4 Minutes

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst report a nanoparticle vaccine that prevented multiple tumor types in mice for the full 250-day study period. The experimental formulation combines cancer-specific antigens with a potent 'super' adjuvant to train the immune system to spot and destroy tumor cells before they can take hold.

How the vaccine trains the immune system

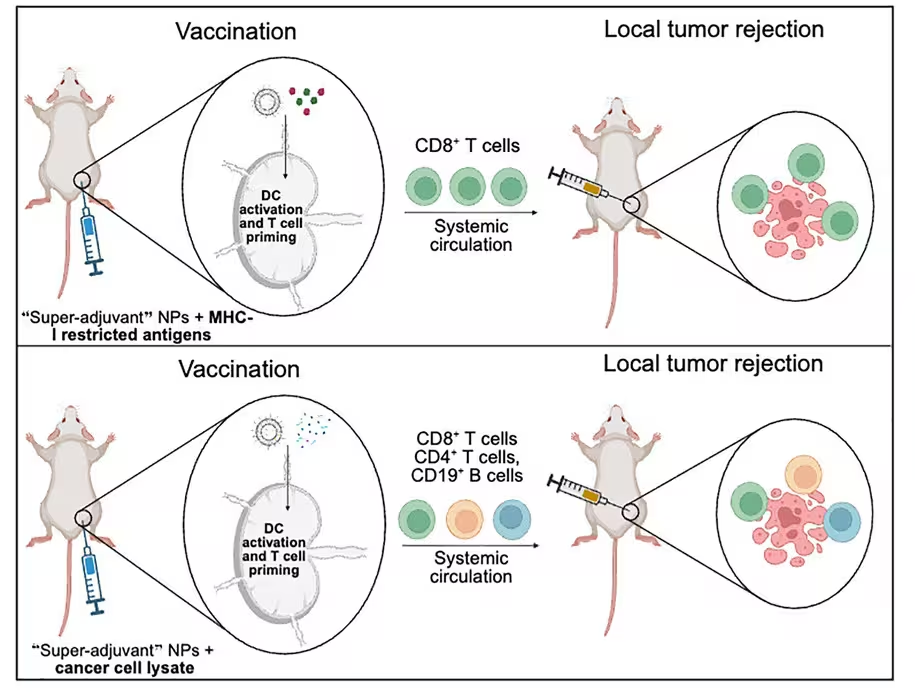

The vaccine uses lipid nanoparticles to present a recognizable portion of cancer cells as an antigen, a molecular label that flags a threat to immune cells. Encapsulated alongside these antigens is a so-called super adjuvant: two immune stimulants delivered together inside nanoparticles to boost the breadth and strength of the immune response. In essence, the formulation acts like a training program, teaching immune cells to recognize cancer signatures and attack emerging tumors.

Why nanoparticles?

Nanoparticles are tiny delivery vehicles that protect fragile molecules, control release, and direct components to the same immune cells at the same time. By packaging antigens and adjuvants together, the vaccine engages multiple immune pathways simultaneously, producing a more coordinated and durable reaction than many single-component formulations.

Results: survival, cross-protection and durability

In the first set of experiments researchers loaded nanoparticles with melanoma-specific peptides and vaccinated mice before exposing them to melanoma cells weeks later. The outcome was striking: 80 percent of vaccinated mice survived and remained tumor-free over 250 days, while non-vaccinated controls and animals given alternative formulations all developed tumors and died within seven weeks.

To test broader protection, the team switched to a general antigen called tumor lysate, which is made from broken-up cancer cells and carries a mix of tumor proteins. Mice vaccinated with the lysate formulation were challenged with three cancer types: melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and triple-negative breast cancer. Protection rates varied by tumor type but were substantial: 88 percent tumor-free for the pancreatic model, 75 percent for triple-negative breast cancer, and 69 percent for melanoma.

A graphical abstract of how the cancer vaccine works. (Kane et al., Cell Rep. Med. 2025)

In follow-up tests the team attempted to mimic tumor spread and found that every surviving animal remained tumor-free, suggesting a durable immune memory effect. 'By engineering these nanoparticles to activate the immune system via multi-pathway activation that combines with cancer-specific antigens, we can prevent tumor growth with remarkable survival rates,' says Prabhani Atukorale, biomedical engineer at UMass Amherst.

Implications, limits and next steps

These results, published in Cell Reports Medicine, point to a flexible platform that could be adapted to target different cancers or used prophylactically in high-risk patients. Using tumor lysate hints at a near-universal approach where a single vaccine primes immunity against a spectrum of tumor antigens rather than one mutation or peptide.

However, the authors emphasize a major caveat: these experiments were performed in mice. Animal models are invaluable for early-stage testing but do not guarantee safety or efficacy in humans. Before any clinical application, the vaccine will require extensive preclinical safety profiling, optimization of dosing and adjuvant balance, and carefully designed human trials to assess immune response, toxicity, and real-world protection.

- Scientific context: nanoparticle delivery and multi-adjuvant strategies are a growing trend in immunotherapy.

- Key discovery: strong, durable tumor prevention in multiple mouse cancer models for 250 days.

- Next steps: safety testing, formulation tuning, and eventual human trials if preclinical work supports translation.

The research expands on efforts to create vaccines that not only treat but prevent cancer, offering a potential roadmap for future immunopreventive strategies in oncology.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment