4 Minutes

Greenland's solid ground is not as solid as it looks. Decades of ice build-up, melting, and a deep-time rebound from the last Ice Age are subtly bending and stretching the island, nudging it northwest by a few centimeters each year. The changes are small in human terms, but they matter for navigation, mapping, and our understanding of how Earth's surface responds to rapid climate change.

Precision tracking: how scientists measured Greenland's slow drift

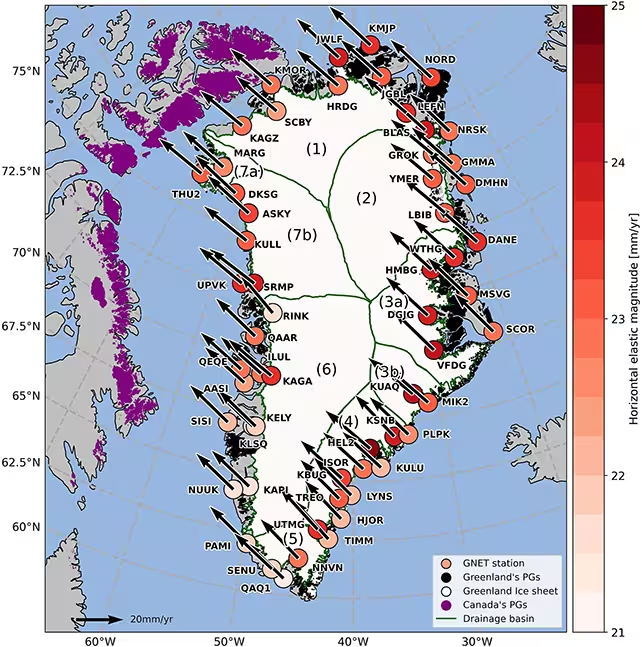

An international research team led by the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) combined two decades of GPS observations from 58 stations across Greenland with thousands of additional GPS records from North America and computer models that simulate crustal motion over the past 26,000 years. This multi-layered approach let them separate three overlapping drivers of motion: tectonic plate forces, contemporary unloading from recent ice melt, and the long-term Glacial Isostatic Adjustment (GIA) still playing out since the end of the last Ice Age.

Results published in Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth show Greenland is moving northwest at roughly 2 centimeters (0.79 inches) per year. Locally, some coastal areas are expanding while other regions contract and rise. By isolating horizontal movement — often harder to quantify than vertical uplift — the study provides the most precise map yet of how Greenland's shape is slowly changing.

Why the island is twisting: three forces at work

The first factor is simple plate tectonics: Greenland rides on the North American plate, which exerts broad-scale forces over geological time. Superimposed on that is the immediate response to recent ice loss. As glaciers thin and retreat, the pressure on the bedrock eases; the crust rebounds and moves outward in places.

The third and most persistent influence is Glacial Isostatic Adjustment (GIA). This is the long-term viscous rebound of Earth’s mantle after the massive ice sheets of the last Ice Age depressed the crust. GIA produces uplift and horizontal motions that continue thousands of years after the ice has gone.

"Overall, this means Greenland is becoming slightly smaller, but that could change in the future with the accelerating melt we're seeing now," says Danjal Longfors Berg, a geophysicist at DTU. In plain terms: recent decades of melting have pushed some parts of the island outward and upward, yet deeper-time processes from prehistoric ice loss are still pulling other areas in the opposite direction.

Greenland is moving to the northwest. (Berg et al., J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth, 2025)

What this means for navigation, climate science and hazards

Surveying and navigation rely on stable reference points. If benchmarks and coastal markers creep by centimeters each year, nautical charts, positioning systems, and local infrastructure planning all need regular updates. For climate scientists, accurate models of crustal motion are essential to untangle local sea-level change from global trends.

There are wider geophysical consequences too. As ice is removed, the crust and upper mantle respond — a process that has been linked in past studies to increased seismicity, the potential reawakening of volcanic systems, and ecological shifts that could enhance greenhouse-gas release from newly exposed soils. The authors stress continued monitoring: ongoing GPS measurements and refined models will sharpen predictions of how Greenland—and the planet—adjusts as high-latitude ice continues to decline.

"It's important to track these shifts, not just for geoscience, but for practical reasons like mapping and maritime safety," Berg adds. The new dataset gives scientists and policymakers a better foundation to anticipate changes in a rapidly warming Arctic.

Source: sciencealert

Leave a Comment