8 Minutes

If you were born between 1981 and 1995, you may have noticed something unsettling: friends, colleagues or peers being diagnosed with illnesses that once guardedly belonged to later life. Early-onset cancers, metabolic conditions and chronic gut complaints are no longer edge cases. Scientists now warn that lifestyle patterns characteristic of millennials are shifting the cancer burden to younger ages — but practical changes can reduce risk.

A generational shift in cancer risk

Global data show a sharp rise in early-onset cancer. Between 1990 and 2019, cancers diagnosed in people under 50 climbed by roughly 79% worldwide while mortality in that group rose about 28%. These aren’t small fluctuations: they represent a genuine epidemiological shift. Why is this happening now?

About 80% of cancers are considered sporadic, meaning they arise primarily from environmental and lifestyle exposures rather than inherited mutations. That phrase — environmental and lifestyle — covers what we eat, how much we move, sleep patterns, alcohol use, chronic stress, exposure to pollutants, and medication habits. In short: the daily context in which we live matters a lot, and for millennials that context looks very different from the lives of our parents.

Diet, childhood obesity and the gut microbiome

One of the strongest drivers behind rising early-onset cancer is diet. Childhood obesity began climbing in the 1980s and has continued. The World Health Organization estimates that in 2022 more than 390 million children and adolescents aged 5 to 19 were overweight, with roughly 160 million classified as obese. These are not cosmetic labels: excess weight in early life is linked to insulin resistance, chronic low-grade inflammation and hormonal imbalances that increase risk for colorectal, breast and endometrial cancers.

Crucially, high body mass index (BMI) in childhood leaves a long shadow. A meta-analysis covering more than 4.7 million people found that individuals with elevated BMI in early life face a markedly higher risk of colorectal cancer in adulthood — roughly 39% higher for men and 19% higher for women compared with those who maintained a healthy BMI as children.

What we eat also changes the gut microbiome. Diets heavy in ultra-processed foods reduce bacterial diversity and can favor strains that produce pro-inflammatory metabolites. The result is a gut ecosystem that promotes irritation, impaired barrier function and diseases that range from irritable bowel syndrome to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Ask a room of thirty-somethings how many struggle with chronic digestive symptoms and few hands will be left down.

Alcohol, hidden chemicals and patterns of drinking

Social life and alcohol are tightly intertwined for many millennials. For decades there was a narrative that modest wine consumption could be protective, but current evidence is clear: there is no safe level of alcohol. The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies ethanol as a Group 1 carcinogen, the same category as tobacco. The body converts ethanol into acetaldehyde, which damages DNA and interferes with repair.

Drinking patterns matter too. While older generations may drink more frequently, millennials often binge — fewer drinking days, but heavier intake on those days — a pattern linked to higher risks for several cancers and other harms. Adding to the concern, a study published in Environmental Science & Technology reported that many beers contain trace levels of perfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS — persistent 'forever chemicals' associated with elevated risks of testicular and kidney cancers.

Socialising for millennials tends to involve alcohol and food. (FoxysGraphic/Canva)

Sleep loss, circadian disruption and DNA repair

Sleep patterns have shifted dramatically with the rise of screens, shift work and a 24/7 online culture. Surveys indicate millennials and Gen Z get on average 30 to 45 minutes less sleep per night than baby boomers. Artificial light at night suppresses melatonin, a hormone that acts as an antioxidant, regulates circadian rhythms and plays a role in the timing of cell division.

Chronic short sleep and circadian disruption blunt DNA repair mechanisms and reduce melatonin’s protective effects. When repair processes falter and cell cycle timing becomes erratic, mutations accumulate and the probability that a damaged cell evolves toward malignancy increases. In other words, poor sleep is not merely an irritant — it is a biological stressor that compounds other risks.

Stress, immunity and the physiology of chronic worry

Millennials report high rates of anxiety and chronic stress. Biologically, persistent elevation of cortisol and related stress mediators promotes insulin resistance, raises blood pressure and suppresses immune surveillance — the immune system's ability to spot and remove abnormal cells. Studies linking chronic stress to cancer outcomes suggest higher stress is associated with worse survival, and some analyses report up to double the mortality risk among those with poorly managed chronic stress.

Stress also fuels inflammation, which in turn creates an environment conducive to cancer initiation and progression. Stress reduction is therefore not just about mental wellbeing; it is a measurable factor in cancer prevention strategy.

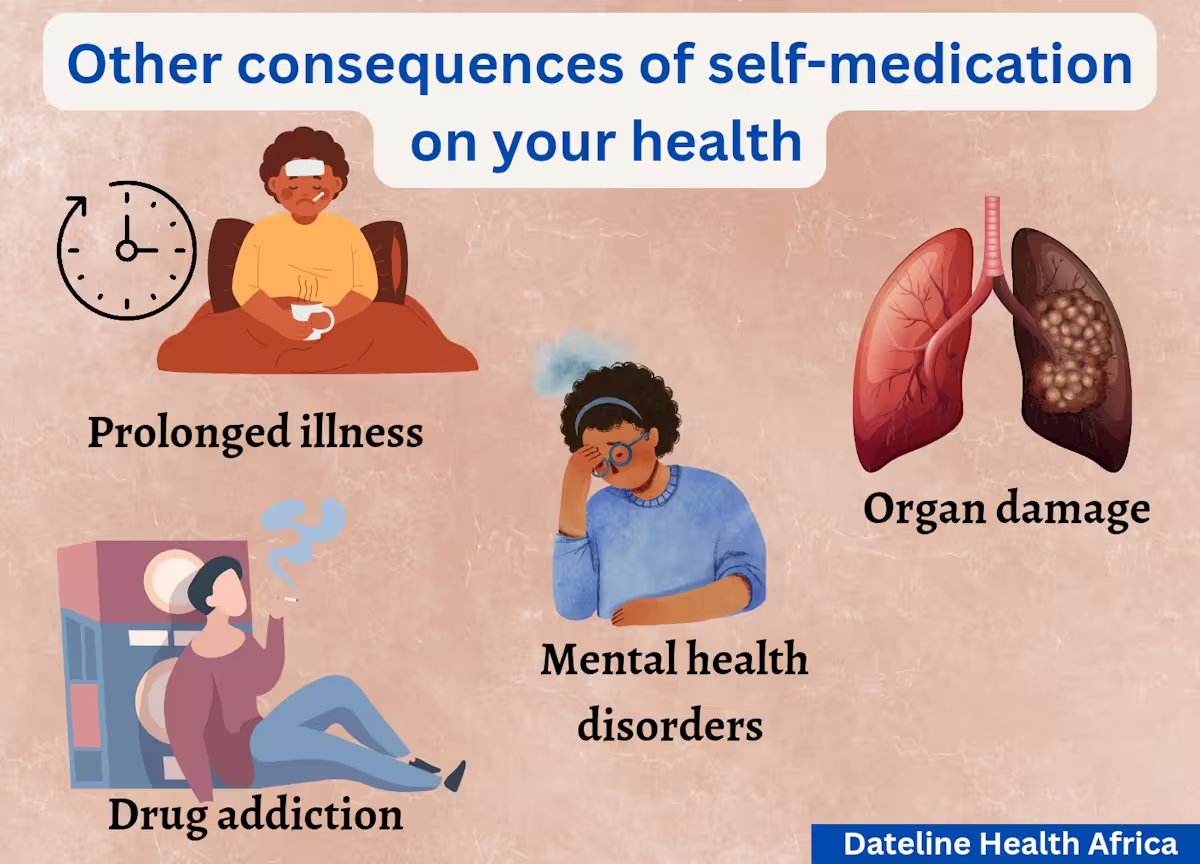

Medication habits and unintended harms

Younger generations are more likely to self-medicate, use long-term pharmaceuticals for symptom control, or rely on quick fixes rather than prevention. That brings risks. High or prolonged paracetamol use can damage the liver and may be associated with a higher risk of liver cancer in susceptible populations. Extended use of some oral contraceptives slightly increases breast and cervical cancer risk, even as they lower the risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers — a trade-off that should be discussed with a clinician.

Frequent antacid or antibiotic use can alter the stomach and gut environment, potentially creating conditions that promote carcinogenic processes through changes in microbiota or exposure to harmful compounds. These are nuanced effects, but they add up at population scale.

Additional consequences of self-medication. (Dateline Health Africa)

What the near future looks like

Projections are concerning. Global cancer cases are expected to climb from about 20 million in 2022 to nearly 35 million by 2050 — an increase close to 77%. The rise is most pronounced for digestive and gynecological cancers in younger adults, mirroring trends in obesity, diet, alcohol and reproductive patterns.

This trajectory is not destiny. Many of the drivers behind these trends are modifiable. Public health measures, improved food environments, policies limiting harmful chemical exposure, alcohol harm reduction, better sleep hygiene and accessible mental health care can blunt the rise in early-onset cancers. On an individual level, targeted lifestyle changes produce measurable benefits.

Expert Insight

Dr. Elena Torres, an epidemiologist specializing in lifestyle-related cancer, notes: 'We are seeing the biological consequences of social change. The good news is that most of these risks are preventable. Reducing childhood obesity, curbing binge drinking, improving sleep and addressing environmental exposures will lower cancer incidence. Prevention policies must be as ambitious as the treatments we’re developing.'

Practical steps for risk reduction

Diet and weight

- Prioritize whole foods, vegetables, fiber and limited ultra-processed products.

- Support childhood nutrition and physical activity to prevent lifelong metabolic risk.

Alcohol and chemicals

- Recognize there is no safe threshold for alcohol in terms of cancer risk; reduce intake and avoid binge episodes.

- Advocate for transparency and regulation around PFAS and similar contaminants.

Sleep, stress and medications

- Prioritize consistent sleep timing, limit late-night screens and treat sleep disorders.

- Integrate stress-management strategies, from therapy to mindfulness and community support.

- Use medications judiciously and consult clinicians about long-term prescriptions and contraceptive choices.

Millennials are not powerless. Small, sustained changes across diet, sleep, stress and chemical exposure can shift future risk profiles. Society-level policies and clinical guidance must follow the evidence to protect younger generations. The rise in early-onset cancers is a public-health alarm; how we respond now will shape decades to come.

Source: sciencealert

Comments

max_x

I've seen this in clinic, young ppl with chronic gut pain and odd symptoms. sleep loss + booze, yep. if we taught healthy habits early maybe fewer cancers later

labcore

Is the rise real or partly due to better detection/screening? also confounders like diagnostics and reporting changes… curious about raw age adjusted rates tho

datapulse

wow this is terrifying… friends my age getting cancers? makes late nights, beers and junk food feel reckless. need policy change not just willpower

Leave a Comment