6 Minutes

Fungal hydrogels as a biomaterial opportunity

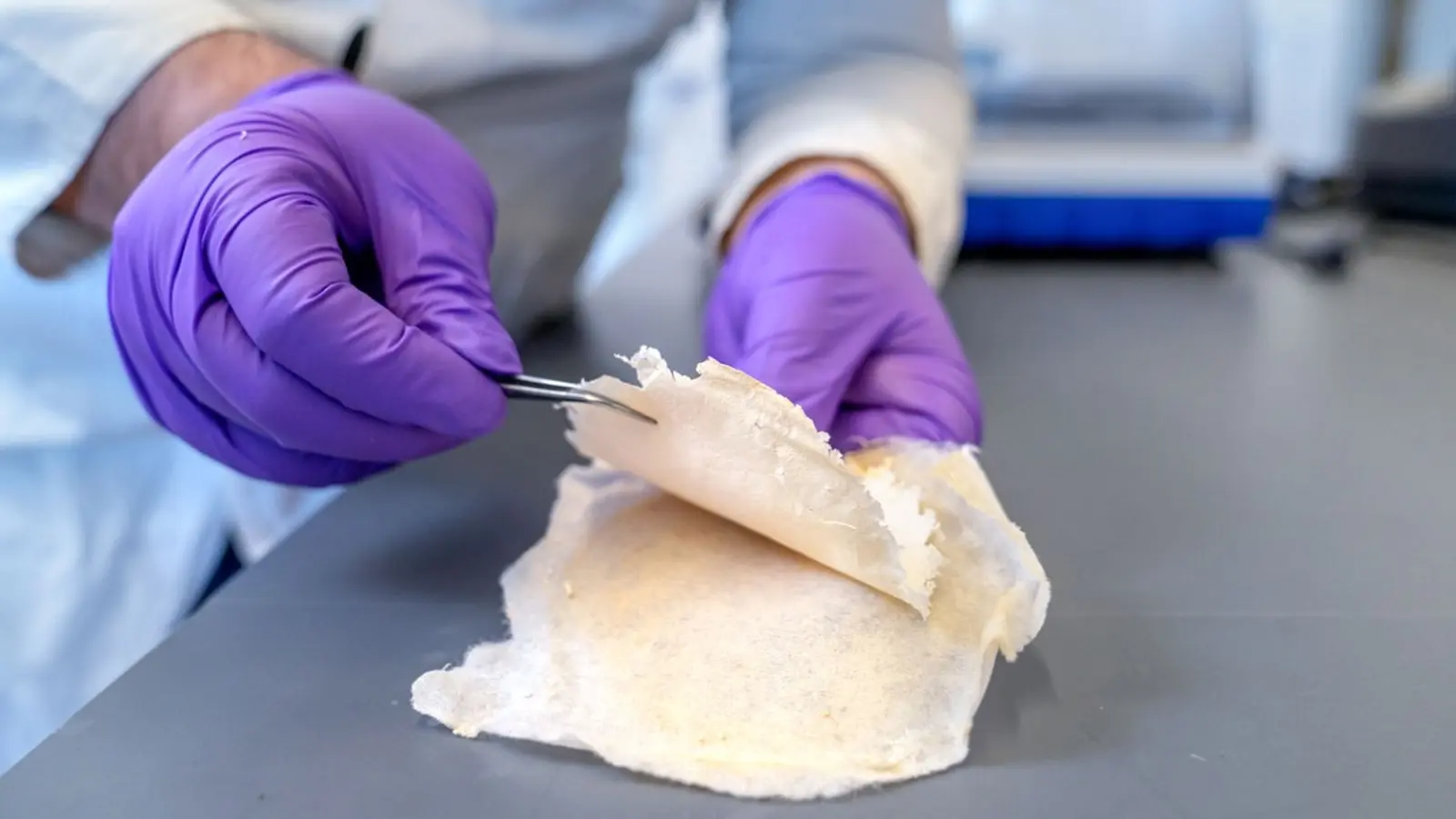

Researchers are exploring an unexpected source for next-generation wound dressings: living fungal networks. A soil mold called Marquandomyces marquandii has shown the ability to form robust, water-retaining hydrogels with layered, porous microstructures that resemble aspects of human soft tissue. These fungal-derived hydrogels could eventually serve as biocompatible scaffolds for tissue repair, cell culture, wearable bioelectronics, or even mineralized bone templates.

Biology and materials science meet: what is mycelium-driven hydrogel?

Most people recognize fungi by mushrooms or fuzzy mold, but the bulk of a fungus is an interwoven network of filaments called mycelium. Mycelium is composed largely of chitin, a structural polysaccharide also found in insect exoskeletons and shellfish. Because mycelial networks grow as long, branching filaments that form cross-linked layers, materials scientists see potential to exploit that architecture as a living hydrogel.

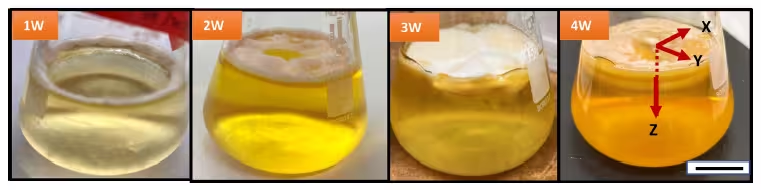

At the University of Utah, engineers used stationary liquid fermentation to cultivate M. marquandii and observed a striking outcome: colonies that formed thick, multilayered mycelial sheets capable of holding high water content. Under these submerged growth conditions the fungus created alternating bands of different porosity, producing a composite material with both spongy and denser regions—features that are valuable for mimicking the viscoelastic and transport properties of skin and other soft tissues.

Experiment details and key material properties

When grown in stationary liquid culture, M. marquandii produced a hydrogel-like mycelial matrix capable of retaining up to 83 percent water by volume. Microscopy and porosity analysis indicated a layered structure: surface layers with roughly 40 percent porosity, alternating with internal bands showing about 90 percent and 70 percent porosity. The researchers attribute this pattern to changes in fungal growth strategy—surface-adjacent filaments prioritize lateral expansion and form denser layers, while submerged regions grow more filamentously and generate highly porous bands.

Weekly progression of M. marquandii growth on potato dextrose broth under stationary liquid fermentation over 4 weeks. (Agrawal et al., JOM, 2025)

Those differing porosities matter for biomedical design. Denser layers can provide structural integrity and slower mass transfer, while high-porosity bands can host cells, nutrients, or fluids and support rapid diffusion. The team also observed that modifying culture conditions—oxygen availability, temperature, nutrient concentration—can tune the hydrogel microstructure and therefore its mechanical and transport behavior.

Potential biomedical applications

Bio-integrated hydrogels aim to replicate the multilayered, viscoelastic properties of skin, cartilage, and other tissues. Because mycelium is biocompatible and inherently porous, M. marquandii hydrogels could serve as:

- Wound dressings that maintain a moist healing environment and provide structural support.

- Scaffolds for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, where cells are seeded into mycelial matrices.

- Templates for mineralization to produce bone-like scaffolds.

- Materials for wearable bioelectronic devices or cell bioreactors that require soft, hydrated interfaces.

University of Utah materials engineer Steven Naleway noted that the ‘‘big, beefy mycelial layers’’ produced by M. marquandii are primarily chitinous, offering a combination of sponginess and biocompatibility that is attractive for these uses.

Safety, limitations and research priorities

Translating a living fungal material into clinical use will require rigorous safety testing. M. marquandii is not known to be a human pathogen, but chitin and fungal components can cause allergic reactions in some individuals. Animal studies and immunological assays are necessary to understand allergic or inflammatory potential. Long-term stability, sterility, and control of growth are additional hurdles: any living dressing must be safe, controllable, and compatible with existing medical sterilization and regulatory frameworks.

Researchers emphasize the need to demonstrate how fungal hydrogels interact with human cells and tissues, to optimize growth protocols so that desired properties are reproducible, and to design containment strategies that eliminate risks of uncontrolled fungal proliferation—essential steps before any clinical application.

Related technologies and future prospects

Fungal mycelium is already studied in sustainable materials science—for example, as packaging, insulation, and composite panels—because it offers a renewable, low-energy route to structured biomaterials. The move toward living fungal hydrogels extends this agenda into biomedicine. Integrating mycelial growth with techniques such as mineralization, 3D bioprinting, or biochemical functionalization could enable hybrid scaffolds tailored for specific tissues.

Beyond clinical applications, mycelium hydrogels could also support in vitro research: cell culture scaffolds and bioreactors that mimic tissue mechanics and transport while remaining more sustainable than synthetic polymers.

Expert Insight

Dr. Lina Ortega, a biomedical engineer specializing in biomaterials, commented: "The most exciting aspect of mycelium-based hydrogels is their intrinsic hierarchical structure. If we can reliably tune porosity and biochemical surface properties, these materials could provide a low-cost, scalable alternative to synthetic scaffolds for a range of regenerative applications. The challenge will be demonstrating reproducible safety and performance in vivo."

Conclusion

Marquandomyces marquandii demonstrates that some fungi can produce living, multilayered hydrogels with high water content and tunable porosity—properties relevant to wound healing and tissue engineering. While the path to clinical use is long and will require extensive safety, immunological, and regulatory work, fungal hydrogels represent a promising intersection of microbiology and materials science. Continued research into controlled growth, functionalization, and biocompatibility could make mycelium-derived materials an important addition to the future biomaterials toolkit.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment