4 Minutes

Rethinking Alzheimer’s: an immune misfire in the brain

Alzheimer's disease may be better understood not only as a proteinopathy but also as a disorder driven by the brain's own immune response. In this emerging view, immune cells in the brain mistake neuronal components for foreign invaders, launching a sustained defensive reaction that gradually impairs neuron function and leads to cognitive decline. Over time this chronic immune activity produces progressive loss of memory, reasoning, and daily function — the hallmarks of dementia.

Key to this perspective is the dual role of beta-amyloid. Long studied as the core component of amyloid plaques, beta-amyloid may have an antimicrobial or immune-supporting function: it helps neutralize microbes and bolster innate defenses. Unfortunately, when beta-amyloid accumulates or becomes dysregulated, it can amplify immune activation and sustain a self-directed attack on brain tissue. This autoimmune-like process could explain why classic systemic immunosuppressive therapies, such as corticosteroids effective in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, have limited benefit in Alzheimer’s — the brain’s immune environment and the agents that regulate it are unique.

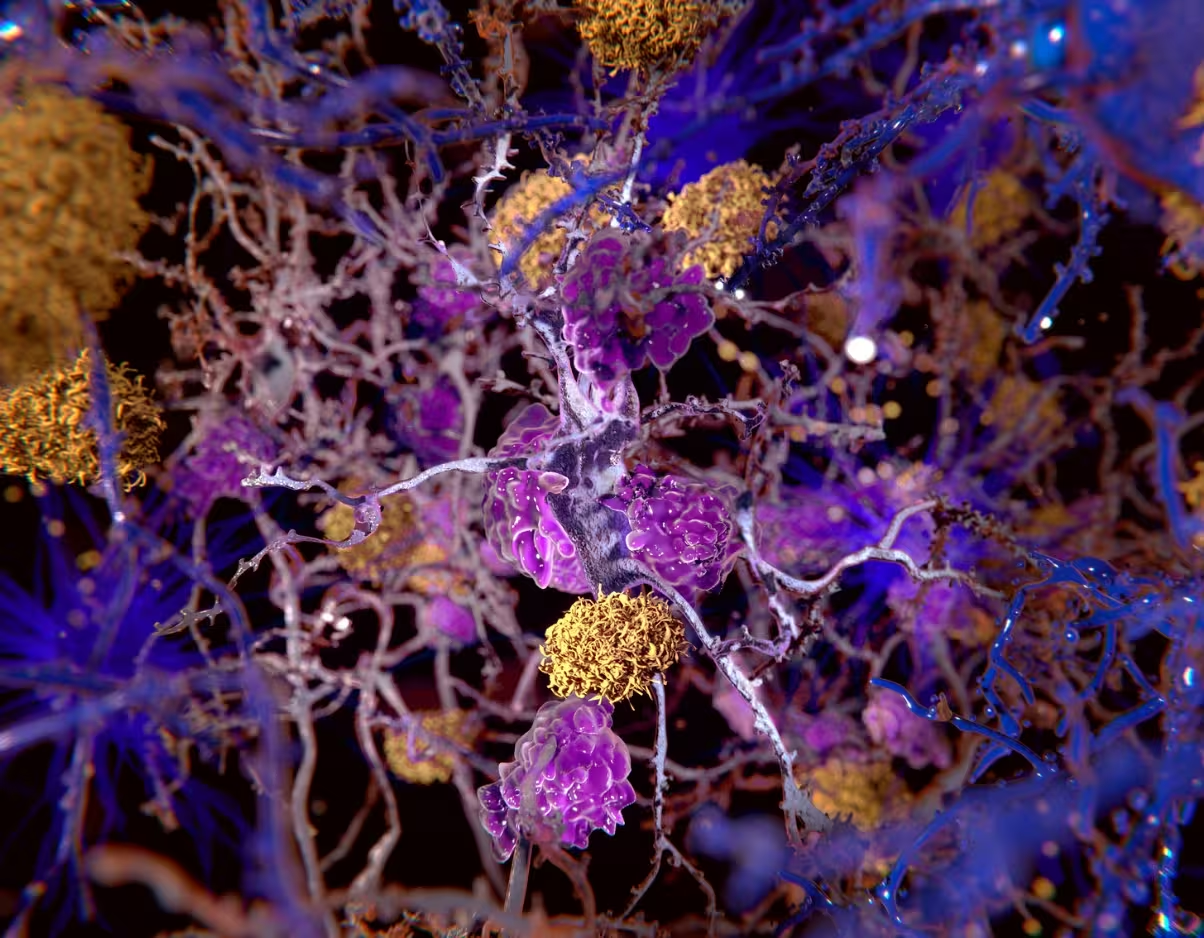

Illustration of beta-amyloid plaques (yellow) amongst neurons.

Scientific background and alternative hypotheses

Modern research is expanding beyond a single explanation for Alzheimer’s. Several competing and complementary theories exist:

- Mitochondrial dysfunction: Mitochondria are cellular powerhouses that convert oxygen and glucose into usable energy. If mitochondrial function falters in neurons, the resulting energy shortfall undermines memory and cognitive processing, contributing to neurodegeneration.

- Chronic infection: Some investigators propose that recurrent or persistent infections — including oral bacteria migrating to the brain — could trigger inflammatory cascades that culminate in dementia.

- Metal imbalance: Abnormal handling of essential metals such as zinc, copper, or iron may disrupt neuronal biochemistry and promote aggregation of toxic proteins.

These theories are not mutually exclusive. For example, an infection could stimulate beta-amyloid production as a protective response, which then spirals into harmful inflammation in vulnerable individuals.

Implications for treatment and research

If Alzheimer’s involves immune misdirection within the central nervous system, therapeutic strategies must target brain-specific immune pathways. Promising directions include modulation of microglia (the brain’s resident immune cells), targeted anti-inflammatory agents that cross the blood-brain barrier, and approaches that restore healthy beta-amyloid dynamics without eliminating its protective roles. Biomarkers that distinguish antimicrobial responses from pathological autoimmunity will be critical to guide precision therapies.

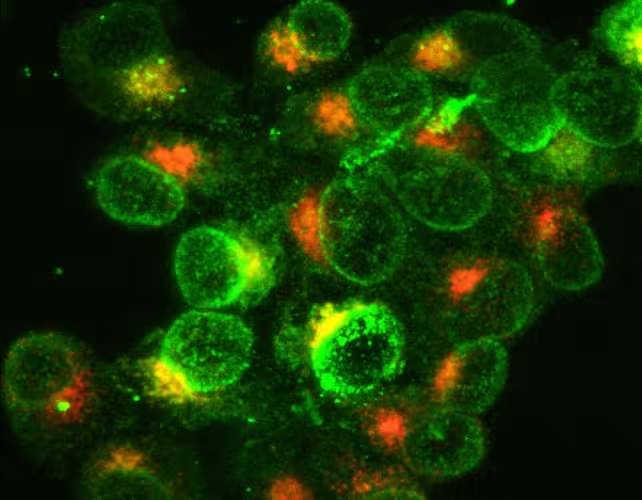

White blood cells of the immune system, activated to fight a bacterial infection. Green shows expression of molecules on their surfaces, and orange shows synthesis of molecules inside the cells.

The public-health scale is enormous: dementia affects over 50 million people worldwide, with a new diagnosis every few seconds. Beyond the human cost to patients and families, the economic burden on healthcare systems demands innovative, mechanistically informed solutions.

Research priorities and future prospects

Progress will require interdisciplinary work linking neurology, immunology, infectious disease, and bioinorganic chemistry. Large-scale longitudinal studies, improved brain-penetrant imaging agents, and therapeutic trials that specifically manipulate neuroimmune signaling are top priorities. Whether Alzheimer’s ultimately proves to be primarily autoimmune, infectious, metabolic, or a combination, reframing the disease around immune regulation opens new paths for diagnostics and treatments.

Conclusion

Viewing Alzheimer’s through an immune-centered lens reframes long-held assumptions and highlights novel targets for intervention. Continued research into how beta-amyloid, microglia, mitochondria, pathogens, and metals interact in the aging brain will be essential to prevent and treat this global health crisis.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment