8 Minutes

For the first time, astronomers have used a cutting-edge optical device called a photonic lantern on a ground-based telescope to produce an unprecedentedly sharp image of a star’s surrounding disk. Led by UCLA researchers using the Subaru Telescope on Maunakea, the team combined advanced photonics, adaptive optics and new data-processing tricks to resolve structural details never seen before — including an unexpected lopsidedness in the hydrogen disk around the star β Canis Minoris (β CMi).

The result is not just a prettier picture. It is a demonstration that small, clever hardware changes and smarter analysis can push single telescopes toward performance previously reserved for large telescope arrays or interferometers. That matters because resolving tiny, distant structures — from protoplanetary disks to stellar winds — is central to answering how planets and stars form and evolve.

How a photonic lantern re-engineers starlight

Traditional imaging collects light at a telescope’s focus and forms a direct image on a detector. The sharpness you get is fundamentally limited by the telescope aperture and the wave nature of light — the so-called diffraction limit — and by turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere. For decades, astronomers have improved angular resolution by building larger mirrors or by linking telescopes into interferometric arrays. The photonic lantern offers a different route.

A photonic lantern is an optical fiber device that takes the complex incoming light field and splits it into multiple channels according to the wavefront’s spatial structure. Think of it like separating a musical chord into its individual notes: subtle phase and amplitude patterns that would blur together in a conventional image become distinct channels to be measured precisely. The lantern also disperses the light by wavelength, enabling the team to track tiny wavelength-dependent shifts in the apparent position of the source.

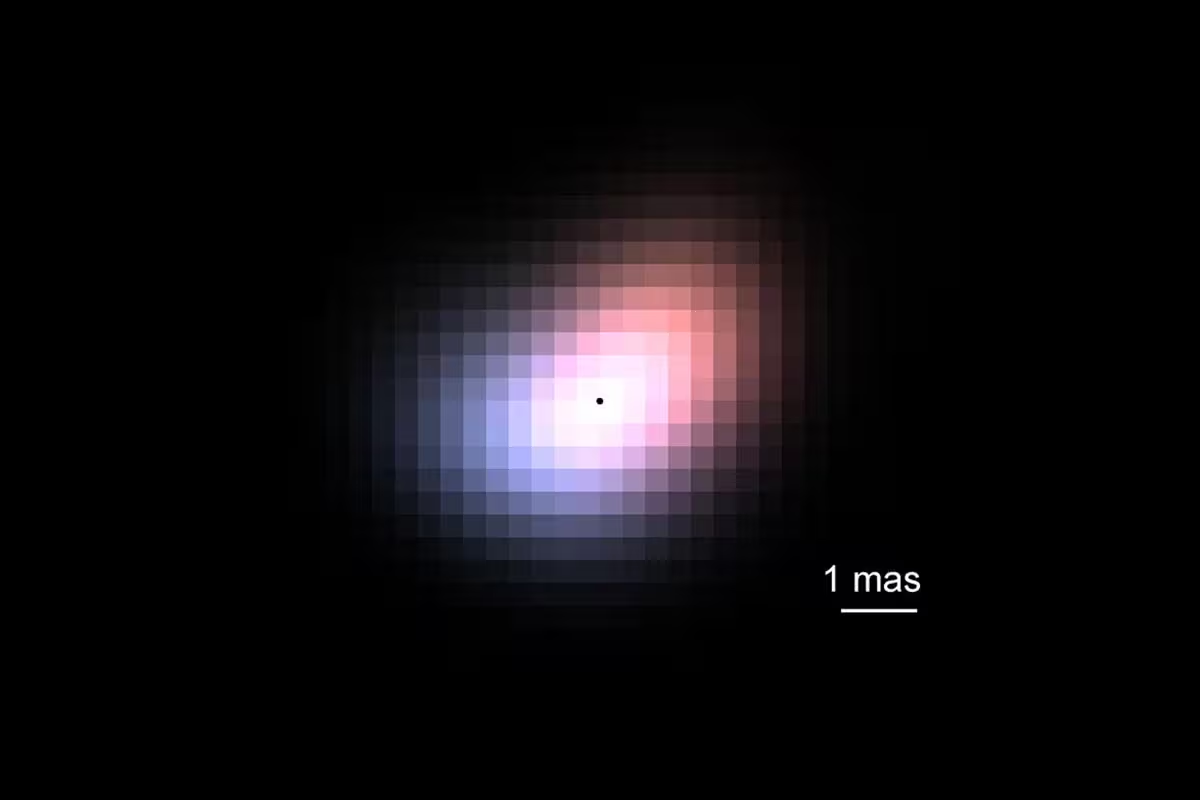

Reconstructed image of the compact, fast-rotating asymmetric disc around β CMi. The white scale bar at the bottom right marks 1 milliarcsecond — equivalent to a 6 feet scale at the distance of the moon. Credit: Yoo Jung Kim/UCLA

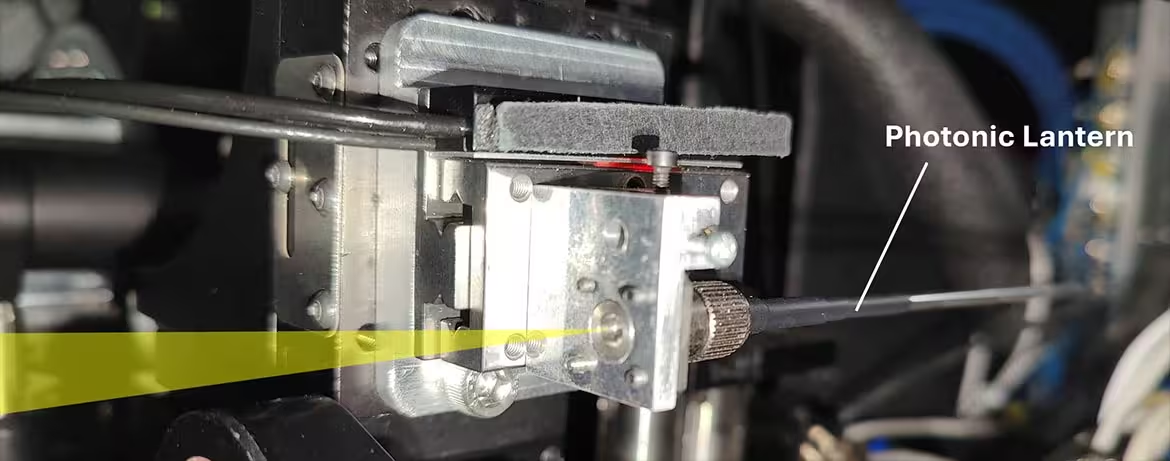

In practice the photonic lantern was installed as part of a novel instrument called FIRST-PL, developed through international collaboration led by the Paris Observatory and the University of Hawai‘i, with design and manufacturing contributions from the University of Sydney and the University of Central Florida. The unit sits downstream of the Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme Adaptive Optics (SCExAO) system to receive a stabilized beam of starlight before the lantern separates it into channels for precise measurement.

Beating the diffraction limit — not by brute force

“For any telescope of a given size, the wave nature of light limits the fineness of the detail that you can observe with traditional imaging cameras. This is called the diffraction limit,” explains Michael Fitzgerald, a UCLA professor of physics and astronomy involved in the project. “Our team has been working to use a photonic lantern to advance what is achievable at this frontier.”

To reach beyond standard limits, the team relied on three coupled advances: extremely stable adaptive optics to correct fast atmospheric distortions, a photonic lantern to preserve and sort subtle wavefront signals, and new computational methods to extract spatial information from the multi-channel outputs. The combined approach allowed measurements of wavelength-dependent image shifts at roughly five times the precision previously possible with similar setups.

Photo of the photonic lantern mounted on the FIRST-PL instrument at the Subaru Telescope. The yellow triangle indicates the path of the light entering the lantern. Credit: Sébastien Vievard/University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa

Those wavelength-dependent shifts are critical because β CMi’s disk exhibits Doppler-shifted emission: gas moving toward Earth appears bluer, while gas moving away is redder. By measuring how the apparent position of the emission changes with color, the researchers could map rotational motion and directly resolve structures on scales of milliarcseconds — at the distance of β CMi, equivalent to a few astronomical units or less.

A surprising lopsided disk and what it implies

The Subaru observations confirmed that the hydrogen-rich disk around β CMi is compact and rotating rapidly, but they also revealed an asymmetry — a measurable lopsidedness in the disk’s brightness and structure. “We were not expecting to detect an asymmetry like this, and it will be a task for the astrophysicists modeling these systems to explain its presence,” said Yoo Jung Kim, the UCLA doctoral candidate and first author on the Astrophysical Journal Letters paper describing the result.

Disk asymmetries can point to several physical causes: a nearby or embedded companion (a planet or stellar partner) gravitationally perturbing the gas, one-armed oscillations in the disk, localized heating or density enhancements, or even dynamic flows driven by rapid stellar rotation. Any of these mechanisms would feed into models of disk evolution, angular momentum transport and potential planet formation in such environments.

Sébastien Vievard climbing on the SCExAO instrument, in which the photonic lantern is installed, to check the point where light enters the device to ensure that the optical elements are in the correct position. Credit: Sébastien Vievard/University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa

Technical hurdles: atmosphere, stability and data

Even with extreme adaptive optics, the photonic lantern proved sensitive to residual atmospheric fluctuations. Yoo Jung Kim developed new data-processing filters to remove remaining turbulence signatures and recover the spatial signals encoded in the lantern channels. That blend of instrumentation and algorithmic innovation is a recurring theme: photonic devices expand what can be captured, but software must evolve to interpret the richer data stream.

Nemanja Jovanovic, a study co-leader at Caltech, highlighted the potential: “This work demonstrates the potential of photonic technologies to enable new kinds of measurement in astronomy. We are just getting started. The possibilities are truly exciting.”

Why this matters for the future of high-resolution astronomy

- Smaller telescopes can gain access to higher effective resolution without building larger apertures or long-baseline interferometers, lowering cost and complexity for certain science cases.

- Photonics-based instruments are highly scalable: similar lantern-based concepts can be adapted for interferometry, spectrographs, or for feeding multiple science instruments simultaneously.

- Measurements sensitive to subtle wavelength-dependent shifts open new diagnostics for kinematics in disks, stellar surface features, and for detecting faint companions near bright stars.

The full experiment — from the hardware design to the data pipelines — was showcased on the Subaru Telescope and documented in Astrophysical Journal Letters. The approach will likely be tested on other targets and instruments, and could inform design choices for next-generation facilities and upgrades to adaptive-optics-fed spectrographs.

Expert Insight

“This experiment shows how photonics can act as a force multiplier for existing telescopes,” says Dr. Amina Patel, an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute (comment provided for context). “By translating spatial structure into measurable channelized signals, photonic lanterns let us extract information that would otherwise be smeared out. That’s especially important for studying dynamic, small-scale features in disks and for finding faint companions close to bright stars. The technique won’t replace larger apertures or interferometers, but it gives us a powerful new tool to apply where sensitivity and stability permit.”

Looking ahead, astronomers expect to combine photonic lanterns with larger telescopes, deploy improved lantern designs with more channels and broader wavelength coverage, and refine processing algorithms to cope with realistic noise and systematics. As these elements mature, the approach could contribute to high-contrast imaging of exoplanets, detailed maps of young stellar disks, and new ways of doing precision astrometry with single telescopes.

Source: scitechdaily

Comments

max_x

Nice tech demo, but feels overhyped. Need more targets, repeatability and longer runs before calling it a game changer.

astroNix

hold up, how robust is that asymmetry detection vs residual turbulence? seems impressive but could systematics mimic a lopsided disk?

lightmesh

Whoa, photonic lanterns actually giving milliaracsecond detail? Mind blown. If small tweaks can do this, telescopes gonna get wild. Curious about limits...

Leave a Comment