5 Minutes

Researchers have shown that sound waves can be used to coordinate fleets of tiny robots that behave like living collectives: they move in unison, adapt their shape to tight spaces, and even recover from damage. The discovery—led by a Penn State team and published in Physical Review X—opens new paths for microrobotics in medicine, environmental cleanup, and beyond.

A new study led by Penn State researchers shows for the first time how sound waves could function as a means of controlling micro-sized robots.

Why acoustic signals matter for swarm robotics

Biological groups—from bats using echolocation to insects swarming—often rely on sound to navigate and coordinate. Inspired by nature, the research team modeled microrobots that emit and detect acoustic signals to maintain cohesion and steer as a group. Acoustic communication stands out because sound travels quickly and with relatively little attenuation compared with chemical cues, making it an efficient channel for coordination among distributed, simple devices.

In the Penn State simulations, each agent had a minimal hardware profile: a motor to move, a tiny microphone and speaker for sound exchange, and an oscillator to tune movement relative to the acoustic field. Despite this simplicity, the ensemble produced complex, emergent behaviors—shifting shape, converging on strong signals, and re-forming after disruption—behaviors normally associated with more sophisticated control systems.

How the simulation worked: a peek under the hood

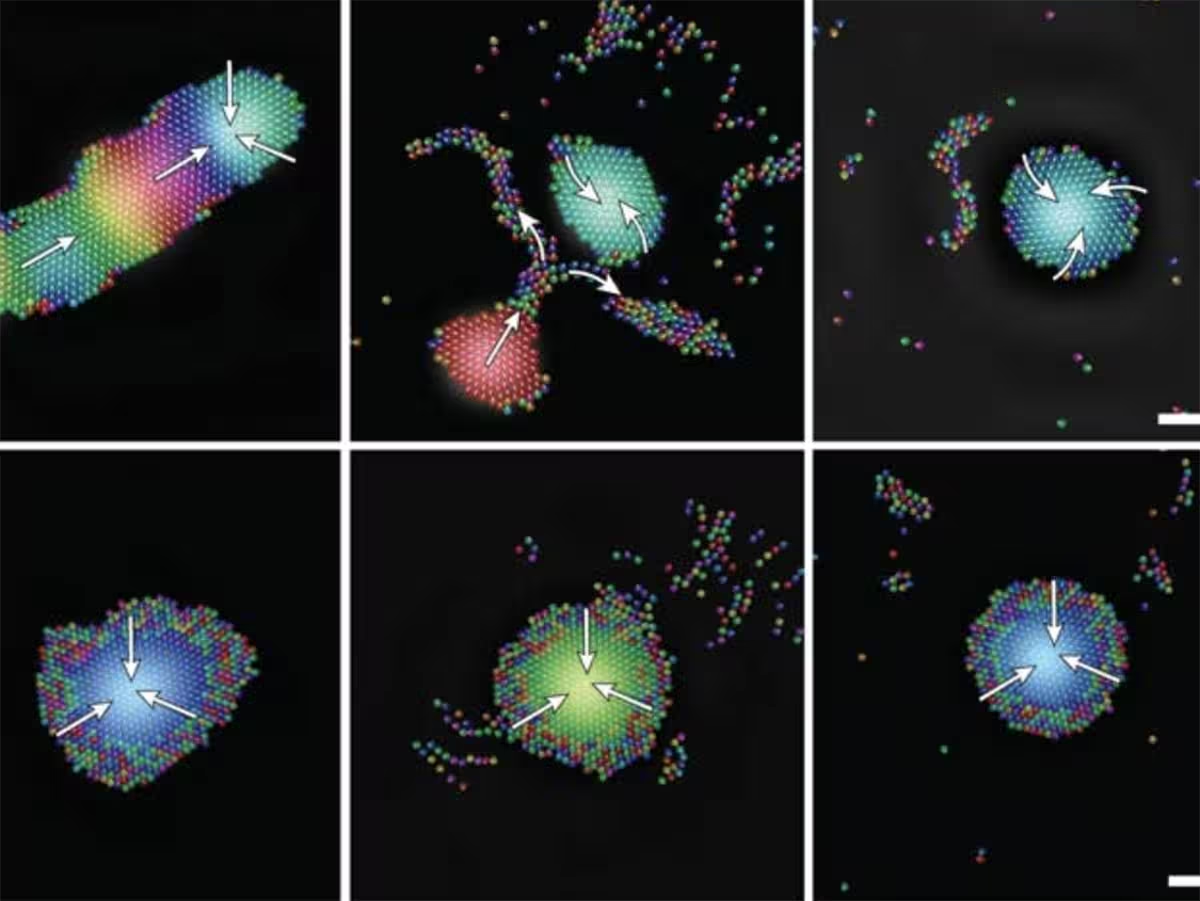

The team used an agent-based computer model to track thousands of tiny, self-propelled units. Each simulated microrobot emitted a periodic acoustic signal and measured the local acoustic field created by its neighbors. By synchronizing its internal oscillator to the dominant local frequency and migrating toward the strongest acoustic source, the aggregate of very simple units self-organized into coherent swarms.

Because the model operates on general physical principles rather than a bespoke codebase, the researchers argue that experimental implementations with similar acoustic and mechanical properties should reproduce the core phenomena. In short: collective intelligence emerged from humble building blocks—no centralized controller, no detailed map of the environment, just local sound-based feedback.

Potential missions: from inside the body to contaminated rivers

What makes these sound-guided microrobots especially compelling is their adaptability. In simulations the swarms snaked through confined corridors, reassembled when split apart, and maintained functionality after partial loss of units. That kind of resilience could be a game-changer for applications including:

- Targeted drug delivery: fleets of microrobots could navigate vascular channels to concentrate medication at specific tissues while avoiding healthy areas.

- Environmental remediation: dispersed microrobots might locate and neutralize pollutants in complex terrains such as sediment layers or clogged pipes.

- Search and rescue and inspection: small acoustic swarms could explore collapsed structures or tight industrial spaces where humans and larger robots cannot go.

Scientific context: active matter and emergent intelligence

The findings feed into a growing field called active matter, which studies how many self-driven units—whether cells, bacteria, or synthetic particles—produce large-scale patterns and functions. Historically, researchers have relied on chemical signaling to program interactions in active matter. Demonstrating acoustic control expands the toolkit: sound propagates farther and faster, and acoustic hardware can be extremely simple and energy-efficient at small scales.

According to the study lead, Igor Aronson, this approach could yield microrobots that are both smarter and more robust while retaining minimal internal complexity. Instead of packing each unit with processors and sensors, designers may exploit physics—acoustic fields and synchronization—to achieve coordinated behaviors at scale.

Challenges before real-world devices

Translation from simulation to laboratory and field devices requires solving practical problems: engineering emitters and microphones that work reliably at micro scales, ensuring safe acoustic levels for biological tissues, and developing materials and propulsion methods that function where chemical gradients or turbulent flows are present. Researchers will also need to address control in heterogeneous environments and prevent unwanted interference between multiple swarms operating nearby.

Expert Insight

Dr. Maya Patel, a robotics engineer specializing in swarm systems, notes: "The real elegance of acoustic coordination is simplicity. You don't need heavy computation on each node—just the right coupling between emission, detection, and motion. That said, making tiny transducers that are durable and energy efficient is the next big challenge. If we solve that, the range of applications—from targeted therapeutics to environmental sensing—becomes enormous."

What comes next

Future work will likely combine experiments with progressively smaller acoustic components and more realistic environmental models. Cross-disciplinary teams—linking physicists, engineers, biologists, and materials scientists—are needed to build prototypes and test performance in relevant settings. If acoustic swarms can be realized physically as they appear in the simulations, they could represent a practical, low-complexity route to smart microrobots that act collectively to solve tasks beyond the reach of single devices.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

bioNix

Cool idea, but can they really make mics that small and power them? noise in real environments gonna wreck this, right?

mechbyte

whoa, tiny robots syncing by sound? wild. imagine them slithering through veins, fixing stuff, but what about safety, tissue damage? sounds promising tho

Leave a Comment