5 Minutes

New findings and the original image caption

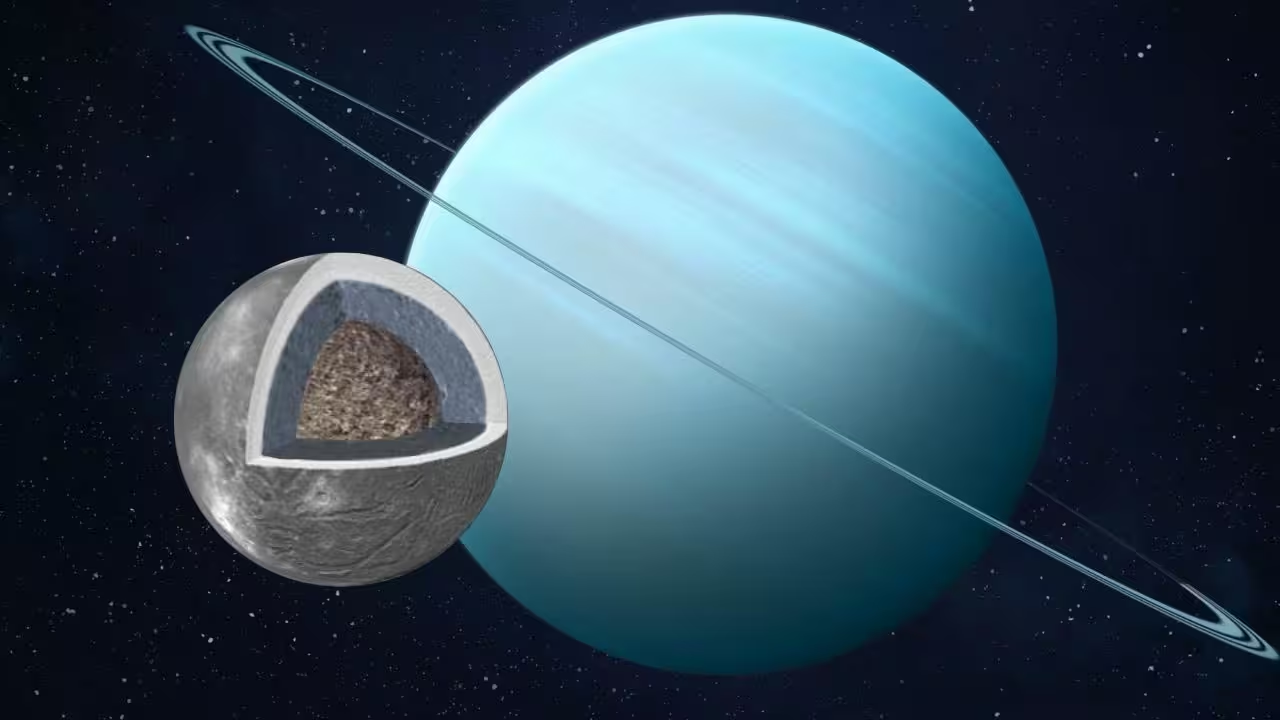

New research suggests that Ariel, a moon of Uranus, might have once harbored an ocean about 100 miles (170km) deep.

A recent study published in Icarus presents growing evidence that Ariel—a mid-sized, icy moon of Uranus—could have supported a vast subsurface ocean early in its history. Researchers combined surface mapping with tidal-stress modelling to infer that a liquid layer beneath Ariel’s ice shell may once have been hundreds of kilometers thick, far exceeding the average depth of Earth's oceans.

Surface clues: fractures, grabens and cryovolcanic plains

Ariel, about 720 miles (1,159 km) across, displays a striking dichotomy of terrains: heavily cratered regions alongside smooth plains thought to originate from cryovolcanism (volcanic activity involving water, ammonia or other volatiles rather than molten rock). Large-scale fractures, ridges, and grabens—blocks of crust that have dropped relative to surrounding material—dot the surface and point to intense tectonic stresses in the moon’s past.

Caleb Strom (first author) and co-author Alex Patthoff (Planetary Science Institute) reasoned that such global-scale deformation requires a mobile interior. By mapping surface structures and comparing them to computer models of tidal deformation, the team constrained Ariel’s past orbital and internal conditions that could produce the observed stress patterns.

Tidal heating, orbital eccentricity and ocean depth

Tidal stress arises when a moon’s shape changes during its orbit: gravitational pull from the host planet stretches and squashes the satellite, generating heat and mechanical stress. The study indicates Ariel once had an orbital eccentricity near 0.04—about 40 times its present value. Although modest by absolute terms, this eccentricity would have amplified tidal flexing enough to fracture the crust if a subsurface ocean existed beneath a relatively thin ice shell or if a deeper ocean combined with moderate eccentricity produced the same effect.

At the peak of tidal activity, models show Ariel’s interior could have supported an ocean exceeding 100 miles (170 km) in depth. For perspective, Earth’s Pacific Ocean averages roughly 2.5 miles (4 km) deep—making Ariel’s hypothetical ocean orders of magnitude deeper by vertical extent within the satellite’s layered interior.

The study explains that to create the scale of fractures observed today, either the ice lid must have been thin atop a large ocean, or Ariel must have experienced higher eccentricity with a somewhat smaller ocean. In both scenarios, a liquid layer is essential to decouple the crust from the deeper solid interior and allow the mechanical response required to form grabens and ridges.

Context within the Uranian system

This Ariel paper follows a similar analysis of Miranda by the same team, supporting the idea that multiple Uranian moons may have hosted subsurface oceans—a configuration sometimes described as "twin ocean worlds." Co-author Tom Nordheim (Johns Hopkins APL) notes that researchers have only imaged the southern hemispheres of Ariel and Miranda at high resolution. Their modelling predicts where fractures and ridges should appear on the unmapped northern hemispheres, guiding future mission planning.

If confirmed, ocean-bearing moons in the Uranus system would add to the growing list of potentially habitable or chemically active icy worlds in the outer Solar System and refine our understanding of how tidal heating sculpts satellite geology.

Mission implications and future observations

Direct confirmation of a present or past ocean beneath Ariel requires new spacecraft data. Key instruments for an orbiter or flyby would include:

- Ice-penetrating radar to probe layered structure and detect liquid pockets.

- Magnetometers to search for induced magnetic fields produced by conductive subsurface oceans.

- High-resolution imaging and topography (stereo cameras, laser altimeter) to map tectonic features across currently unseen hemispheres.

- Gravity science to constrain interior mass distributions and differentiate between a solid interior and a liquid layer.

A dedicated Uranus system mission—an orbiter with a suite of geophysical instruments—would be the most effective path to test the modelling results and to survey Ariel, Miranda, and other moons for signs of past or present liquid layers.

Expert Insight

"Ariel’s surface tells a story of internal dynamism that we are only beginning to decode," says Dr. Elena Morales, planetary geophysicist at the University of Arizona. "If an ocean of the scale modelled by the team existed, it would have profound implications for the thermal and chemical evolution of Uranian satellites. A targeted mission could resolve whether those oceans were transient or long-lived."

Conclusion

The new Icarus study strengthens the possibility that Ariel once harbored a colossal subsurface ocean driven by tidal heating and orbital evolution. While the ocean—if it existed—appears to be a relic of the moon’s past rather than an obviously active present-day reservoir, the findings underscore the scientific value of returning to the Uranus system. Future missions equipped with radar, magnetometers, and precision gravity instruments could confirm the models, map unobserved terrain, and reveal whether Ariel and its neighbors were transient ocean worlds or retain fluid interiors today.

Source: scitechdaily

Leave a Comment