4 Minutes

Discovery: a window into a 112-million-year-old forest

New amber deposits uncovered in a quarry in Ecuador have preserved insects and plant remains dated to roughly 112 million years ago, offering a rare snapshot of a Cretaceous forest that once stood on the southern supercontinent Gondwana.

Researchers who analyzed the Genoveva quarry material report the specimens in Communications Earth & Environment. The amber comes from the Hollín Formation, a sedimentary unit within Ecuador's Oriente Basin. The fossils capture a moment in time from the mid-Cretaceous and provide direct evidence of organisms and ecological interactions that are otherwise poorly represented in the Southern Hemisphere fossil record.

Site, materials and preserved inclusions

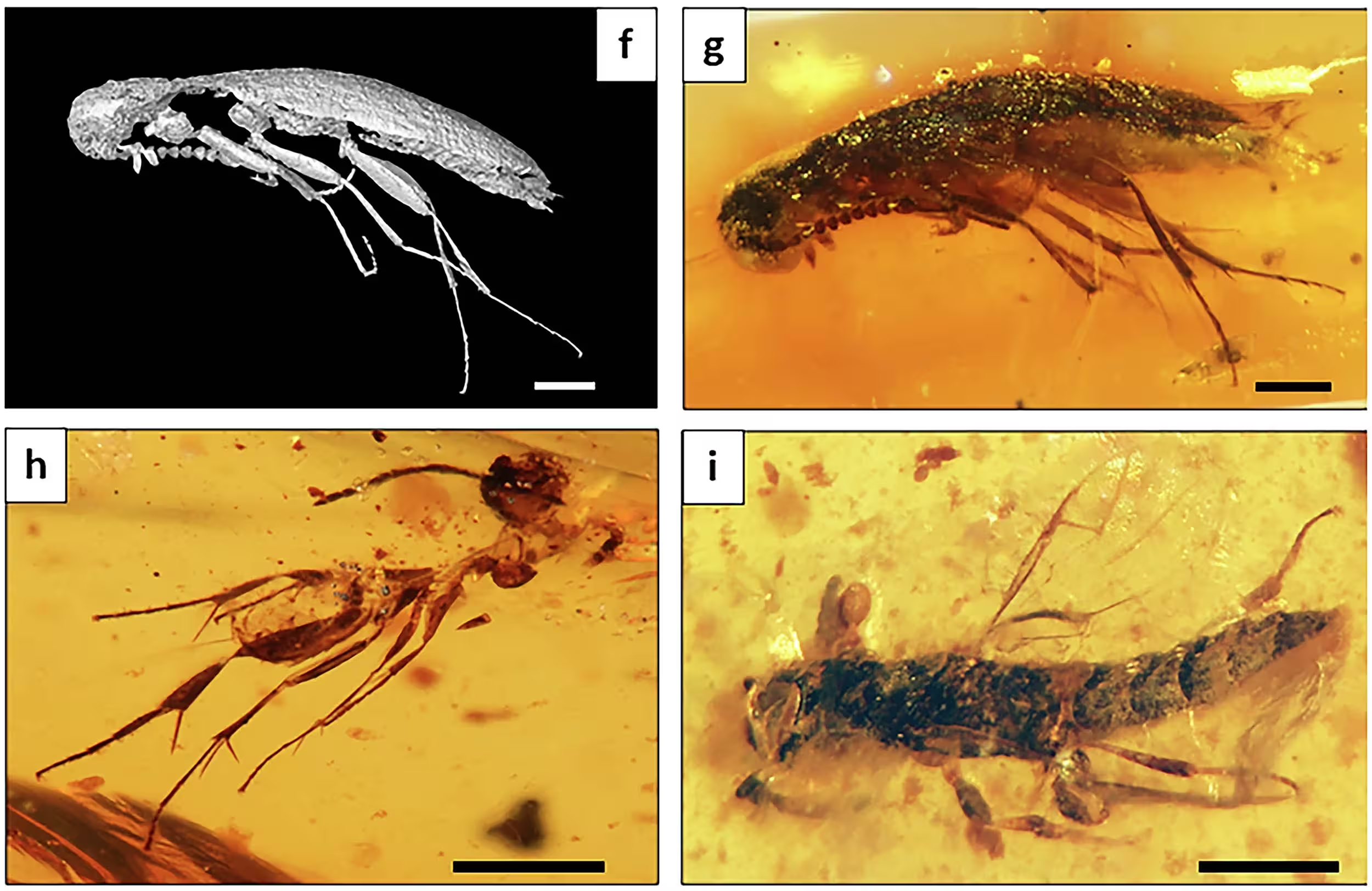

Field teams collected both amber and the surrounding matrix, identifying two main types of resin-derived material: subterranean amber formed around plant roots and aerial amber produced when resin was exposed to air. In 60 aerial amber samples the authors identified 21 bio-inclusions, including insects from at least five orders. Documented groups include Diptera (true flies), Coleoptera (beetles) and Hymenoptera (ants, wasps and relatives), as well as a fragment of spider web preserved in the resin. Microfossils and plant remains recovered from the rock—spores, pollen and other organic fragments—help reconstruct the local vegetation.

The combination of insect inclusions and plant microfossils indicates a humid, densely vegetated forest dominated by resin-producing trees. The presence of different amber types also suggests a landscape where resin production occurred at multiple levels of the forest, from canopy drips to root-associated secretions.

Scientific context and implications

Amber records extend back more than 300 million years, but most major, well-studied deposits have been discovered in the Northern Hemisphere. That geographic bias has limited our understanding of Cretaceous biodiversity and ecosystem dynamics across Gondwana as continents fragmented.

The Ecuador find helps fill that gap. Preserved bio-inclusions allow direct study of insect morphology and ecology, while associated pollen and spores provide data on plant composition and climate. Together these lines of evidence improve reconstructions of palaeoecology, trophic networks and habitat structure for southern Cretaceous forests.

Lead author Xavier Delclòs commented on the discovery: "This deposit opens a rare window onto the southern Cretaceous. The combination of insects and plant microfossils will let us test hypotheses about how Gondwanan ecosystems functioned and how they differed from northern contemporaries." The research team emphasizes that the deposit is a significant resource for future work on Cretaceous biodiversity in South America.

Research methods and next steps

Analytical techniques included careful mechanical preparation of amber, microscopic imaging of inclusions, and palynological study of accompanying sediments. Radiometric and stratigraphic constraints placed the age at about 112 million years. Future work will expand sampling across the Hollín Formation, apply advanced imaging (e.g., micro-CT) to reveal fine anatomical detail inside inclusions, and compare Ecuadorian assemblages with northern hemisphere amber faunas to track biogeographic patterns.

Conclusion

The Ecuadorian amber discovery provides a rare, direct look at life in southern Gondwana during the mid-Cretaceous. By preserving insects, web material and plant microfossils, the deposit offers multiple lines of evidence to reconstruct ancient forest ecosystems, filling a critical geographic gap in the amber record and opening new avenues for palaeobiological and biogeographic research.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment