analysis published in The Lancet's eClinicalMedicine examined whether self-reported nightmare frequency predicts future brain health outcomes. The work draws attention to nightmares—not just insomnia or sleep duration—as a measurable sleep symptom that could flag future neurodegenerative risk.

How the study was done and key findings

The analysis pooled data from three large U.S. aging cohorts. Participants were dementia-free at baseline and completed questionnaires between 2002 and 2012 that included items about how often they experienced bad dreams or nightmares (defined in the survey as bad dreams that cause awakening).

- Sample sizes and follow-up: the analysis included more than 600 middle-aged adults (35–64 years old) and about 2,600 older adults (79+). Middle-aged participants were followed for an average of nine years; older participants were followed for an average of five years.

- Outcome measures: investigators tracked cognitive decline (a rapid deterioration in memory and thinking skills) and incident dementia diagnoses during follow-up.

The central result was that frequent nightmares were associated with substantially higher later risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Middle-aged adults reporting weekly nightmares were about four times more likely to develop cognitive decline over the subsequent decade. Among older adults, weekly nightmares were associated with roughly double the risk of a later dementia diagnosis.

A striking sex difference emerged: the association was far stronger in men than in women. Older men who experienced weekly nightmares had approximately a fivefold increase in dementia risk compared with men reporting no bad dreams; for women the increase was about 41 percent. A similar pattern appeared in the middle-aged group. These effect sizes suggest nightmares could be one of the earliest clinical signals of a neurodegenerative process—sometimes preceding memory or thinking problems by years or even decades.

Possible interpretations and biological context

Two broad explanations could account for the association. First, frequent nightmares may themselves reflect underlying brain changes that later manifest as dementia (that is, nightmares are an early symptom). Second, nightmares could contribute causally to processes that promote neurodegeneration—for example, by disrupting restorative sleep or increasing stress and inflammation.

At present the evidence favors the former interpretation (nightmares as an early marker), but observational design prevents definitive causal inference. Importantly, the study controlled for many common confounders but cannot exclude all sources of bias.

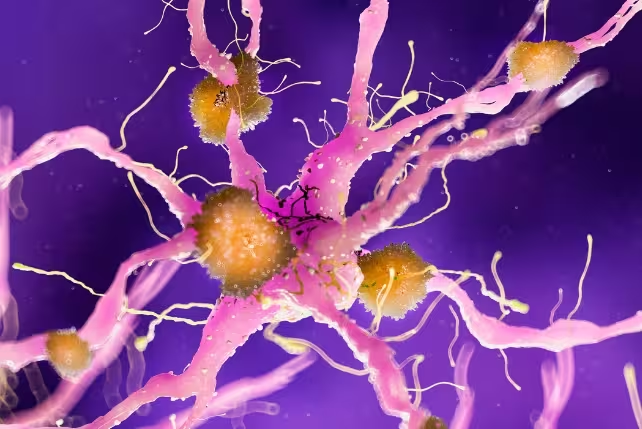

From a neuropathological perspective, neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s are linked to abnormal protein accumulations in the brain—most notably amyloid-beta and tau. Preclinical studies show that sleep quality affects the brain’s clearance of metabolic waste, including amyloid proteins; fragmented or disturbed sleep may therefore influence pathological protein buildup over time.

Nightmares, REM sleep and brain clearance

Nightmares typically occur during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, a phase associated with vivid dreaming. REM disruptions and repeated nocturnal awakenings may impair the glymphatic system, a brain-wide clearance mechanism active during sleep. If repeated nightmares chronically fragment REM and deeper sleep stages, they could plausibly accelerate pathological changes linked to dementia—though this remains to be proven in human trials.

Treatment implications and future research directions

There is a practical upside: recurring nightmares are treatable. Behavioral therapies (for example, imagery rehearsal therapy) and several pharmacologic options are established first-line treatments for frequent nightmares. Intriguingly, some studies have reported that treating nightmares can reduce markers tied to Alzheimer’s pathology in animal models and that case reports note cognitive improvements after successful nightmare interventions in humans.

If nightmares are an early marker, routine screening in midlife could identify people at elevated risk for closer cognitive monitoring or prevention trials. If nightmares contribute causally, treating them might slow pathological progression and delay or prevent dementia in some individuals. Both possibilities motivate randomized clinical trials that evaluate whether nightmare treatment alters biomarker trajectories (amyloid and tau measures), cognitive decline rates, or clinical dementia incidence.

Planned research steps include studying younger populations to determine whether nightmares decades before old age carry predictive value, and examining other dream characteristics—such as dream vividness and recall frequency—to see if they refine risk prediction.

Expert Insight

"Nightmares are a window into sleep architecture and emotional processing. When they become frequent in midlife, we shouldn’t dismiss them as benign oddities. They may reflect subtle changes in brain networks that are vulnerable to neurodegeneration," says Dr. Emily Hartman, a clinical neuroscientist and sleep researcher. "Prospective trials that combine sleep-focused therapies with biomarker monitoring could tell us whether addressing nightmares modifies the course toward dementia."

Conclusion

Frequent nightmares in middle and older age appear to be associated with an elevated risk of later cognitive decline and dementia, with particularly strong associations observed in men. While causality remains uncertain, nightmares are a measurable, treatable symptom. That makes them a promising candidate for early screening and an actionable target for intervention studies aiming to preserve brain health.

Further longitudinal and interventional research—combining sleep assessment, neuroimaging, and molecular biomarkers—is needed to clarify whether nightmare treatment can reduce dementia risk and to understand the underlying mechanisms linking disturbed dreaming to neurodegeneration.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment