6 Minutes

A tiny fossil with big implications

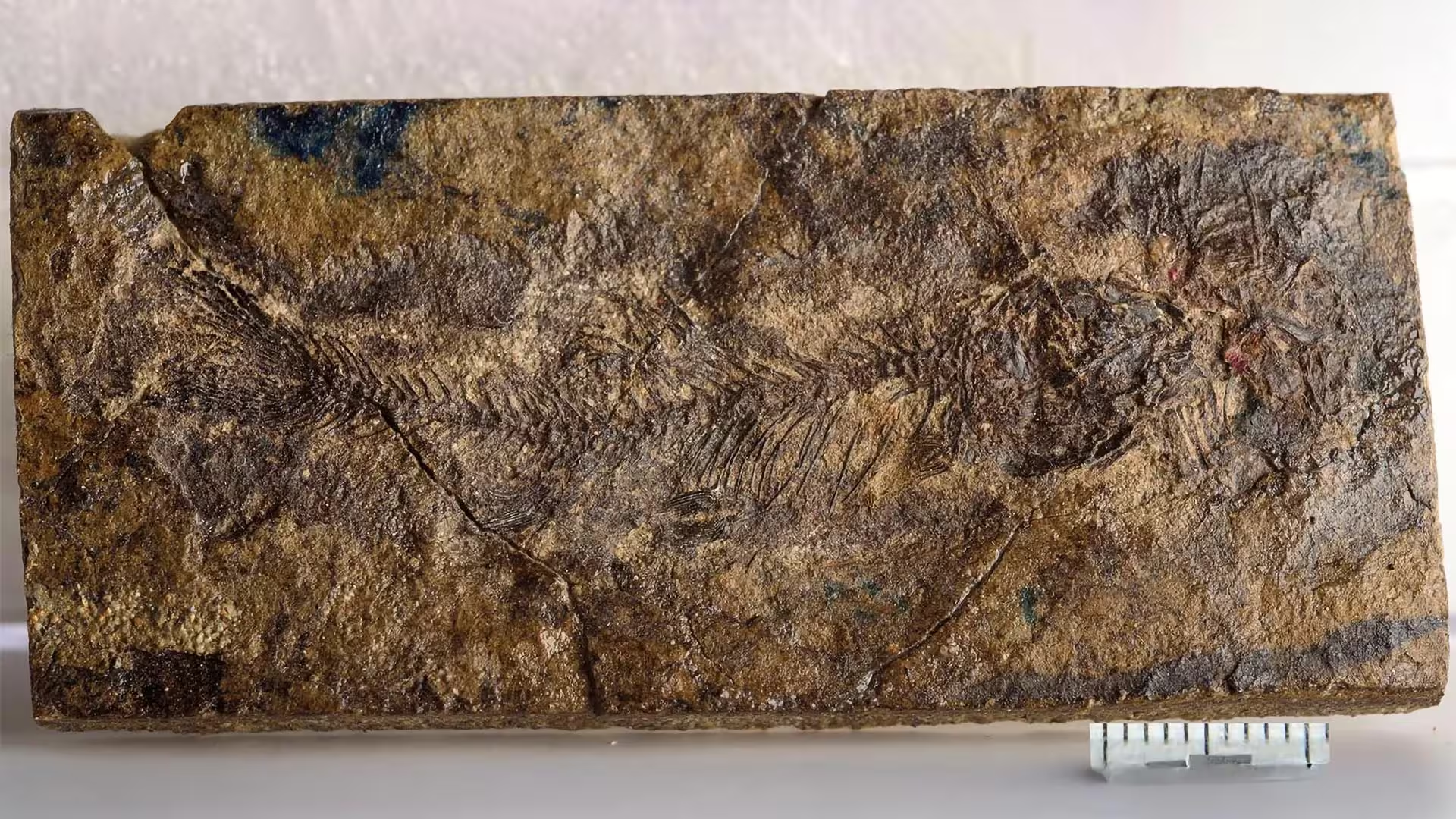

A palm‑sized fish fossil discovered in southwestern Alberta is forcing scientists to rethink the early evolution and biogeography of otophysans — the supergroup that includes catfish, carps and tetras and today makes up roughly two‑thirds of all freshwater fish diversity. The specimen, a roughly 4 cm long skeleton from the Late Cretaceous (the same broad era as Tyrannosaurus rex), has been described as a new species: Acronichthys maccognoi. The study detailing the find was published in Science on October 2, 2025, and the fossil was analyzed by researchers from Western University, the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology and collaborators at institutions in Canada and the United States.

This fossil is significant because it preserves anatomical features linked to the unique otophysan hearing system. Otophysans possess a modified chain of the first few vertebrae and associated bones — commonly referred to as the Weberian apparatus — that transmit swim‑bladder vibrations directly to the inner ear. That adaptation dramatically improves sensitivity to sound and is a defining trait of the group; it is visible in the new fossil, and micro‑CT imaging confirmed the fine internal structure.

Imaging, methods and why micro‑CT matters

Researchers combined traditional paleontological preparation with advanced imaging. Lisa Van Loon used synchrotron beamlines at the Canadian Light Source (Saskatoon) and the Advanced Photon Source (Lemont, Illinois) to acquire high‑resolution micro‑CT scans. Micro‑CT is a non‑destructive X‑ray tomography method that produces three‑dimensional virtual models by rotating the specimen and compiling hundreds to thousands of 2‑D projections.

What micro‑CT revealed

- Fine skeletal details: The scans clarified vertebral modification patterns and tiny bones linking the swim bladder area to the ear region.

- Internal preservation: The method exposed internal anatomical relationships that are impossible to observe on the surface of fragile matrix‑enclosed fossils.

Van Loon explained the practical importance: micro‑CT scanning “provides not only the best method for acquiring detailed images of what's inside, they're also the safest way to avoid destroying the fossil all together.” The non‑invasive approach allowed the team to document structures diagnostic of early otophysan anatomy without destructive preparation.

Key discoveries and evolutionary implications

Acronichthys maccognoi fills a notable gap in the fossil record of otophysans by representing the oldest known member of the group from North America. Neil Banerjee, an Earth sciences professor and study co‑author, said: “The reason Acronichthys is so exciting is that it fills a gap in our record of the otophysans supergroup. It is the oldest North America member of the group and provides incredible data to help document the origin and early evolution of so many freshwater fish living today.”

Using morphological data and molecular clock calibrations, the authors estimate that the marine‑to‑freshwater shift within otophysans occurred around 154 million years ago (Late Jurassic), after the early stages of Pangea’s breakup. Crucially, the new analyses suggest that the colonization of freshwater habitats by otophysan lineages happened more than once, implying multiple independent invasions from marine ancestors into rivers and lakes.

This result raises biogeographic questions: how did ancestral otophysans disperse to populate freshwater habitats on multiple continents if their early range included saltwater environments and continents were separating? The fossil was found well inland from the Western Interior Seaway, showing freshwater forms were present in continental settings by the Late Cretaceous. Possible explanations include dispersal through ephemeral coastal corridors, freshwater plume rafting, or repeated, localized invasions from marine shorelines — but the fossil record remains sparse and more data are needed.

Context and scientific background

Otophysans are ecologically dominant in modern freshwaters: groups such as Cypriniformes (carps, minnows), Siluriformes (catfishes) and Characiformes (tetras) are globally important in rivers and lakes. The Weberian apparatus is one of the key evolutionary innovations that may have facilitated their success by enhancing acoustic sensitivity and intraspecific communication in complex freshwater environments.

The new Acronichthys fossil comes from a period when Earth’s ecosystems were changing rapidly. The Late Cretaceous saw extensive inland seas and evolving continental coastlines; documenting freshwater vertebrates from these intervals helps reconstruct how modern freshwater faunas assembled across deep time.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maria Santos, a paleoichthyologist not involved with the study, commented: “Finding a well‑preserved otophysan from the Late Cretaceous in Alberta is like discovering a missing chapter in a book about freshwater evolution. The micro‑CT data are especially valuable because they allow comparisons with living taxa at a level of detail that conventional methods can’t match. This specimen supports the idea that otophysan traits evolved early and were repeatedly co‑opted during transitions from marine to freshwater habitats.”

Conclusion

Acronichthys maccognoi is a small fossil with outsized implications. By documenting an early North American otophysan with clear modifications linked to the Weberian apparatus, the discovery refines divergence timing estimates and supports multiple, independent marine‑to‑freshwater transitions within the group. The find underscores the value of modern imaging methods and of fossil localities in regions like Alberta for solving long‑standing questions about the assembly and global spread of freshwater biodiversity. Continued fieldwork and high‑resolution imaging will be essential to map the full story of how otophysans came to dominate rivers and lakes worldwide.

Source: University of Western Ontario. Published October 5, 2025. Study published in Science on October 2, 2025. Institutions involved include Western University, the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Alberta.

Source: sciencedaily

Leave a Comment