6 Minutes

Scientists at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, in partnership with Roche, have built a miniaturized human liver platform that can model immune-driven drug reactions seen only in certain patients. By combining patient-derived stem cells with their own immune cells, the team recreated a rare but serious type of drug-induced liver injury in the lab — an advance that could reshape how medicines are tested for safety.

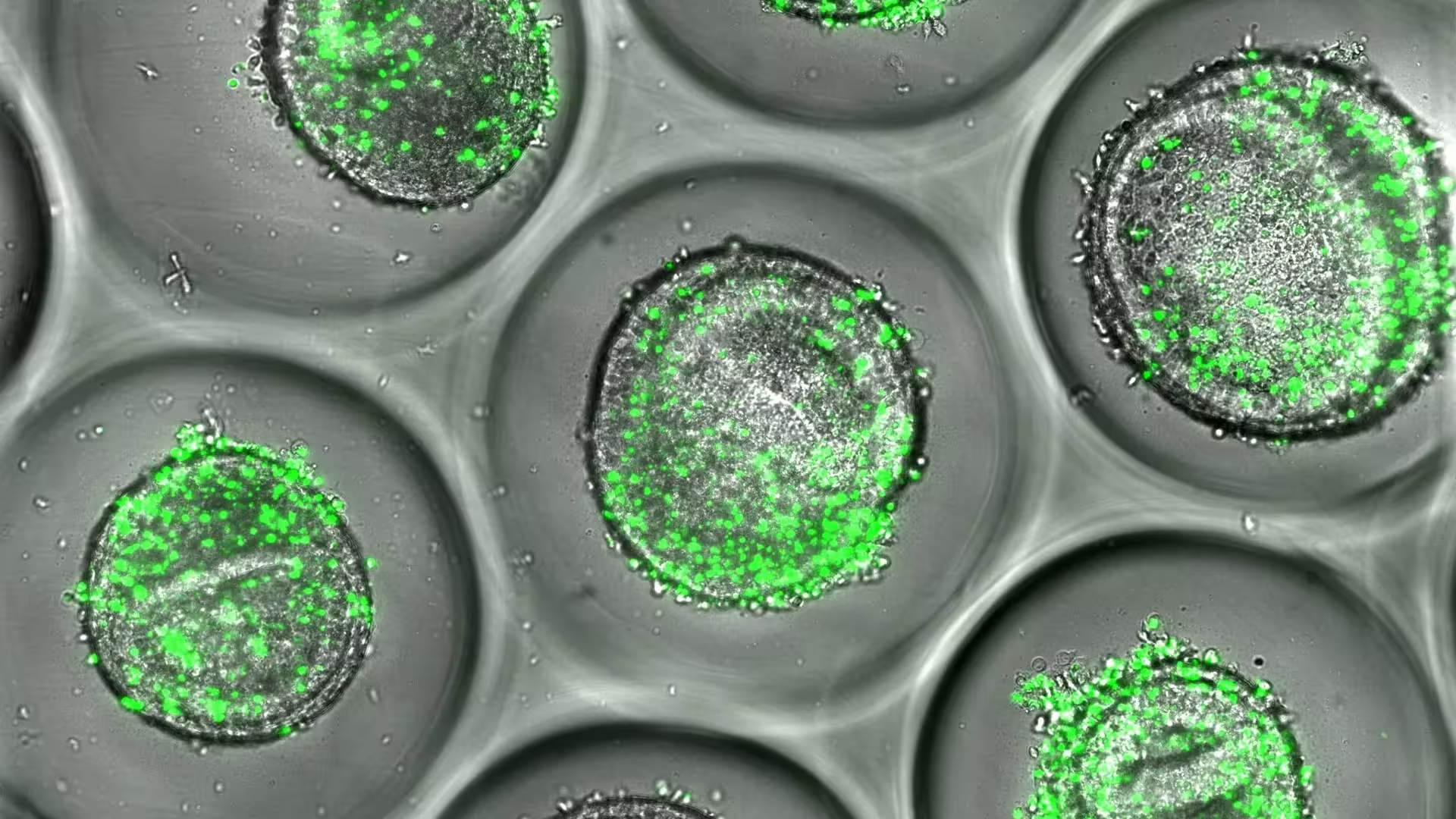

Example of human liver organoids co-cultured with autologous CD8 T cells (green). These tissues can be used during drug development to predict liver toxicity, according to new resaerch published by experts at Cincinnati Children's.

A lab-grown liver that remembers genetics

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a leading cause of acute liver failure and a frequent reason for withdrawing drugs from the market. Most preclinical tests fail to predict rare immune-mediated forms of DILI — called idiosyncratic DILI (iDILI) — because these reactions depend on individual genetics and specific immune responses. The new platform addresses that blind spot by creating an immune-competent, fully human liver model that incorporates a patient’s genetic background.

The system uses induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from donors to grow three-dimensional liver organoids. Those miniature tissues are then paired with the donor’s own CD8+ T cells — the immune cells that can mistakenly attack liver cells if they recognize drug-related molecular patterns. The resulting microarray preserves both genetic and immune individuality, allowing researchers to watch how particular combinations trigger inflammation, cytokine release, and cell damage.

How the organoid microarray reproduces real-world drug harm

As a proof of concept, the team tested flucloxacillin, an antibiotic known to cause liver injury only in people carrying the HLA-B*57:01 gene variant. Traditional models rarely show this effect, but the organoid co-culture generated the hallmarks of immune-mediated liver damage: activation of CD8+ T cells, increased inflammatory signaling, and measurable hepatocyte injury. That close match to clinical observations is what makes the approach promising for predictive toxicology.

Lead authors Fadoua El Abdellaoui Soussi, PhD, and Magdalena Kasendra, PhD, explain that integrating patient-specific immune cells was the missing ingredient for replicating idiosyncratic reactions. Kasendra, director of research and development at the Center for Stem Cell and Organoid Medicine (CuSTOM) at Cincinnati Children’s, stresses that this is about capturing human biology in a scalable, reproducible format that can inform drug development earlier and more reliably.

From method to medicine: the technical breakthroughs

The platform builds on prior organoid innovation by using matrix-free microarray technology and refinements from labs experienced in generating robust liver organoids from iPSCs. That combination enables higher throughput than traditional organoid cultures while keeping the key features of a human immune response. Critical to the effort was collaboration with Roche, which brought translational toxicology expertise and resources to accelerate development and validation.

Beyond reproducing a single gene-drug interaction, the researchers are automating the assays and expanding the donor pool to cover broad genetic diversity. The goal is a screening system that can flag potential immune-mediated toxicity across populations before drugs reach clinical trials. Such capability would cut downstream patient risk and reduce late-stage drug failures.

Implications for patients and drug developers

For patients, the platform points toward a future where safety testing accounts for individual genetic risk. Imagine a scenario in which a drug candidate is screened against a panel of organoid-immune pairs representing thousands of different genetic profiles. Developers could identify vulnerable subgroups early and design trials or companion diagnostics to protect those patients.

For industry, scalable human models that reveal immune-driven toxicity could lower attrition, speed decision-making, and ultimately reduce costs tied to late-stage failures. The work also strengthens regenerative medicine and precision toxicology by linking stem cell science with applied safety testing — an integration that several biotech and instrument partners, including Molecular Devices and Danaher, are already supporting.

Expert Insight

"This represents a pivotal step toward truly predictive toxicology," says Dr. Elena Mora, a clinical pharmacologist at the University of Oxford (comment provided for context). "By modeling how a patient’s immune system interacts with their own liver tissue, researchers can uncover patterns that animal tests or isolated cell cultures miss. It won’t replace clinical trials, but it will make them smarter and safer."

Challenges and the road ahead

Despite the promise, challenges remain. Scaling organoid production while maintaining biological fidelity is nontrivial, and ensuring assays are reproducible across laboratories will require standardization. Additionally, immune-mediated reactions are multifactorial: environmental triggers, co-medications, and chronic conditions may modulate risk beyond genetics and CD8+ T cell behavior. The team acknowledges these limits and is pursuing automation and broader donor sampling to capture more of that complexity.

Published in Advanced Science on Sept. 26, 2025, the study positions Cincinnati Children’s CuSTOM Accelerator as a leader in translating organoid science into practical tools. According to the authors, this effort is an early but significant move toward personalizing drug safety assessments — a change that could prevent harm for the small subset of people vulnerable to immune-mediated liver injury.

As organoid platforms mature, regulators, industry, and clinical researchers will need to work together to validate and adopt these systems into safety pipelines. If successful, the next generation of preclinical testing will be more human, more predictive, and better at protecting patients from rare but severe adverse drug reactions.

Source: sciencedaily

Comments

mechbyte

promising tech, but big gaps: automation, diversity of donors, and external factors. Feels a bit overhyped rn, show cross-lab reproducibility before hype.

labflux

Wow this actually gives me chills. The liver that 'remembers' genetics is wild, if they can scale it and keep fidelity, huge deal. Fingers crossed

Leave a Comment